Victor Tricaud, Analyst | Niamh McBurney, Senior Analyst

Just as regional governments had adapted to post-pandemic fiscal norms, the Ukraine crisis and fresh COVID-19 restrictions in China have driven a further reshaping of economic fortunes, with commodity producers cashing in while others struggle. We explore the regional impact of these dynamics.

In shock

As the scale of the shock to the global economy unfolded from early 2020 amid the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, even the region’s wealthiest economies were forced to seek external financing to extend social welfare support. This saw their debt-to-GDP percentages creep up. No sooner had governments adapted their budgets to post-pandemic norms, the Ukraine crisis and uncertain prospects for growth in China amid renewed COVID-19 lockdowns have driven new pressures.

Yet with these have come new opportunities. Revenue injections to commodity producers from unexpectedly high oil and gas prices have driven a sharp change in economic fortunes in just a few months.

In the money

Unsurprisingly, high oil and gas prices driven by uncertainty over Russian hydrocarbon supply and a recovery in the global economy as COVID-19 restrictions have eased have been a boon for the main Gulf Arab hydrocarbon exporters. Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Finance reported a 36% year-on-year increase in revenue over the first quarter of 2022. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), the region’s second-largest oil exporter, is benefiting from similarly positive revenue dynamics, while also capitalising on a post-pandemic increase in international travel and tourism. Meanwhile, Qatar, the world’s largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporter, has been courted globally for shipments as pressure on global gas supplies has risen amid the Russia-Ukraine crisis. The price of natural gas has increased by 127% since early January, significantly boosting Qatari government finances.

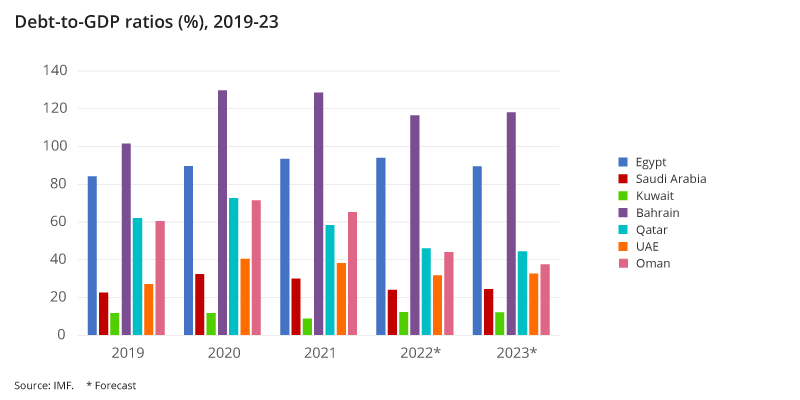

The governments of these three Gulf Arab states will use this extra cash to reduce their debt burdens and shore up foreign exchange reserves. All three are likely to see material reductions in government debt over the next two years. The IMF expects Saudi Arabia’s debt to drop to 24.5% of GDP in 2023 from 30% in 2021, Qatar’s to 45% from 58.4%, and the UAE’s to 32.7% from 38.3%.

A large amount will also be funnelled into sovereign wealth funds for both domestic and foreign investment. In all three states, these funds (or holding companies for state assets operating almost like a sovereign wealth fund) have become the preferred engines of growth.

Meanwhile, Oman – historically one of the most exposed of the Gulf oil producers to commodity price shocks – has also benefited from the recent oil price rises. The government has accumulated significant debt in recent years, with debt rising from 33.7% of GDP in 2016 to 71.4% in 2020 (with one IMF estimate as high as 81.2%). However, the introduction of the Medium Term Fiscal Plan in November 2020 established a clear path to reduce the annual fiscal deficit and slow debt accumulation. Combined with a 2022 budget that reduces operational spending, this has left ample room for the recent oil revenue windfall to contribute to debt reduction, enhanced by a primary budget surplus of OMR 357m (USD 927m) for the first quarter of 2022. The IMF now estimates Oman’s gross government debt burden to fall to 37.6% by the end of 2023 – dramatically reducing its risk exposure and allowing the government to move from a damage limitation policy to a true growth strategy.

