Hydrogen (H2) is the energy sector’s next big bet – and governments in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region are among those betting big on it displacing hydrocarbons as a major fuel for the world in the next two decades. This note examines how MENA has started investing in hydrogen to make sure it is not left behind in the energy transition to reduce the world’s reliance on oil and gas.

- MENA countries are embracing hydrogen to help bridge the gap for their own economies as the world transitions away from hydrocarbons.

- Hefty state support for the hydrogen pivot will continue to galvanise the development of blue and green hydrogen projects across the region.

- The sharp shock to the global energy system from the Ukraine-Russia crisis will continue to fuel a sharp increase in hydrogen interest from major economies.

- MENA’s decarbonising bet is likely to pay off with already guaranteed offtakers, but it needs to be quick to maintain its early-mover advantage.

The writing on the wall

As investment in a reduced hydrocarbon future gathers pace, hydrogen will play a key role as an alternative fuel to replace oil and gas. However, it poses a clear challenge to the hydrocarbon exporters from the MENA region who provide so much of the crude oil and petroleum products which currently power industries and road vehicles across the world.

Combined with the ever-growing renewable capacity in national power grids around the world, long-term decarbonisation over the next several decades is inevitable – even if it is a bumpy road ahead. Add in the short-term energy shock generated from the Ukraine-Russia crisis which has highlighted the benefits of diversified national energy systems which include oil, gas, and coal, and the long-term future of hydrocarbons is even more in doubt.

MENA countries have already started their pivot towards producing and selling more sources of energy – including hydrogen – to protect government revenue as the world slowly reduces its use of hydrocarbons.

“…Red and yellow and pink and green…”

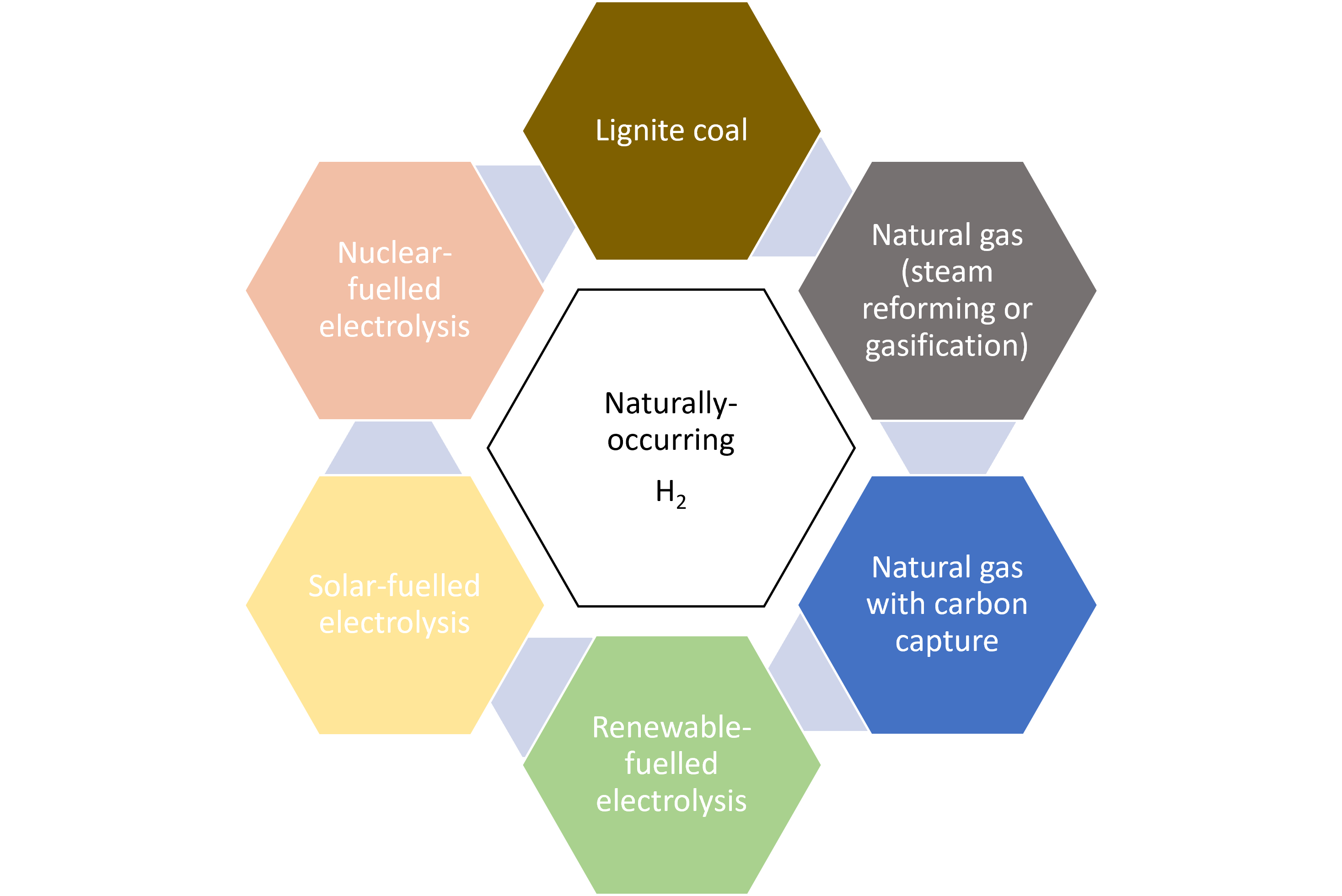

Hydrogen comes in a range of ‘colours’ with each one denoting the source of energy which fuels the process of its creation, and nods towards the process itself. ‘White’ hydrogen is the only naturally occurring type. Brown is created from lignite coal; pink from nuclear energy; yellow is created by electrolysis fuelled with solar power.

