Russia will host its second Russia-Africa summit in St Petersburg on 27-28 July.

- The summit is mainly an opportunity for Russia to demonstrate its continued global influence and fight international isolation, despite Western sanctions.

- A secondary priority will be to grow alternative export markets for its products, mainly hydrocarbons and fertilisers.

- African countries have pragmatic reasons for maintaining dialogue with Russia, and some convergent interests in resisting alignment with Western countries.

- Investment and trade benefits will remain marginal, placing a limit on Russia’s co-operation with larger African economies. Russia will only gain a strategic commercial influence in a handful of small countries.

Hearts and minds

For African countries, St Petersburg is yet another stop on a busy circuit of “Africa +1” summits, with similar events held in the last year in Japan and the US. But the war in Ukraine gives this year’s event particular diplomatic significance.

For Russia, the summit is one of the most important diplomatic gatherings of the year: a chance for Moscow to show that despite Western sanctions, it is not isolated and it can maintain successful international co-operation with alternative partners. A top official in the Russian foreign ministry on 18 July said they were expecting representation from 49 out of 54 African countries, including “about half at the level of head of state”. The leaders of South Africa, Egypt and at least seven other countries have confirmed their attendance. 42 heads of state attended the first Russia-Africa summit in 2019, which marked the return to a more assertive Russian foreign policy towards the continent. Anywhere above 20-25 heads of state will likely be claimed by Russia as a diplomatic win, and a sign of its continued appeal as a partner.