Finding this article useful?

In the danger zone

Kuwait

From a sovereign debt perspective, Kuwait is in an even stronger position than its Gulf counterparts. Having similarly benefited from high oil prices during 2021 and early 2022, its nominal gross public debt is only expected to reach 13.2% by the end of 2022. However, the IMF forecasts gross public debt to climb to 42.2% by 2027, driven by the need to finance a growing primary deficit likely to be spent on the country’s social welfare system, the generosity of which is placing growing strain on government finances. With a gridlock between the executive and successive parliaments having so far endured for two years, and no clear end in sight, the prospect for fiscal reforms to manage the growing cost of welfare payments is poor. Although the current political deadlock means a required new law to issue new foreign-denominated debt is in limbo, a compromise will eventually be found to allow this legislation to pass. Once the government can return to international capital markets, political disputes on domestic economic issues are likely to deepen again as the debt burden rises.

Egypt

Egypt – one of the region’s largest economies – has for several years been in a cycle of borrowing to fund its economic ambitions. This saw total debt reach around USD 145bn at the start of 2022, equivalent to almost 95% of GDP. The IMF predicts that by the end of 2022 Egypt will have borrowed an amount equivalent to 7.1% of its GDP in 2022 alone, falling slightly to 6.5% of GDP in 2023.

The pandemic has not significantly affected Egypt’s economy. Although GDP growth reduced from 5.6% in 2019 to 3.6% and 3.3% in 2020 and 2021 respectively, the IMF forecasts growth of 5.9% in 2022 and 5% in 2023. With several loans maturing in the coming months, the Egyptian government is committed to repaying on time to assure international investors.

Nonetheless, with the government forced to dedicate one-third of the budget to debt servicing alone, this will reduce future funding for infrastructure and development projects. Combined with the rising pressures on government finances that will result from increasing commodity prices – to which Egypt is highly exposed given its historic reliance on wheat imports from Ukraine and Russia – high debt-servicing costs will undermine the long-term sustainability of economic growth.

Bahrain

Bahrain is the Arab Gulf state least well equipped to manage future fiscal and economic uncertainty. Although it has benefited from increased oil sector activity and higher prices, it has not experienced a similar fiscal windfall to Oman. Gross public debt reached 128.5% at the end of 2021, though is forecast to fall to 118.1% by the end of 2023, thanks to the Ministry of Finance’s Fiscal Balance Program. Nonetheless, even with this programme, Bahrain is likely to remain highly indebted and reliant on periodic fiscal support from the UAE and Saudi Arabia over the coming five years. Although this support will continue to prevent a sovereign default, austerity measures will remain a feature of Bahraini budgets for several years to come.

Preserving regional stability

Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE will likely use some of their oil and gas windfalls to support regional allies and broaden their foreign policy influence over the coming years. In some ways this will mark a continuation of the support that Arab Gulf states have provided across the region over the past decade to preserve political stability, in particular in Egypt, and thus the broader regional status quo. However, this time around the considerable size of cash windfalls and the maturing of Arab Gulf states’ own long-term development plans means they will be able to establish direct stakes in the success of the targeted economies.

This strategy will see them provide both direct assistance – via central bank deposits to support local currencies – and indirect support – through asset purchases of government-owned companies – to preserve political stability and foreign policy ties. Egypt and Bahrain are likely to be key targets of this support, with Egypt already receiving multiple investments from Saudi Arabia and the UAE. There will also be opportunities further afield for countries within the Arab Gulf sphere of influence. In the past month alone, Saudi Arabia has extended deposits it has made with the central banks of Pakistan and Yemen’s internationally recognised government.

The strategic sectors of logistics and transport, agri-food, hydrocarbons, renewables and telecommunications are all likely to be targets for investment. By buying these assets, Arab Gulf states will generate new income streams, reduce domestic vulnerabilities in the targeted countries – thereby boosting political stability prospects – and enhance their own long-term food and energy security.

When adding images copy the HTML this is in and alter the image. The image should always be 1000px wide.