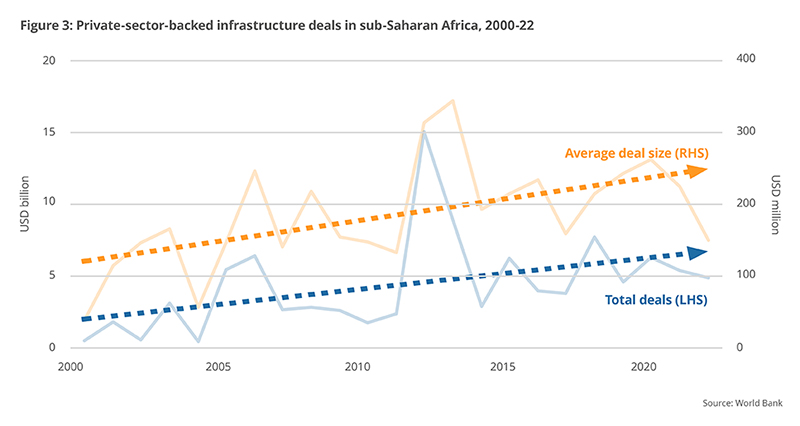

Africa is facing a dire infrastructure funding gap, one that traditional partners are unable to fill. The region requires an additional USD 100bn annually to meet its infrastructure needs, according to the African Development Bank (AfDB). This picture looks increasingly dire when we consider that Africa saw the largest decrease in FDI between 2021 and 2022 of any region globally, declining 44% over this period, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

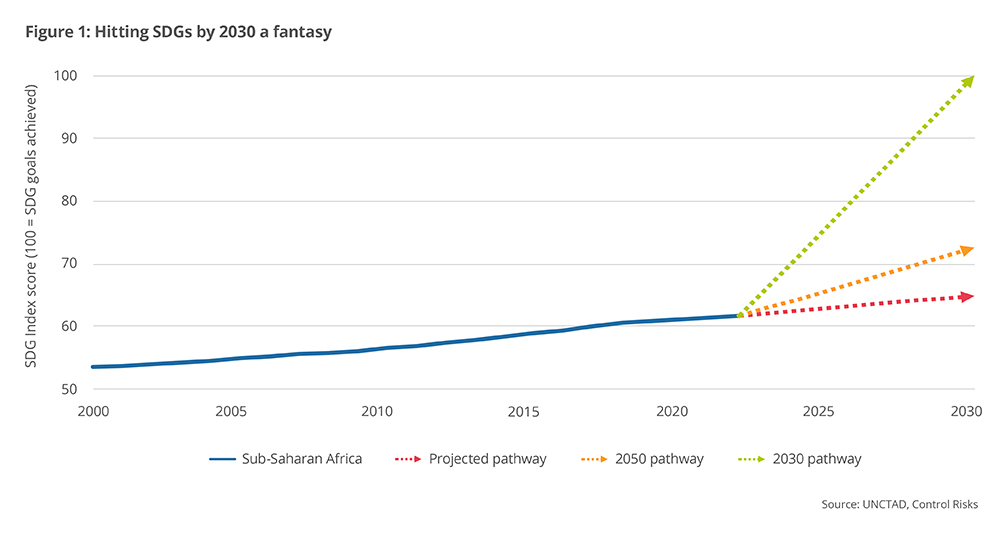

According to UNCTAD estimates, the largest funding gaps to reaching sustainable development goal (SDG) targets are in hard infrastructure – energy, water and sanitation, transportation, and telecommunications – which account for roughly 57% of the total investment required. Based on Control Risks’ analysis of UNCTAD data, sub-Saharan Africa would only meet its SDGs in 2117 at the current pace of investment.

Sovereign debt issuances are drying up across Africa due to high global inflationary pressures and punchy interest rate responses by central banks. Heightened debt service obligations for governments and limited bilateral support have meant that attention is turning to private market investors and project finance teams to help fill the infrastructure gap.

Infrastructure still secondary for development partners

China’s infrastructure investment under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is seeing a major downturn, following reports of a 55% drop in Chinese investment inflows in Africa in 2022. Meanwhile, the commitment of Western governments to fill this funding gap and counter Chinese influence in Africa remains unclear. Infrastructure is but a marginal piece of US President Joe Biden’s USD 55bn commitment to the continent over the next three years.

Hard infrastructure is also the main hurdle to implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and climate change adaptation targets. For example, the AfCFTA hinges on competitive trade costs between countries, but this continues to be prohibitive due to infrastructure that is not fit for purpose. Even some flagship infrastructure projects completed in recent years are not designed to withstand higher projected temperatures and rainfall anticipated over the coming decades, thereby reducing economic resilience and potentially harming productivity, livelihoods and food security over the long term.

