15 August marks one year after the Taliban took control of Kabul and effectively re-established its rule across Afghanistan. Since then, economic and governance challenges have only increased with little indication of respite for the group.

- Governance challenges for the Taliban will compound as the group continues to struggle to administer at the federal level and fails to deliver basic services, revealing limited governance prowess.

- Driven by growing security concerns, regional governments will engage with the Taliban but an imminent, formal recognition of the government remains elusive amid a worsening human rights record.

- Heightened capabilities of multiple militant groups, infighting within the Taliban and a growing Islamic State-Khorasan (IS-K) presence will lend to complex security threats and sustain a volatile operating environment.

- The economy will remain isolated due to frozen reserves, persisting sanctions and the suspension of foreign aid, while revenues that the Taliban accrues will remain insufficient sustaining the economic crisis.

Still searching for recognition

Executing a carefully planned out military strategy over the course of ten days in July 2021, the Taliban swiftly gained control of all border provinces and most provincial centres before seizing the capital, Kabul, on 15 August. As the last US troops withdrew at midnight on 30 August, the Taliban effectively established control across the country. However, one year later the insurgent group is yet to be recognised by the international community as a legitimate government.

In the year that has passed, Afghanistan’s troubles have exacerbated as the Taliban has struggled to govern and guarantee law and order. A growing humanitarian crisis has put 90% of Afghans under the poverty line and an economy near collapse has compounded governance challenges. A mass exodus of bureaucrats, technocrats, and skilled professionals following the Taliban takeover translated into an unprepared and under-equipped federal administration headed by militant leaders facing US and UN sanctions, and foot soldiers more privy with combat than with public service delivery.

A worsening human rights record and increasing numbers of arbitrary executions and detentions has further dashed the group’s desire to reinvent itself from an insurgent group into a legitimate political actor. Minority groups increasingly face attacks from the Taliban, as well as other militant groups, and extreme interpretations of Islamic Law have meant that the perceived “Taliban 2.0” is in fact no different from the Taliban of the 1990s, which for example restricted women from participating in the public sphere and barred girls from attending schools.

Humanitarian and security concerns will continue to drive international engagement with the Taliban as governments stop short of unilaterally and formally recognising the regime. While donor nations and multilateral agencies will continue to disburse aid directly to international agencies in Afghanistan, concerns about exposure to sanctioned militant leaders will limit engagements. Imminent recognition remains an elusive dream for the Taliban, made even more unlikely after the 31 July US drone strike that killed al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul’s affluent Sherpur area. The event – just days before the Taliban’s one year anniversary in power – will further undermine the Taliban’s appeals for international recognition, which partly rested on pledges detailed under the 2020 Doha agreement to deny al-Qaida and other militant groups safe haven. It will also reaffirm the concerns of Afghanistan’s neighbours and regional powers that terrorism may emanate from across the country’s borders.

Descent into chaos

Despite Taliban assurances to the international community, over the past year its affiliates including the Haqqani Network (HQN), al-Qaida, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and other militant groups with Central Asian links have increased operational capabilities and functioned with impunity, exploiting Afghanistan’s fragile security environment. Even anti-Taliban groups such as IS-K have burgeoned their file and ranks and improved intelligence-gathering and combat capabilities as the Taliban has struggled to retain control.

A deteriorating security environment and the plethora of active militant groups on Afghan soil has meant that the security threats to Afghanistan’s immediate neighbourhood will remain elevated. An uptick of violence in Pakistan’s tribal areas has prompted Islamabad to expedite efforts to fence the 990-mile (1,600 km) border with Afghanistan’s eastern provinces. Central Asian countries too have increased border patrolling and the presence of security forces along Afghanistan’s northern borders after noting increased skirmishes led by Afghanistan-based militant groups with Tajik and Uzbek links. China’s engagement with the Taliban has also been driven by heightened security concerns emanating from increased threats from the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM) – a Muslim separatist group that aims to establish an independent state replacing China’s Xinjiang province. Such groups are likely to further enhance operational capabilities and military strength as they operate with impunity in Afghanistan, thereby elevating regional and transnational terrorism threats.

Infighting within the Taliban will also heighten as social, ethnic and economic grievances come to the surface due to internal power struggles and growing disagreements between foot soldiers and the central leadership. Although the central leadership maintains sufficient control within the group to prevent an escalation, the presence of multiple militant patrons will continue to be a strong motivator for disgruntled Taliban fighters to break ranks and allegiances.

