We outline ten key issues to watch in Africa in the year ahead, including:

- The economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to be felt, with inflation and additional attempts at taxation likely to trigger cost of living protests.

- Tight elections will capture governments’ attention in three regional powerhouses, Nigeria, Kenya, and Angola. On the other hand, military leaders in four countries will seek to avoid elections to extend their transition regimes.

- Islamist militant groups across Sub-Saharan Africa are likely to further expand their reach in 2022, making new inroads towards the Gulf of Guinea and in East Africa.

- African countries will seek to push their climate change priorities when the continent hosts the COP27 summit in November. Decarbonisation will influence plans for energy generation, but also mining policy for strategic transition minerals.

1. Another year of pandemic...

The COVID-19 pandemic is certainly not the only health threat in the region, but it will be the one to continue to dominate headlines throughout 2022. It will also remain a burden on many governments’ constrained budgets, as it demands ongoing public spending on healthcare and social support – the latter as the pandemic has made people poorer – and continues to disrupt investment and development. This is either because companies and governments are cash-strapped as a result of the pandemic, or because trade and operations are frequently interrupted by travel bans as new variants continue to emerge. While most governments in the region have largely abandoned the restrictive approach from the early days of the pandemic – with some notable exceptions, like Angola, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe – their counterparts overseas are much more wary of ‘returning to normal’ amid higher caseloads and excess deaths. Meanwhile, the low vaccination rate is likely to remain an issue throughout 2022. Most countries reached less than 10% of their populations in 2021, and must now play catch up. However, the issues of yesteryear – including vaccine nationalism, affordability, and local distribution challenges – are still very much in play.

A healthcare worker prepares a dose of COVID-19 vaccine – Getty images

2. Rising costs of living

Inflation is on the rise around the world, and high prices will bring more turbulence in African countries. The World Bank projects annual inflation will exceed 10% in seven countries in 2022, including Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Angola, driven by rising oil prices, droughts and disrupted supply chains. Governments in Africa are less able than elsewhere to absorb the pain for citizens, and in some cases are even adding to the burden by levying taxes to plug shortfalls in government revenue. Protests against the cost of living and food insecurity, seen in countries such as Ghana or Malawi, will become more frequent in 2022. Unpopular policy reforms, such as the planned removal of fuel subsidies in Nigeria, will also face strong discontent and may ultimately be shelved. Governments will increasingly resort to price controls to avoid unrest.

3. Militaries try to settle in

Four countries – Chad, Guinea, Mali and Sudan – started the year with transitional administrations dominated by military officers, a record since the early 2000s. None are likely to hold elections in 2022. Despite newly imposed regional sanctions, Mali’s junta will further stall electoral preparations to gain at least another year in power. In Sudan, the military will rely on continued financial support from Middle Eastern backers to sideline civilians. We believe Guinea’s junta will seek a transition of at least three years, while Chad’s leaders will manoeuvre to extend their rule. Such transitions are inherently unstable, and at least one is likely to see another period of instability in 2022.

Even so, the warm popular reception to the coups in Mali and Guinea, and rising mistrust towards ageing political elites could embolden officers in other West African countries that present similar vulnerabilities. Burkina Faso looks set to join the same path after a coup on 24 January ousted President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré.

4. Kenya elections

The upcoming general elections scheduled for 9 August will be closely contested, as incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta is serving his second and constitutionally final term. A previous deal with Deputy President William Ruto under the ruling Jubilee Party of Kenya (JPK) was based on the understanding that each would mobilise their respective ethnic groups – Kalenjin and Kikuyu – to support the other’s presidential bid. However, Kenyatta has allied himself with veteran opposition leader Raila Odinga of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) at Ruto’s expense. Despite the powerful Odinga-Kenyatta alliance, Ruto’s populist campaign is gaining momentum among voters frustrated with the poor state of the economy. Political campaigning will intensify in the coming months and disputes between supporters of rival politicians will fuel security incidents. Nonetheless, the cross-ethnic nature of the emerging coalitions will likely mitigate the threat of widespread unrest, having to some extent defused traditional rivalries between various groups such as Kenyatta’s Kikuyu and Odinga’s Luo.

Finding this article useful?