Private-sector financing can help fill the gap

The lion’s share of infrastructure projects remains stuck at the scoping and pre-feasibility stages due to a lack of funding commitments, reflective of the poor visibility and bankability of proposed projects. A country’s regulatory framework and governance are also strong predictors of whether a project will obtain financing, showing that government reform is often a prerequisite for private debt and equity financing.

Although it is true that the internal rate of return (IRR) is lower for infrastructure than other asset classes, private markets investors often cite infrastructure’s provision of a steady and predictable income stream and an inflation hedge as a key advantage. This regular return is especially compelling for investors amid the current global economic environment, not to mention for the positive social impact and progress towards SDGs associated with infrastructure investment.

Based on our recent experience supporting infrastructure investment for private investors, we have identified a number of sub-sectors that could provide both meaningful returns and impact in the region:

Renewables

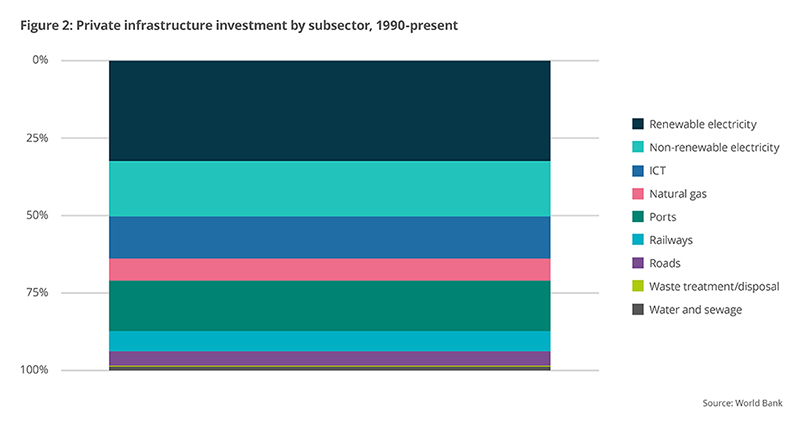

This is by far the largest infrastructure segment for private-sector investors, as shown by historical investment flows (see Figure 2). The focus from the private sector on energy is proportionate to the needs identified by UNCTAD, but it is still far below what is required to meet the SDGs. We are seeing some gains in recent Renewable Independent Power Producer Programme (REIPPP) rounds in South Africa supporting new private-led generation capacity, but despite some government subsidies and other incentives, the government continues to face challenges in attracting investors. Heading further north, the rekindling of the Grand Inga dam project in Congo (DRC) could alleviate loadshedding and reduce dependence on non-dispatchable renewable energy sources over the long term in southern Africa. However, substantial technical, financial and environmental challenges will need to be overcome. And it does not resolve long-standing deficits in transmission network investment, nor the pervasive issues of electricity theft and fraud that continue unabated, exacerbating grid inefficiencies.

Power-to-X

Power-to-X projects, and green hydrogen projects in particular, offer the possibility to tackle both energy generation deficiencies and industrialisation, as sub-Saharan Africa gets closer to becoming a vector in global hydrogen supply and large-scale energy storage. Projects are increasingly moving from hypothetical MoU stages to detailed feasibility studies, for example with the Hyphen project signing feasibility and implementation agreements in May 2023. Such developments are accelerating fundraising efforts and will provide more tangible opportunities for investors to back.

Critical minerals export and value-added processing

As the geopolitical battle between world powers intensifies for the control of critical mineral supply in Africa, there will be an increasing need to finance export corridors and related infrastructure to support domestic mineral processing. We note that the US Development Finance Corporation is considering a USD 250m investment in the Lobito railway corridor from DRC to Angola for copper-cobalt exports. This supports economic diversification ambitions in Angola, but also increases export options in the copper-cobalt supply chain. We expect an increasing number of conditions to be attached to such investments as several countries in the region ramp up their indigenisation and beneficiation push in energy supply chains. For example, Zambia and DRC signed an EV battery co-operation agreement in December 2022 to support development of the value chain domestically. The authorities in Guinea-Conakry have since late 2021 turned the dial on bauxite miners to work towards domestic processing into alumina, while Ghana recently announced a green minerals policy to support the development of its lithium industry that would explicitly prohibit raw lithium exports. There are notable impact opportunities because of this trend, as nearshoring has social benefits because of increases in domestic know-how and revenues, and it also reduces Scope 3 emissions – indirect emissions that occur upstream and downstream from an organisation – across supply chains.

