We assess the outlook for business amid rising geopolitical interest in sub-Saharan Africa, which has hosted several visits by senior international diplomats in recent months.

- Financial considerations will remain the primary driver of engagement by African leaders with international actors, with African countries choosing pragmatic non-alignment on global issues.

- Western and Gulf Arab countries will pursue increasingly transactional ties, especially as they seek to counter China’s position as a preferred infrastructure partner for many African countries.

- Meanwhile, Russia will push forward with its bid to replace France as the main security ally for countries in the Sahel, and seek to increase its influence elsewhere.

- Although African countries will likely benefit from increased investment in strategic sectors including infrastructure, energy and mining, geopolitical competition will precipitate new and aggravate existing regional tensions.

Flurry of activity

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa have played host to an increasing number of international actors since 2022. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz all toured sub-Saharan Africa in 2022, while US President Joe Biden held a US-Africa Summit in December 2022 and is planning his first Africa visit later in 2023.

The start of the year has brought further visits:

- China’s Foreign Minister Qin Gang visited Ethiopia, Gabon, Angola, Benin and Egypt from 9 January to 16 January.

- US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on 20-30 January visited Senegal, Zambia and South Africa. US First Lady Jill Biden also visited Namibia and Kenya from 22 January to 27 January.

- Russia's Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov visited Angola, Eritrea, eSwatini and South Africa from 23 to 27 January, and on 6 February visited Mali, Mauritania and Sudan.