5. Unprecedented times in Angola

Angola will also head to the polls in August or September in what is set to be the most tightly contested general elections in the country’s post-independence history. For the first time, the main opposition party, the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), has opened ranks to increase its chances of a wider victory. This marks a substantial shift in the country’s postcolonial political trajectory, where liberation movements-cum-political parties have typically tended to close ranks to protect their interests. The change comes as UNITA seeks to capitalise on heightened levels of popular discontent with the government led by the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), underpinned by six consecutive years of economic decline, high youth unemployment, and rising costs of goods and services.

We expect the MPLA and incumbent President João Lourenço to emerge victorious, enabled by the party’s vast organisational and financial capacity. For business, this is a plus, as it will entail broad policy continuity. However, civil unrest is likely to continue to rise in the run-up to the elections – and as the dust settles afterwards – resulting in higher-than-normal security risks across the country, particularly urban centres.

6. Nigeria gears up for elections

In Nigeria, politics will also take centre stage of national discourse as President Muhammadu Buhari enters his final year in office and the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) positions itself to retain political power after his handover on 29 May 2023. The APC national convention scheduled for February will kick-start an expectedly tumultuous electoral season – as political manoeuvrings commence within the APC and lead opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP). Early contenders such as APC party leader, Bola Tinubu, and former Senate (upper house) president Anyim Pius Anyim of the PDP will work to strengthen their respective political bases, secure support across various ethno-religious groups, mobilise mass voting blocs and build regional alliances ahead of the February 2023 presidential elections.

Buhari will make some last-ditch attempts to address economic and security challenges – including a 15.63% inflation rate, sustained threats across the country from Islamist and Niger Delta militants, banditry, separatist movements and urban crime. Government decision-making will however, slow down as the focus shifts towards elections, heightening non-payment risks and driving policy and regulatory uncertainty.

7. Spill over of militancy

Islamist militant groups across Sub-Saharan Africa are likely to further expand their territorial reach in 2022. In the Sahel, the al-Qaida affiliate Nusrat al-Islam (JNIM) will continue to make inroads into western Mali, northern Côte d’Ivoire and northern Benin, where it has already established networks. Attacks on security forces and local officials in rural areas of these countries will become more frequent. As militants establish themselves in northern Benin, the early emergence of a new front in the Benin-Niger-Nigeria borderlands is also likely in 2022. There have long been signs that groups with ties to militants in the Lake Chad region have been trying to establish themselves in northwestern Nigeria, capitalising on worsening insecurity. Meanwhile, Ansaru, an al-Qaida affiliate, appears to be re-emerging in Kaduna state.

Similar dynamics are also at play in Central and East Africa, as Islamic State (IS) affiliates in Congo (DRC) and Mozambique are deepening their reach. In 2022, militants in the DRC are likely to continue expanding their rural insurgency towards South Kivu and Ituri provinces. They are also likely to intensify their campaign of long-range attacks in eastern Congolese cities, and to a lesser extent in western Uganda and Kampala. In Mozambique, Islamist militants will continue to expand to new areas in the face of a regional military intervention. The conflict is likely to continue spilling over into the nearby province of Niassa and border areas of southern Tanzania.