Blue hydrogen is more challenging to produce but holds more rewards – it is produced through gasification which separates the molecules in methane in natural gas, with excess carbon dioxide (CO2) being stored. Like yellow hydrogen, green hydrogen uses electrolysis but powered by all renewable energy sources (wind, solar, and wave) to create the fuel.

With some adjustments, hydrogen has the potential to replace diesel and other petroleum products as a key transport fuel. Its energy intensity means that beyond its role as a transport fuel, it is also a future replacement for diesel, natural gas, and coal in power generation for electricity, as well as for energy-intensive industries such as concrete, steel and petrochemicals production.

Finding this article useful?

Gas and renewables powering all

As it strives not to be left behind by the energy transition, blue and green, respectively, are where MENA countries hope to make their mark as low carbon or carbon neutral types of hydrogen. The region, and especially the Arab Gulf countries, has a clear advantage in the hydrogen game as a global supplier with widespread existing infrastructure of ports and pipelines.

Hydrogen as a fuel has been around MENA for a little while: Saudi Arabian national oil company (NOC) Saudi Aramco experimented with blue hydrogen technologies as early as 2019, when it installed a hydrogen fuelling station to power six hydrogen-fuelled vehicles in Dhahran. In September 2020, Aramco made its first ever shipment of 40 tonnes of ammonia to Japan as a test case for the hydrogen supply chain, including capturing 30 tonnes of CO2.

Green hydrogen is more expensive, requiring greater up-front investment for solar panels and wind turbines that are only now gathering pace as core energy infrastructure in MENA countries. But states across the MENA region are committed to expanding their renewables capacity in the coming decade which will allow them to follow through on green hydrogen – they have already taken big strides: by mid-2022 alone, the UAE has 5.8GW of operational capacity, followed by Egypt, Morocco, and Jordan with 4.8GW, 3.6GW, and 2GW respectively; Saudi Arabia has 7.1GW in various stages of development.

Across MENA, the development of green hydrogen plants will continue to gather pace over the next couple of years. Early-stage construction of the USD 5bn NEOM Green Hydrogen project in Saudi Arabia began in early 2022, which is due to produce 1.2m tonnes per year from 4GW of renewable energy from 2025 onwards. Egypt has begun development on a pilot 1 million metric tonne (mt) per year green ammonia plant in Ain Sokhna with French energy major TotalEnergies. Meanwhile, UAE state-owned energy companies ADNOC and Masdar have signed multiple deals in recent months to realise the ambition laid out in the country’s Hydrogen Leadership Roadmap to secure 25% global market share of low-carbon hydrogen by 2030.

North America and Western Europe are streaks ahead of MENA in terms of the total number of hydrogen projects in the pipeline: approximately 160 in total compared to MENA’s 47, according to industry publications. But MENA has an edge with its existing oil and gas infrastructure which can be retooled for hydrogen transport and export, as well as with the much more active role of government entities (and especially NOCs) in securing financing, supporting technological advancement, and ultimately managing these projects once operational.

The clear state backing for hydrogen and in making hydrogen the replacement for oil (or gas) in the future, tying hydrogen to state economic, trade, energy and foreign relations policies will create consistency in policymaking for the next two-to-three decades that the US and EU won’t be able to match because of the distance between the policymakers of the state and the private sector companies who are investing and building the infrastructure.

New challenges broaden hydrogen horizons

The fundamental shift in energy supply dynamics created since the Ukraine-Russia conflict broke out in late February have further fuelled a hydrogen-coloured future. With the European Union (EU)’s ban on Russian seaborne oil imports to be implemented from December this year, EU states are looking to fill that energy gap with natural gas and hydrogen and by extension diversify suppliers. The prospects of the EU as a major customer base further incentivises MENA’s development of H2 production and export facilities.

The future shines bright with hydrogen

With the price of natural gas remaining high due to the considerable demand caused by the EU moving away from Russia as a supplier, blue hydrogen production has become even more attractive: use gas but sequester the carbon to create an even better fuel to hit decarbonisation goals.

Continued state backing will create opportunities for foreign energy companies looking to make material investments and technological headway with hydrogen and hydrogen-adjacent systems. For large manufacturers who can benefit from hydrogen’s energy efficiency, there is likely to be state support to incentivise early adoption.

Growth in the sector will need to be consistent to maintain the region’s early-mover advantage against a growing array of rivals. In the short term, the hard work of building the plants in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and beyond – to produce, to export, even to use themselves – will continue to gather pace, putting it in a strong position to be a major supplier of hydrogen in the second half of the decade.