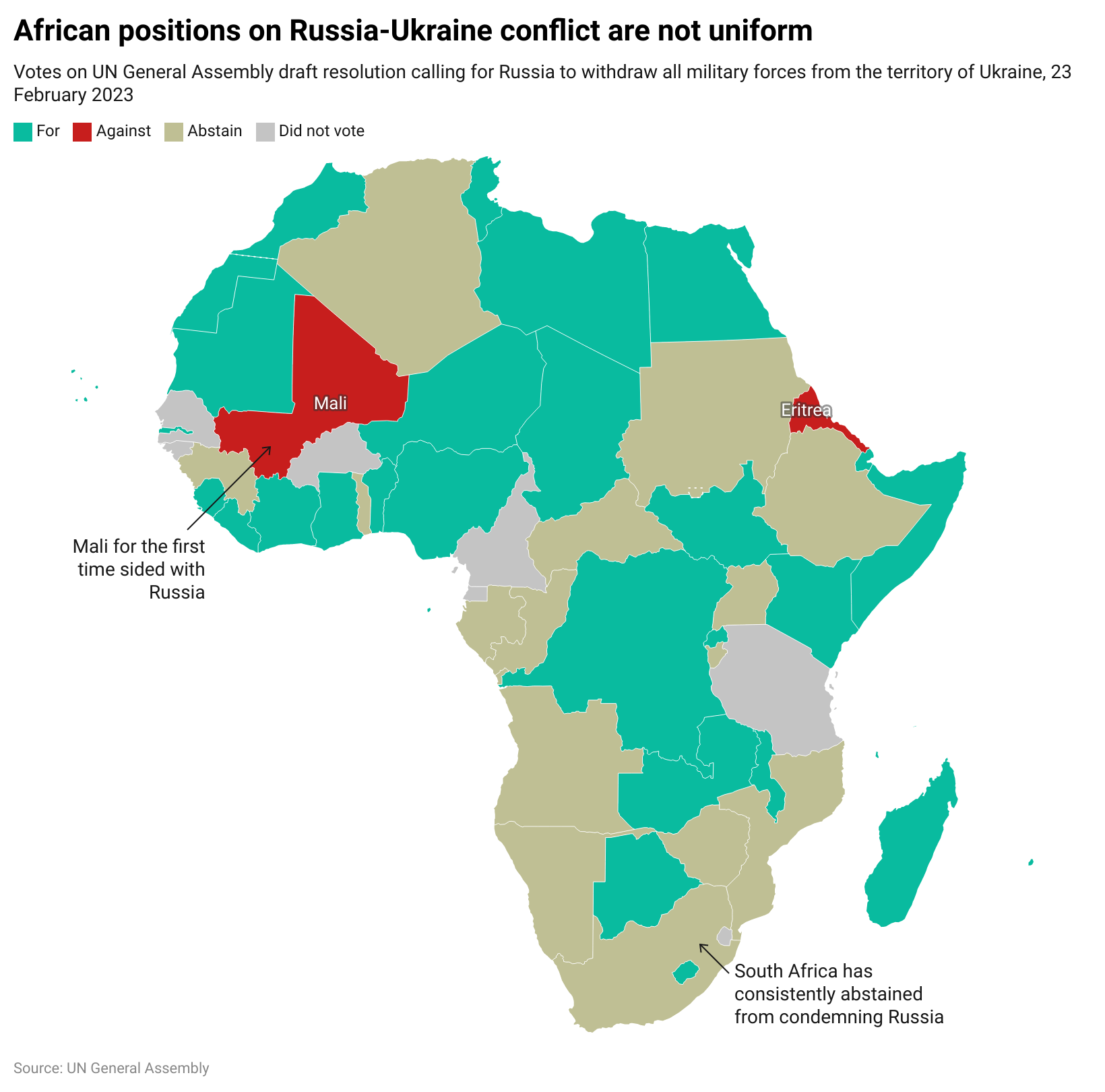

This increase in diplomatic activity has come at a time when geopolitical competition for influence has spiked, largely as a result of the conflict in Ukraine. Some Western governments were caught by surprise in March 2022 when 26 countries in Africa declined to vote for a UN resolution condemning Russia’s actions in Ukraine (one country, Eritrea, voted against the resolution). This number only fell slightly, to 24, when the UN General Assembly on 23 February voted on a similar resolution.

This non-alignment should perhaps not have come as a surprise. While many African governments formed close alliances with Western countries and multilateral institutions in the 1990s and 2000s, the rise in alternatives to Western financing has seen the influence of Western countries decline in the past decade.

Commercial considerations

China in particular has exercised its commercial clout and signed several agreements with African countries focused on developing large-scale infrastructure projects, including roads, railways and ports. The positive impact of Chinese-funded infrastructure improvements cannot be overstated, and has been one of several factors driving GDP growth in many countries, such as Ethiopia and Western governments, led by the US, have frequently criticised Chinese deals on the continent as “debt diplomacy”, given they involve governments taking on foreign-currency-denominated debt to finance at least part of the cost of construction. However, Western warnings have done little to curb African enthusiasm for strong relations with non-Western partners, especially China. Meanwhile, China has appeared to be an occasionally flexible lender, for example restructuring some of Ethiopia’s outstanding debt in 2018 and forgiving 23 loans to 17 African countries in August 2022. It is also engaging – albeit slowly – with Zambia on the latter’s efforts to restructure its debt.

African countries will continue to welcome their treatment by China as a more equal partner in their own economic development. Although we expect a slowdown in the pace and scale of Chinese-funded projects given domestic considerations on China’s part, African countries will likely seek to continue to build their relationships with China in the coming years.

In addition to China, Gulf countries – notably Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) –have become increasingly prominent on the continent. These countries have long had relations with majority-Muslim countries in North Africa. However, previous cooperation with countries in sub-Saharan Africa had focused on attempts to counter political Islam and the influence of rivals in the region, particularly following the diplomatic spat between Qatar and the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Egypt in 2017-21. African governments were keen not to take sides in that dispute, but instead benefited from pledges of investment from Qatar and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

As a result, the UAE has become another key infrastructure partner on the continent, developing a network of ports along the African coast. Qatar and Turkey have also funded several social infrastructure projects, becoming an important source of humanitarian and development financing in recent years.

Playing catch-up

In response, Western countries are following suit and will seek out more commercial relationships with African countries in the coming years. The US’s new Africa strategy, for instance, highlights the need to direct investment into Africa with a focus on healthcare, agriculture and energy, in tandem with its usual “soft power” efforts to improve democracy and government transparency.