Optics and politics

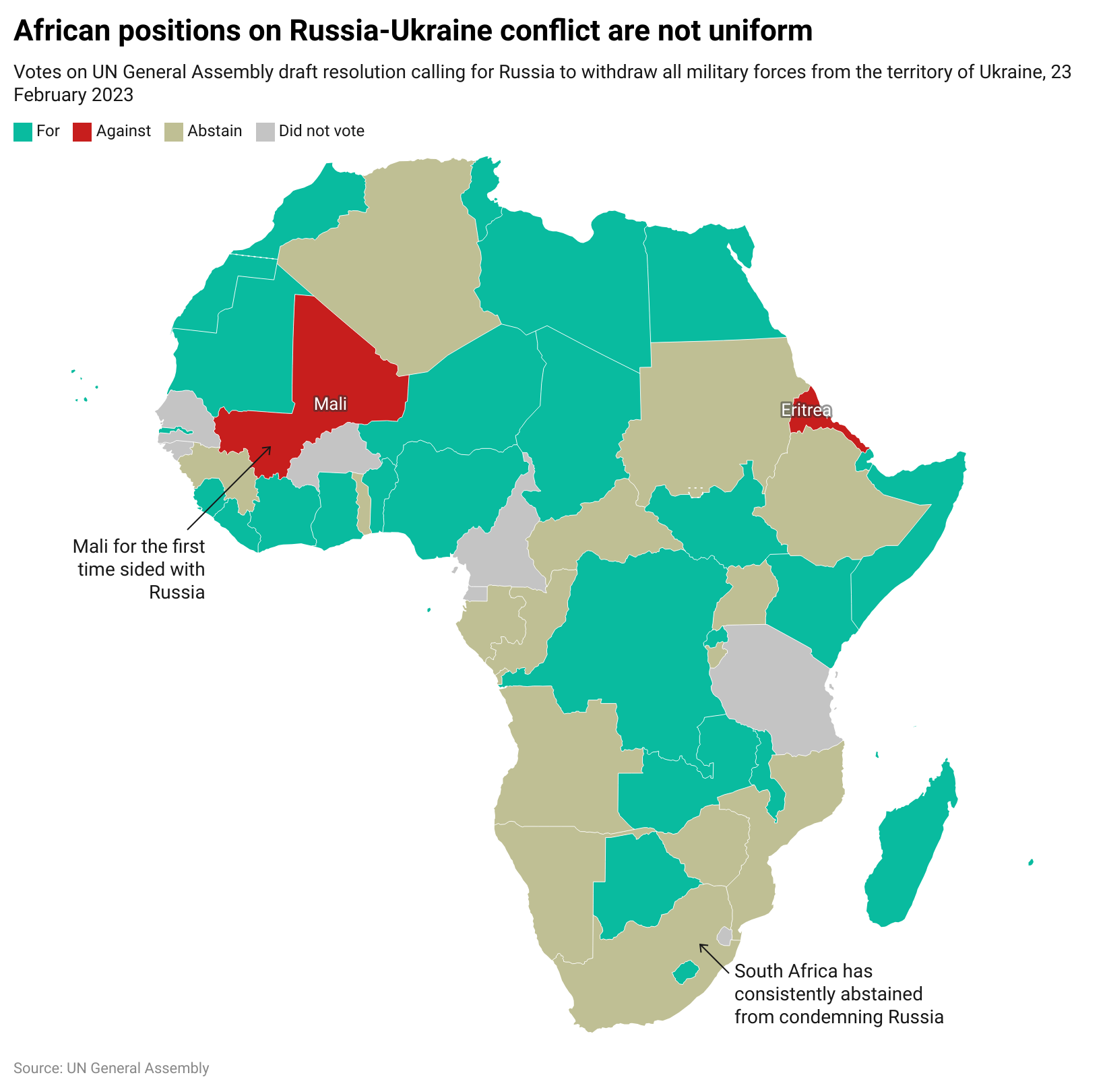

The summit will be far more about optics, and politics, than about trade and investment. Africa has gained an increased importance in Russia’s foreign policy in recent years, and even more since 2022. The 2023 update of Russia’s Foreign Policy Concept for the first time elevated Africa’s role as a “distinctive and influential centre of world development”. Russia views the continent, and its 54 votes in the UN General Assembly, as a key battleground for swaying the narrative against the West. Russia’s foreign minister Sergei Lavrov has been spreading Russia’s views far and wide, travelling to 15 African countries in the last year. Much of the summit agenda is articulated around the theme of sovereignty and resisting “new colonialism”.

Much to the frustration of Western diplomats, African countries also see a strategic interest in maintaining dialogue with Russia. This does not just rest on Soviet-Union-era sympathies or shadowy financial ties, as is sometimes assumed, but on plain pragmatic reasons. In hard economic times, many countries see it as financially sensible to maintain as many strategic options and sources of investment as possible. Beyond this, African countries also have some convergent interests with Russia in challenging the Western-led international order. They want to use ties with Russia as a launchpad for greater inclusion in the BRICS and in other international forums. Both sides are also keen on a level of de-dollarisation – Russia to diminish the impact of sanctions, Africa to reduce the costs of intra-regional trade. This does not amount to full ideological alignment, but creates enough of a case to maintain ties and resist alignment with the West.

What can Russia offer?

