The COP28 climate summit will take place in Dubai (UAE) between 30 November and 12 December. The conference will gather government representatives of more than 200 countries, in addition to leaders of civil society and the private sector. In this note, we consider the prospects of the summit achieving its expected goals and its likely impact on climate agendas.

- Key agenda points will focus on negotiations over adaptation funding, a roadmap for the phasing out of so-called “unabated” fossil fuels and the fast-tracking of strategies for clean energy development.

- A lack of momentum in cooperation due to a persistently unfavourable global financial environment and growing geopolitical complexity will hinder the chances of reaching major agreements.

- However, the UAE’s close connection with the private sector means that measures positively impacting businesses are still likely to be announced, particularly around green finance and renewable energy.

- Although governments in most markets will continue to advance climate regulations, businesses will continue to receive limited direct government support to navigate net-zero-related challenges in the coming year.

Agenda

Given limited advances in international cooperation to tackle climate challenges over the past year, the COP28 agenda will be largely unchanged from COP27, with few exceptions including the addition of food and water systems and gender issues in the context of the energy transition. Key issues from COP27 – mainly around funding for adaptation, and the phasing out of fossil fuels – are still pending, and there is little evidence to suggest that they will be overcome at this year’s summit.

One example is controversy concerning the so-called “loss and damage” fund, whose creation was agreed at COP27, but its implementation remains contentious. This is mainly due to lack of clarity around its structure; while the US and other developed countries in the past few months have pushed for it to be hosted by the World Bank, emerging economies including China have advocated for the establishment of an independent structure. On 4 November, COP28’s Transitional Committee announced a draft agreement that stipulates that the World Bank will host the fund temporarily for an initial four-year period. The agreement’s presentation during the conference for further detailing and ratification will be a potential flashpoint.

Funding for mechanisms that have been agreed remains an issue. Developed economies continue to fall short on their 2009 promise to provide USD 100bn per year in climate finance to poorer nations. However, recent communications by the Transitional Committee have suggested that strong language setting clear and immediate commitments for richer countries on this regard is unlikely to be achieved during COP28, frustrating negotiators from developing countries and NGOs.

Another contentious topic that will be high on the agenda is negotiations around the phasing out of so-called “unabated” fossil fuels, referring to those that are used in power generation without carbon capture interventions to reduce their pollution intensity. While the EU and the US in the past few months have indicated their willingness to promote a more ambitious phase out, the proposal did not receive sufficient support during July’s G20 meeting in India, countries including China, Russia, South Africa and Saudi Arabia opposing it.

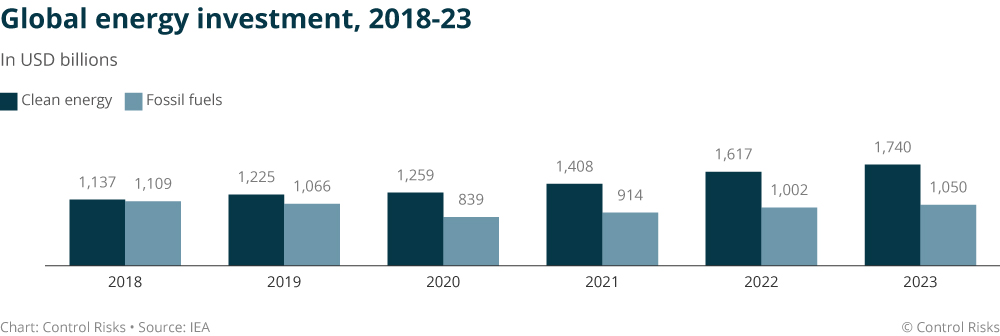

The controversial status of the concept of abating carbon emissions from fossil fuels among the scientific community has driven this contention. There is still limited evidence on the effectiveness of carbon capture systems, adding to concerns around the use of such mechanisms for greenwashing by highly-polluting companies and industries. Their implementation is also expensive and complex, requiring a combination of significant upfront infrastructure investments, policy incentives and supply-chain coordination. This controversy will likely flow through COP28 debates, reinforcing the historical and significant difficulties facing international cooperation with regard to fossil fuel-related reform. Although clean energy development is on the rise, investments in coal, oil and gas have remained largely steady across the past few years.

Geopolitics in the way

An increasing US-China rivalry and associated geopolitical fragmentation in the previous two years have undermined the momentum of international cooperation. Recent evidence suggests that competition has increased in the energy transition space. This has been illustrated by growing export controls introduced in the critical minerals sector, most recently China’s 20 October move to tightening export controls on graphite, a key material used in electrical vehicle batteries. Meanwhile, the EU on 13 September announced that it would launch an investigation into anti-competitive practices by Chinese automakers. US’s flagship climate effort, the Inflation Reduction Act, has also been a subject of criticism by other countries due to the considerable competitive impact of the programme’s subsidies package.

The ongoing Ukraine-Russia and Israel-Hamas conflicts add further complexity. Although their direct impacts on negotiations are limited, ahead of the conference major and middle powers have been focusing most of their foreign policy efforts on these conflicts rather than its initiatives, underlining the prioritisation challenges that consistently face climate agendas.

The persistence of high interest rates in many countries including the US for at least the coming year will sustain the challenge of financing climate agendas for governments and businesses. This is particularly true for adaptation projects – for which the economics tend to be more complex than mitigation projects – and for initiatives in higher-risk jurisdictions where political risk premiums will continue to represent an investment burden, such as many in Africa, Latin America and South Asia. According to data by Climate Policy Initiative, an NGO, global investments in adaptation between 2021-22 totalled USD 63bn, in contrast to USD 1.2 trillion for mitigation in the same period. Those with dual benefits totalled USD 51bn. Generally speaking, adaptation projects will continue to require a larger degree of government engagement than mitigation projects.

Business risk

While major government-led breakthroughs during COP28 are unlikely, this does not mean that there will not be meaningful announcements. The UAE’s close connection with the private sector means that measures further engaging businesses in the context of climate agendas are likely, particularly around green finance and renewable energy. Developments aimed at unlocking private capital through so-called blended finance instruments are likely, with a focus on finance innovation. In terms of emissions reductions, announcements might involve bolder methane targets and a new global pledge on cooling-related emissions.

Businesses will continue to face considerable operational, regulatory and reputational risks in 2024 related to the slow advancement of climate agendas. Any new agreements will take time to be translated into domestic-level regulation and implemented. Furthermore, the increasingly limited fiscal space for governments to support the private sector for either adaptation or mitigation projects will continue to force businesses to plan and implement their net-zero strategies without reliance on the public sector – a challenge that will ultimately become even more costly.

A lack of significant advances in international cooperation will also likely intensify a trend of growing social anxiety around climate issues around the world. This will drive increasing direct action threats related to environmental activism, with multinationals frequently being targeted if perceived, even if indirectly, as contributing to the climate crisis.