It has been just a little over ten years since President Ali Abdullah Saleh (1990-2012) – following a year of popular demonstrations linked to regional Arab uprisings – decided to resign, thereby propelling Yemen into a decade of instability.

- The conflict between the Houthi rebel movement and forces loyal to the internationally recognised government of President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi (2012-) is reverting to a stalemate in which neither side is likely to prevail militarily over the coming months.

- Hostilities will continue over the coming year and pose significant security risks to organisations with assets, operations and personnel in Yemen. Threats will also stem from terrorism and unrest.

- Houthi cross-border attacks against Saudi Arabia will remain frequent over the coming year. Attacks against the UAE remain credible, though the likelihood is decreasing.

- Further international sanctions against the Houthis will likely be introduced in the coming months, which would further raise the cost of operating in Yemen for businesses and humanitarian organisations.

The conflict

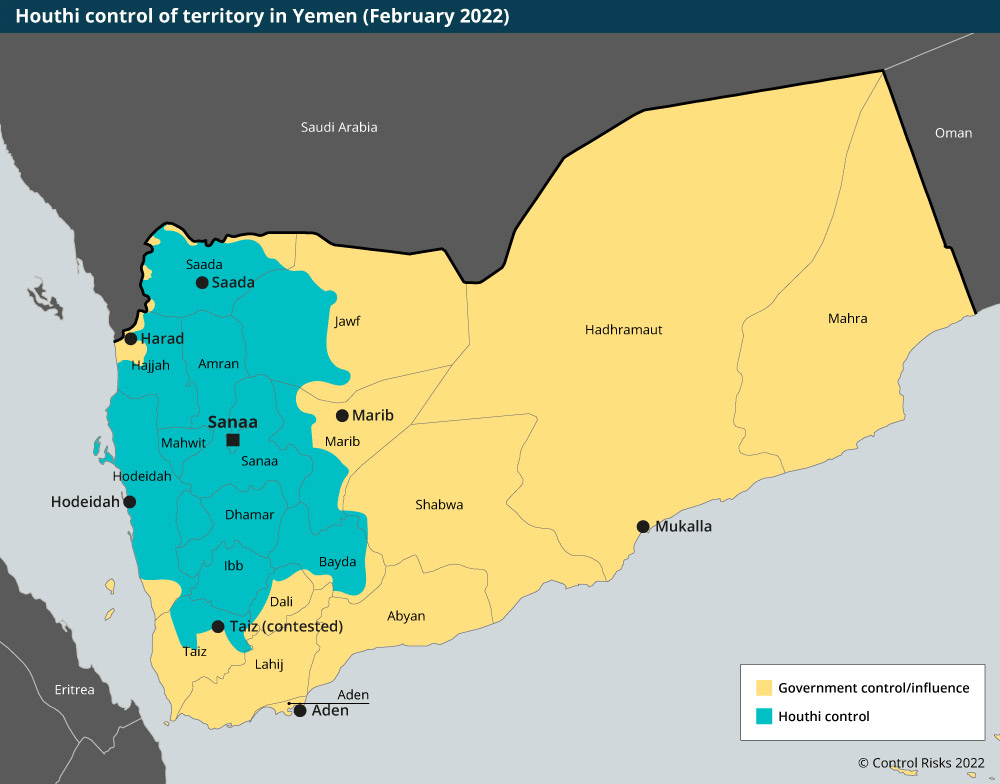

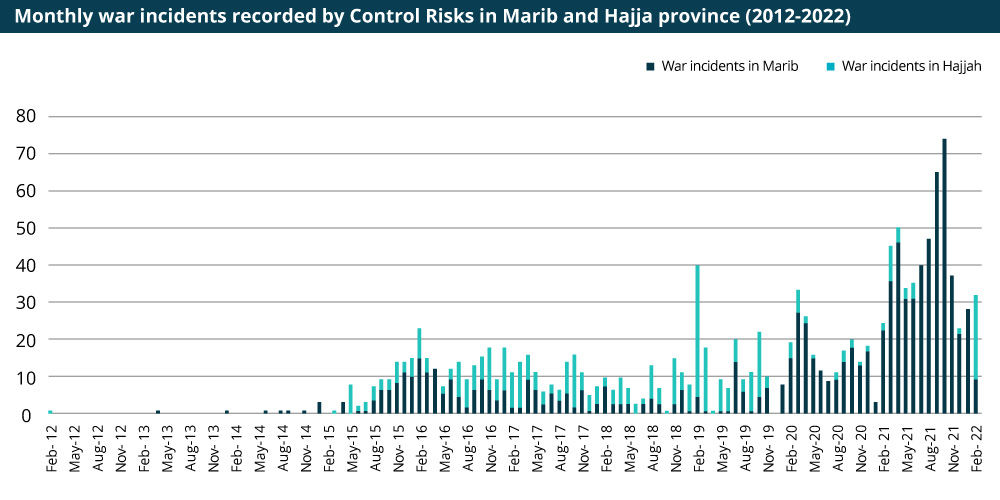

The past year has seen a marked intensification of fighting between the Houthis and forces affiliated with the internationally recognised government of President Hadi. In February 2021, the Houthis launched an offensive on oil-rich Marib province, the last government stronghold in northern Yemen. The rebels calculated that if they could seize the province’s eponymous capital, they would secure new resources, significantly strengthen their negotiating position in any future peace negotiations, and significantly consolidate their military position on the eastern boundary of their territory.