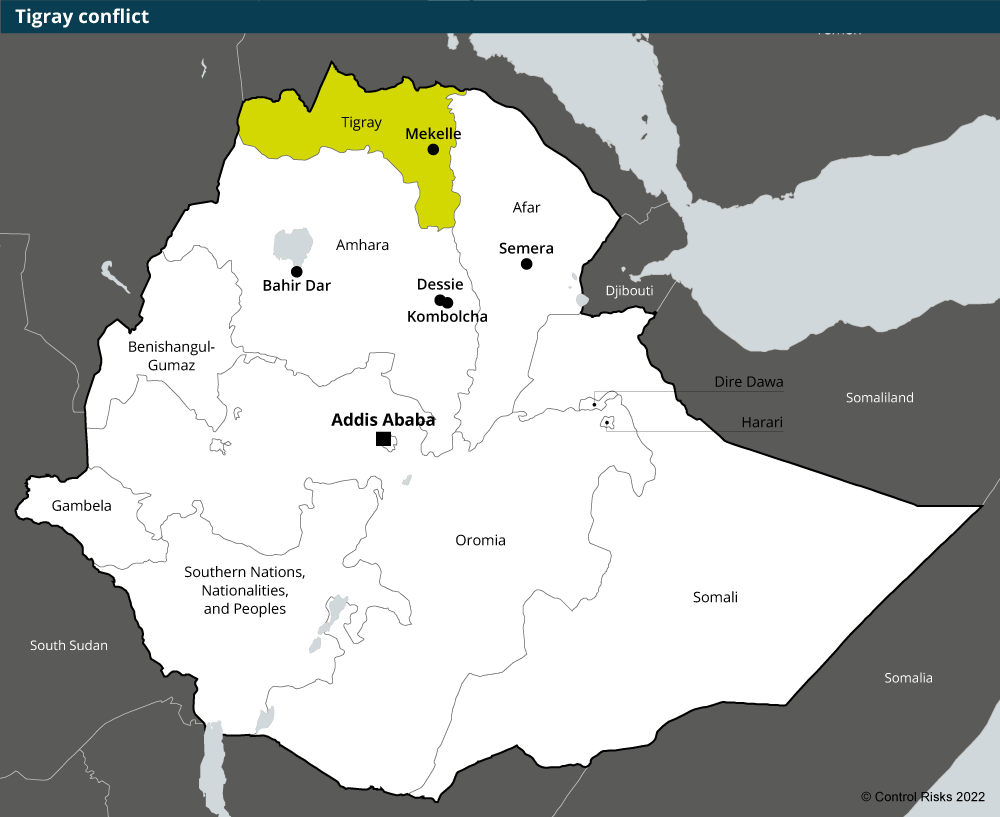

8. Ethiopia’s conflict

The conflict between federal armed forces and militias allied to the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) will likely persist in northern parts of the country in 2022. The conflict in August 2021 expanded into border regions of neighbouring Amhara and Afar regional states, though the federal government reclaimed territories across all three regional states in December 2021. Despite significant international pressure, prospects for a negotiated settlement remain unclear given the entrenched positions of both sides. Persistent reports of human rights abuses committed by both sides and the apparent reluctance of the federal government to address the dire humanitarian situation in Tigray will continue to attract international condemnation. Meanwhile, the conflict will also continue to strain government finances and undermine investor confidence.

9. The African COP?

The continent will host the next COP27 climate change summit in Egypt in November, giving African delegates an opportunity to shape climate discussions and push their priority areas, such as loss and damage, climate finance, adaptation or desertification. Having upped their net-zero commitments ahead of COP26, governments will continue to seek to diversify and decarbonise their energy sources, but transition plans will progress at different paces and towards different destinations. Small-scale renewable solutions such as mini-grids, C&I solar applications and energy storage systems are receiving growing attention from large donors. Some countries, such as Namibia and South Africa, have already obtained external support to explore their green hydrogen potential. But on a larger scale, gas will power on as the main transition fuel in 2022, with large projects coming closer to production or construction decisions in Senegal, Tanzania and Mozambique.

Following COP26’s pledge to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030, a surge in forest- and biodiversity-related climate finance is set to benefit African countries, especially in the Congo Basin rainforest.

Members of the Egypt delegation accept the next COP (Conference of the Parties) for COP27 which will be held at Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, during the COP26 Closing Plenary Part 1 on November 11, 2021 in Glasgow, Scotland. (Photo by Jeff J Mitchell via Getty images)

10. Decarbonisation feeds nationalism and geopolitical competition

Decarbonisation could also be a driver of resource nationalism and geopolitical competition in certain African mining markets, home to large deposits of critical “transition minerals”, such as copper, cobalt, lithium or nickel. These countries will be keen to leverage their strategic resources as a geopolitical asset: we expect bidding wars among Western and Chinese majors for stakes in promising deposits, and government decisions increasingly influenced by geopolitical considerations. The mining of these “future-facing” commodities will also serve countries’ recovery plans at a time of fiscal crunch. Not all countries will go for aggressive tax hikes: some, like Zambia under President Hakainde Hichilema or Tanzania under President Samia Suluhu, are keen to restore their country’s image with investors by improving dialogue with mining operators. But as African institutions nurture ambitions for an African battery value chain, mining jurisdictions will increasingly push operators to strengthen their commitments for local content and value-addition.