Senior visits by US officials have also increasingly highlighted the US intent to secure access to critical minerals required to aid the energy transition away from fossil fuels. US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and Yellen in recent visits both emphasised the importance of collaboration on the development of electric vehicles, with the former visiting Congo (DRC) – the first visit by a senior US official to the country in more than a decade – and the latter Zambia, two major global producers of copper and cobalt.

These trips have yet to translate into investments of a size and scale to rival those of China, given other US domestic priorities. Nonetheless, we anticipate that the US will ramp up diplomatic and commercial engagement significantly in the year ahead. This is especially the case as the African Growth and Opportunities Act (AGOA), which gives African countries preferential access to US markets, is set to expire in 2025. Countries such as Kenya have sought to capitalise on this: on 13 February, Kenya and the US completed a first round of talks on a new Strategic Trade and Investment Partnership (STIP) to guide bilateral trade relations.

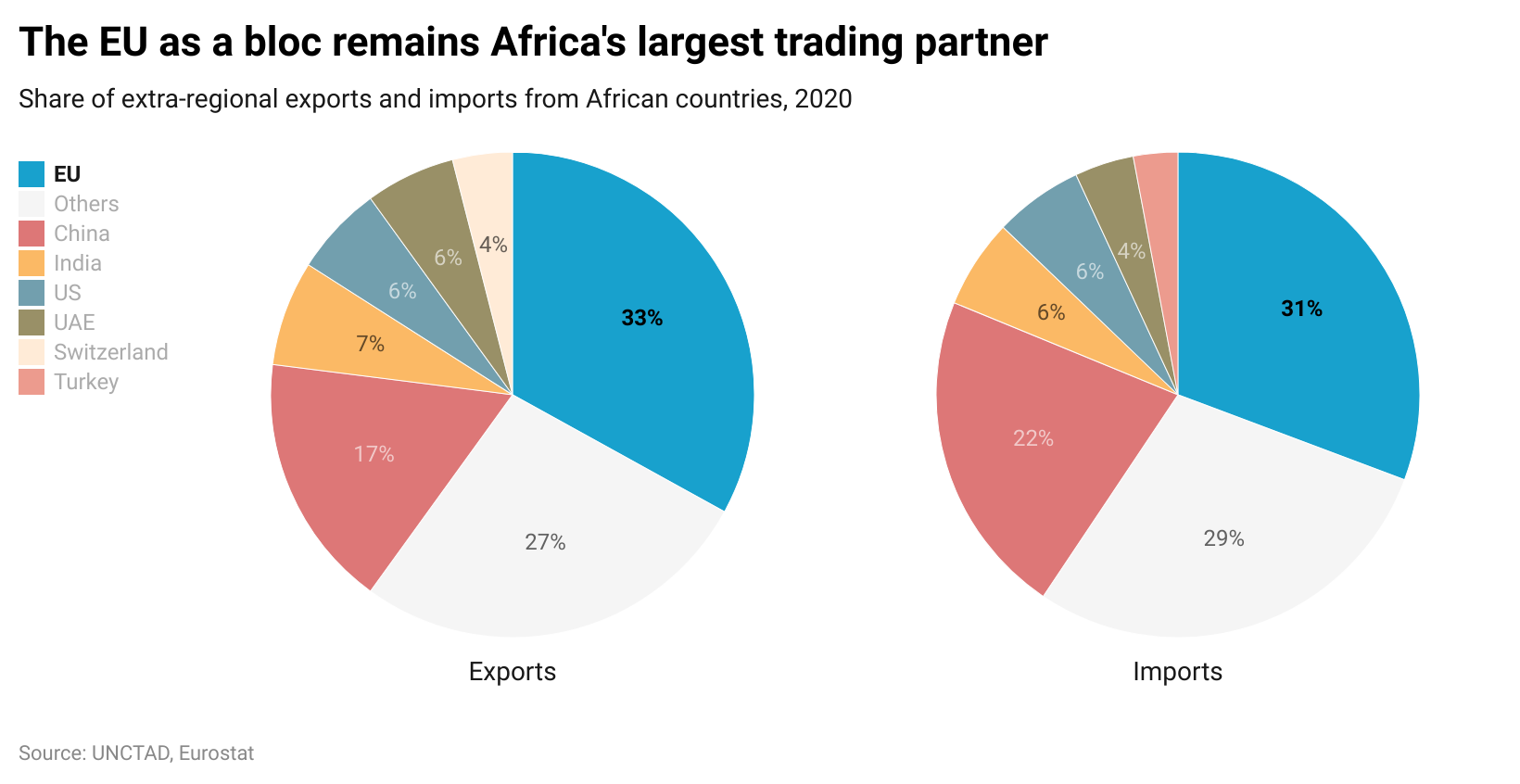

Meanwhile, European countries have also found themselves on the back foot in comparison with China. France, Portugal and the UK have witnessed a rapid decline in their political and commercial influence over the past decade. European countries are unlikely to recover the level of political sway they previously had amid the rise of other alternatives for African governments. Even so, the EU as a whole remains Africa’s biggest trade partner, accounting for 33% of extra-regional exports and 31% of imports in 2020.

Consequently, Europe will increasingly focus on strengthening commercial partnerships in the coming years, especially as the conflict in Ukraine has highlighted Western Europe’s dependence on Russian energy. In the coming years, European countries will increase exploration for both natural gas and newer energy sources such as hydrogen, demonstrated by German and EU interest in Namibia's green hydrogen sector.

In addition, the need to access critical minerals will increasingly shape European relations with African countries, with the EU keen to develop links with “reliable” countries and avoid dependency on a single country. Namibia in November 2022 became the first African country to establish a strategic partnership with the EU for the development of raw material value chains and renewable hydrogen.

Russia’s diplomatic test

Even as they up their commercial presence in Africa, Western countries will keep a close eye on the rising prominence of Russia. Russia in the past year has boosted its security cooperation with Mali and Burkina Faso, promising to aid governments struggling to contain spreading Islamist militancy. The military-led regimes in both countries have ended their longstanding security cooperation with France, precipitating the withdrawal of French troops.