In late 2021, as the rebels appeared increasingly likely to march on Marib city and capture the province’s oil fields, the UAE-backed and -trained Giants Brigades were deployed to neighbouring Shabwa province. In early January, the outfit started rolling back Houthi advances and began liberating parts of southern Marib province in a bid to reopen transport links between government-affiliated military bases in Shabwa and government-controlled Marib city. The brigade’s push officially lasted until 28 January, when it announced it was withdrawing from the frontline. The withdrawal was undoubtedly commanded by the UAE, which sought to avoid further cross-border attacks against its capital after the Houthis targeted the Gulf Arab state on 17, 24 and 31 January.

Back to stalemate

Since the withdrawal of the Giants Brigades from the frontline in Marib, pro-government forces’ operations to retake territory have slowed. In February, the Saudi-backed forces affiliated with the government – which are less effective than the UAE-backed forces – have only succeeded in capturing a handful of new locations beyond Marib province’s Harib city. (The Giants Brigades reportedly originally recaptured Harib city in mid-January.) Although intense clashes in 2021 and early 2022 significantly depleted Houthi ranks, the rebel movement will continue its single-mindedly aim to hold all of Marib province, a key prize in the conflict.

In an attempt to spread the Houthis’ resources thinner, Saudi-backed pro-government forces simultaneously opened a new front in Yemen’s northwest. On 5 February, these forces launched an offensive against Houthi-controlled Harad city (Hajja province), but the effort is unlikely to alter the balance of power, as the Houthis appear to be effectively defending the city so far. Despite small frontline movements in Hajja and Marib, the conflict has largely reverted to the status quo from before the Giants Brigades’ intervention in January. Neither side is likely to prevail militarily in the coming months, and peace negotiations are still a long way away.

Security risk

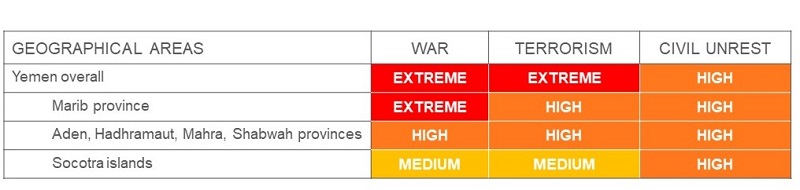

With no imminent prospects for peace talks, hostilities in Yemen will continue to pose security risks to businesses with assets, operations or personnel in the country. Oil and gas operations in Marib province will continue to face the greatest threat due to military operations there. In Shabwa province, the risk of disruption to oil and gas operations remains but has decreased since January, when the Houthis were rolled back from the province. In Hadhramaut province, oil operations will remain largely unaffected by the conflict, as hostilities are taking place 311 miles (500km) from the province’s main oil fields. Nonetheless, in January, one of the last international oil companies operating in Yemen announced it was suspending operations at facilities in Hadhramaut in light of the overall degradation of the security environment in Yemen over the past year.

Organisations in Yemen will also continue to face significant security threats that do not necessarily stem directly from fighting on the frontlines. In Houthi-controlled areas, including Sanaa, Saudi airstrikes will constitute a significant threat due to frequent collateral damage. In territory under nominal government control, especially in the southern and western provinces of Aden, Taiz, Hodeidah, frequent terrorism and unrest incidents will drive incidental security threats to civilian operations. The provinces least affected by insecurity will remain Shabwa (except the province’s north-western districts), Hadhramaut, and Mahra provinces, as well as the Socotra islands.

The Yemen conflict will also continue to spill over in neighbouring states. Cross-border attacks against Saudi Arabia will persist owing to Riyadh’s enduring material and aerial support for pro-government forces over the coming months. Cross-border attacks against the UAE have grown comparatively less likely since the withdrawal of UAE-backed Giants Brigades from the frontlines. They nevertheless remain a credible threat, particularly in the unlikely but plausible scenario in which the Houthis rapidly lose significant swaths of territory to pro-government forces. In such a scenario, the rebels might conduct desperate cross-border attacks against the UAE to deter broader international support to pro-government forces.

Contract risk

Even where businesses and humanitarian entities are not impacted by security threats, operations are likely to become increasingly difficult in 2022 owing to further international restrictions on commercial interactions with the Houthis. With a military solution to the conflict out of sight and no peace talks underway, Western governments and multilateral bodies like the UN, have few diplomatic tools at their disposal to bring the Houthis to the negotiating table. Being unwilling to deploy military assets to incentivise cooperation, they will likely revert to implementing sanctions against the movement – despite their overall ineffectiveness. Notably, the US on 23 February introduced sanctions against a Houthi funding network, and the UN security council on 28 February voted a resolution calling the rebel movement a terrorist group (though this does not constitute a formal “designation”).

In imposing sanctions, foreign players will seek to prompt a change in Houthi behaviour by isolating the movement economically. And although future sanctions will likely be implemented with special provisions to ensure that basic goods and services still reach most Yemenis, the cost of compliance for operations in Yemen will increase significantly as the rebels effectively control much of the economic infrastructure in the north.