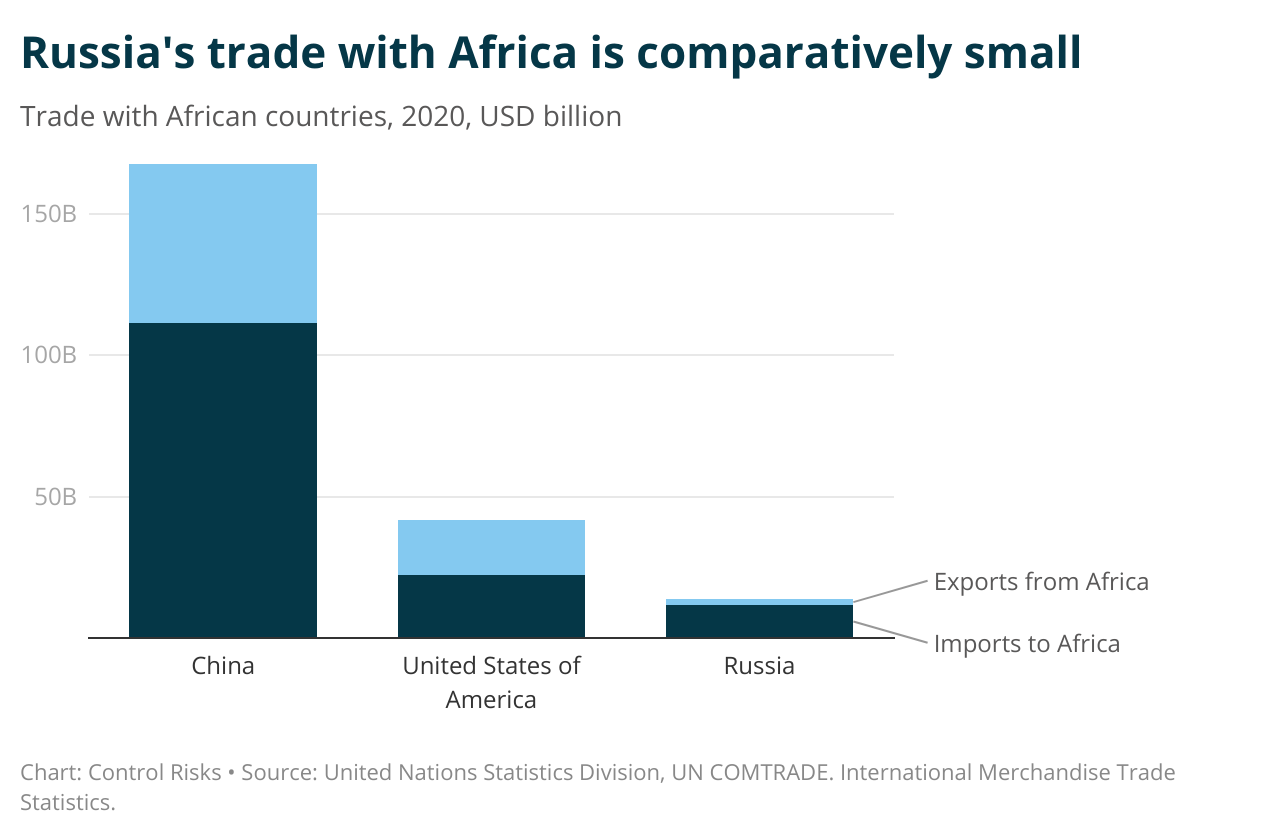

On the trade and investment side, Russia has much less to offer. It remains a minnow compared to other external players: it accounts for less than 1% of total foreign direct investment into Africa and in 2020 was Africa’s 17th-largest trading partner, trading a tenth of what Africa does with China.

Trade with Russia is also heavily imbalanced: African countries import five times more than they export to Russia. The 90+ trade agreements and USD 12bn of investment agreements signed at the Sochi summit in 2019 (according to the organisers) have not amounted to much, having been disrupted by the pandemic and Western sanctions. For most of the 2010s, the country was Africa’s prime source of weapons, well ahead of Chinese and European firms, but weapons inflows are likely to drop as Russia’s manufacturing capacity is absorbed by the war in Ukraine. On the other hand, Russia is increasingly keen to use African countries as new markets for some of its products or commodities that are barred from European markets, especially hydrocarbons. In the last year, Russian exports of refined petroleum products to African countries have increased nearly tenfold to reach a peak of 420,000 barrels per day in February-March, shortly after the EU imposed an embargo on Russian oil products. Africa also remains an important export market for Russian fertiliser producers. Russia has also resorted to fertiliser diplomacy to win favours on the continent, donating consignments of fertilisers to countries facing food insecurity, specifically Malawi, Mozambique and Kenya to date.

Russia will likely announce investment agreements and similar humanitarian donations as outcomes of a successful summit. For example, Gazprom is looking to support LNG or gas pipeline projects on the continent; Russia will also seek deals in nuclear co-operation, an emerging area of collaboration with African governments. However, such state-backed investments in energy infrastructure are also likely to be disrupted by sanctions and hostile lobbying from Western countries.

With-limits friendships

This lack of tangible economic benefits will put a ceiling on Africa’s engagement with Russia. The majority will maintain dialogue and trade ties with Russia, but this will mostly remain pragmatic and calibrated to raise their international profile without going as far as to antagonise Western partners. In the run-up to the St Petersburg summit, some African officials have expressed frustrations with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s lack of desire for peace. Russia’s recent decision to quit the Black Sea Grain Initiative, despite last-minute efforts by African leaders to salvage it, also casts a shadow over the summit: there will be talk of partnerships, but no unconditional love.