Global and intra-regional connectivity

Transport and telecommunications infrastructure will be the cornerstones of AfCFTA convergence – the minimum architecture for the regional free trade area to work. Indeed, an oft-cited fact is that it is cheaper to export a container from Europe to many countries in Africa than it is to move it between African countries or even within a single African country. Vital to reducing these costs and enabling intra-regional trade will be investment in natural resource pipelines, increasing port throughput capacity, developing major road and rail arteries, and expanding fibre-optic cable networks and mobile network coverage. Progress in these areas will support long-term economic, political and digital inclusion, especially where infrastructure is designed to withstand future climate scenarios. Even though there will continue to be heated debates around the merits of building new natural resource pipelines in the region as climate change increases the urgency for an energy transition, there is no question that such infrastructure would have developmental benefits for Africans as a result of increased government revenues, job creation and African economies’ access to global energy markets.

Urban water supply, waste management and treatment

Even a fleeting visit to major African metropoles shows that the urbanisation challenge risks overwhelming local governments, as investment in public services fails to keep pace with urban population growth. Water supply, waste management and treatment are underinvested in by the private sector, in part because these are onerous and lower-return asset sub-classes. However, as many countries in the region face severe water stress and a higher frequency of extreme weather events, resilient water and waste treatment infrastructure will be vital to mitigating flood risks and waterborne disease transmission, while boosting public health. Governments across the region can thus consider loosening state control over water infrastructure and allowing more opportunities for private investors.

Risks can be mitigated, but African governments can do more

The risks associated with infrastructure pose a major obstacle to a moving away from higher-return asset classes such as technology and health. Such risks can manifest in situations such as sudden changes in government, where infrastructure projects are large, visible targets that can be subject to politically charged contract review processes with unpredictable outcomes. Navigating these complexities requires a comprehensive approach to risk management and due diligence, which is why quality and actionable intelligence is vital. This includes having a nuanced understanding of government procurement processes, the sometimes-undue influence of stakeholders, and evaluating ESG impacts on local communities.

Nevertheless, African governments can improve their messaging and pitch:

They can make the case more persuasively that infrastructure investment can improve IRR on adjoining projects, and so have a compounding effect on development and investment returns in the region. National and cross-regional development plans are showing signs of progress, with examples such as the Emerging Gabon Strategic Plan (PGSE), the Trans–West African Coastal Highway from Lagos to Dakar, or the Kenyan government’s revival of LAPSSET often cited as success stories. But many proposals still struggle to get off the ground because of poor economic viability, and even relatively successful initiatives are still lacklustre when it comes to meeting industrialisation promises.

Governments can better articulate their infrastructure needs and target relevant investors. Bespoke investor roadshows offer a means to illustrate where funding gaps need to be met and what positive impact (in SDG terms) the infrastructure will bring about.

It is not only about greenfield or PPP projects. The maintenance and rehabilitation of existing infrastructure will be just as important as shiny new projects, and governments should encourage private-led initiatives to support this. Private developers have on a number of occasions proposed rehabilitation of dilapidated railways and roads, but many proposals fail due to onerous government demands that reflect a desire not to have the private sector take over service provision.

Conclusion

SDG targets will not materialise this decade without a paradigm shift in how governments create incentives for private investors. Although infrastructure’s steady and predictable IRR is attractive during economic crises, this investment cannot be forgotten in times of plenty. The solution to this is likely to be found through a mix of government incentives and well-formulated infrastructure strategies, in addition to a renewed push from multilaterals and development finance institutions to support leading initiatives such as the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG) and Africa50.

Although it is true that infrastructure can create an enabling environment, it needs to be supplemented by productivity gains in industry, manufacturing, or agriculture. Investment flows in Africa have often been reflective of a chicken and egg situation, where local demand conditions are deemed not to meet minimum thresholds to justify the infrastructure. This arithmetic can be improved by addressing the local conditions side of the equation, cutting red tape for investment in industrial sectors that stand to benefit from planned infrastructure corridors.

Investors can also position themselves by engaging more with local governments and targeted infrastructure funds, and by bringing them together with project developers that are at the scoping and pre-feasibility stages. Although the commercial and financial viability of a given project will ultimately determine capital allocation, governments have an incentive to support progress towards the 2030 SDG agenda and may thus consider fiscal exemptions and other forms of incitement. Such mitigating factors can reduce financial risks and should be considered when making IRR estimates and valuations. When added to quality intelligence around impact and operational risks, such as a project’s ESG credentials, integrity and regulatory issues, investors can increasingly view infrastructure as a stable and viable asset class rather than a poor performer.