There has been a notable rise in anti-French sentiment in the Sahel, with a commensurate increase in pro-Russia rhetoric among political leaders and on social media. In addition, media reports have implicated Russian private military contractor Wagner Group in human rights abuses and the alleged smuggling of gold from Sudan and countries in the Sahel.

Nonetheless, despite Western pressure, African governments are unlikely to shun Russian advances. A need to secure food, fertiliser and – for some – arms supplies will remain central to cooperation with Russia. However, a desire among many countries to avoid US and EU sanctions against Russia will also shape engagement, especially since cooperation with Russia does not typically result in financial or investment pledges for African countries.

As such, with a few notable exceptions such as South Africa, which has longstanding ties with Russia (showcased by joint naval exercises in February), Russian cooperation will likely be primarily focused on countries with military-led regimes or those facing severe security challenges, such as Central African Republic (CAR). The Russia-Africa summit due to take place in Saint Petersburg (Russia) in July, having been postponed from 2022, will be a key test of Russia’s appeal on the continent. African leaders will face strong pressure from Western governments to boycott the event.

Overall, we anticipate that African countries will benefit from this increase in geopolitical interest. Investments in infrastructure and energy, as well as partnerships to bolster food security will aid economies at a time when high global commodity prices are straining the finances of many African governments and populations.

However, the rise in geopolitical competition will also undermine some relationships. In the Sahel, the increased influence of Russia and divergent approaches by West African governments have become a major driver of friction within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Côte d’Ivoire and Niger in particular have remained committed to security cooperation with France and been vocal critics of Mali and Burkina Faso’s shift towards Moscow, as has Ghana. This divergence in choices of foreign partnerships has nurtured distrust among states in the region, which now prefer bilateral cooperation over regional frameworks to tackle growing Islamist militancy.

In addition, while this competition has subsided in recent years, Gulf Arab competition in Somalia has, for example, exacerbated tensions between the federal government in Mogadishu and regional government in Somaliland. Cooperation by Gulf Arab states with Sudan has also strengthened the position of military leaders there, while Western diplomats continue to urge a return to civilian rule. These dynamics will ultimately undermine political stability in these already fragile contexts.

Source: Control Risks