Among the continent’s largest economies, pro-Russian views run deepest in South Africa, which has found itself in hot water with the US, especially after the US ambassador in May accused the country of covertly supplying weapons to Russia. The revelations have damaged to the US-South Africa relationship, and exposed the country to a possible exclusion from US trade privileges (AGOA). After the St Petersburg and BRICS summits are over, the country will likely focus on repairing the damage by limiting further US scrutiny into its Russia ties. Just a few days ago, on 19 July, it resolved a diplomatic headache when it confirmed Putin would attend the BRICS summit virtually rather than in-person in Johannesburg; as a party to the International Criminal Court, South African authorities would have been legally required to arrest him on arrival.

Egypt is a strong runner-up when it comes to pro-Russian interests. The north African country has been a large importer of Russian grain, on which it depends to ensure adequate supply of bread – a key food staple in Egyptian culture. Underscoring deepening bilateral co-operation, a US intelligence document leaked in April purported to show that Cairo was intending to supply ammunition to Russia to support its war in Ukraine, possibly in exchange for grain supplies. Notwithstanding ongoing strategic ties, the US remains a vital partner for Egypt, so Cairo has remained careful to maintain a delicate balance. Notably, mere days after accusations of having intended to discreetly supply weapons to the Kremlin emerged, Egypt publicly agreed to manufacture weapons for Ukraine.

Kenya also illustrates this balancing act: having initially lambasted Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the UN Security Council, it hosted Sergei Lavrov in May to discuss a bilateral trade deal. Engagement will be most limited with Nigeria, which has had comparatively less dealings with Russia. New president Bola Tinubu does not appear to have an affinity for Russia affinity and is instead more likely to focus on ties with the US.

In most countries, Russia’s influence over the business environment will remain limited to trade in certain commodities. Though the St Petersburg summit will likely result in investment MoUs, Russian firms are unlikely to have the diplomatic backing and resources to turn these into competitive investment bids in strategic sectors. These countries are also likely to be wary of US enforcement of secondary Russia sanctions, and to refrain from offering a haven to Russian sanctioned entities in a systematic manner.

Tier one friends

Only a handful of smaller countries, for opportunistic reasons, have embraced a more strategic partnership with Russia, making it their primary security partner. Eritrea and Sudan have also been traditional Russian allies, though engagement with the latter is complicated by the ongoing conflict. It has also forged alliances with Central African Republic, in Mali and eastern Libya’s strongman General Khalifa Haftar, propping up fragile regimes and domestic allies through private military deployments, which are likely to continue despite the recent Wagner mutiny. In these countries, Russia also acts as a disrupter, with more substantial impacts on the business sphere: we have seen consistent efforts to stoke anti-Western sentiment, and aggressive efforts by Wagner-linked companies to take local market share away from Western (mainly French) competitors. In exchange for political support, these regimes are also more likely to act as conduit for financial transactions with Russia, increasing their exposure to sanctions violations. This was illustrated in May when the US warned of Mali being used as a conduit for Russian arms purchases intended for the war in Ukraine.

However, Mali and CAR Wagner’s mutiny has weakened Russia’s brand as a reliable security partner, limiting its appeal and ability to expand to larger countries in the region.

What to watch in St Petersburg

- The seniority of African delegations in St Petersburg, and Putin’s choice of bilateral meetings, will give an indication of Russia’s closest partners and “targets” on the continent.

- Russia will seek to announce a flurry of trade deals and investment MoUs to project business as usual. Defence co-operation or military assistance agreements would be more impactful.

- African leaders will plead with Putin to reconsider Russia’s exit from the Black Sea Grain Initiative. A firm refusal to make any concessions could sour the mood and tarnish other outcomes. On the other hand, Russia would score a diplomatic win if African countries endorsed its call for Western sanctions on the Russian Agricultural Bank to be lifted. In a letter to African leaders on 24 July, Putin assured that Russia would be capable of “replacing the Ukrainian grain both on a commercial and free-of-charge basis”. Bilateral grain deals are likely to be agreed with “friendly” countries.