Economic crisis deepens

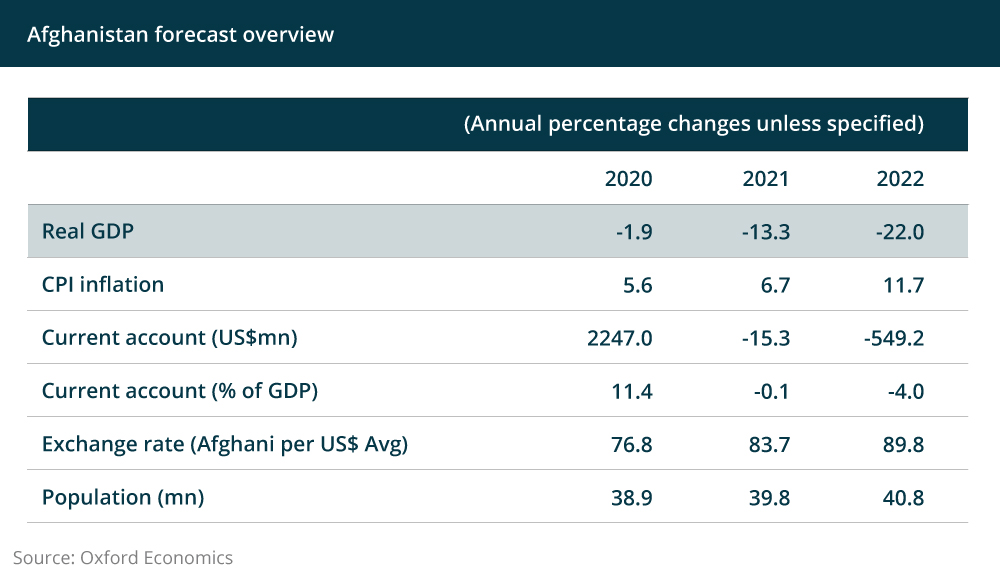

The abrupt cut-off of civilian and security aid, amounting to roughly 40% of Afghanistan GDP, immediately following the Taliban takeover dealt a severe blow to an already fragile economy grappling with severe drought, the COVID-19 pandemic and declining military spending in the wake of US troop withdrawal. The sudden halt in foreign aid has been further exacerbated by international sanctions, the freezing of Afghanistan’s foreign exchange reserves and foreign banks’ reluctance to do business with the country. The World Bank estimated in April that the Afghan economy has shrunk by approximately 30% since August 2021.

Since its takeover, the Taliban has derived its revenues and raised public finances from border taxes, customs duties, non-tax revenues and other alternate methods such as asset expropriation and narcotic cultivation and trade as seen during the insurgency and its previous rule (1996-2001). However, the group is unlikely to shore up enough revenue to account for a significant loss in international financial assistance. The World Bank estimates that the Taliban collected a total of AFN 75.6bn (USD 0.84bn) between December 2021 and June.

The Taliban has sought to tap into the country’s mineral and energy resources in order to increase its production and export. Afghanistan’s coal output and exports, mostly to Pakistan, are projected to double to four million tonnes this year since August 2021. However, the revenues are unlikely to contribute to public expenditure and will instead remain concentrated within Taliban ranks amid a lack of transparency and accountability of revenue collections and allocation.

In a bid to revive the economy, the Taliban has also been engaging with regional players such as China to attract investment in strategic sectors, such as mining. Nevertheless, exposure to international sanctions, a rapidly deteriorating security situation and the Taliban’s inability to facilitate business operations will continue to raise concerns about the risk, commercial viability and contractual challenges of investing in long-term projects.

The Taliban will also continue to demand and seek access to foreign reserves as it looks to revive a fragile economy that continues to be crippled by liquidity shortages. The Taliban has been engaging in talks with the US administration under President Joe Biden since June to discuss potential mechanisms that would allow the Afghan central bank to access USD 9.5bn worth of its reserves that are currently frozen in the US. However, particularly in the wake of Zawahiri’s death in Kabul, the US is highly unlikely to imminently lift financial restrictions.

Even as the Taliban continues to deny Zawahiri’s presence in the capital, its challenges are far from over. Since January, the economy has shown signs of stabilising but at a much lower equilibrium than prior to the Taliban takeover, leaving people poorer and more vulnerable to hunger and disease. As the Taliban focuses on retaining cohesion within its ranks and emboldened and equipped militant groups gain strength, Afghanistan’s security challenges will pose elevated threats to its neighbours and regional players. All of this continues to come against a backdrop of governance challenges that, even one year on, the Taliban is unable to solve.