Increasingly, the Kenyan government is trying to leverage local institutional capital to fund infrastructure projects. These efforts are driven by dwindling external funding due to shifting geopolitics, as well as sustained challenges to the country’s sovereign debt against the backdrop of its infrastructure deficit.

Shifting foreign investor priorities stifling FDI inflows

Although World Bank estimates have placed Kenya’s yearly infrastructure financing gap at around USD 2.1bn for more than ten years, the value of private investments into public-private partnership (PPP) infrastructure projects in Kenya has recently been on a downward trend. PPP financing has declined 91% from 2023, going from USD 353m to USD 33m in 2024, having been even higher in 2022, at USD 624m. The sharp decline since 2023 can largely be attributed to the cancellation in November 2024 of airport and energy transmission PPP contracts with the Indian Adani Group, which were valued at around USD 2.5bn, due to widespread integrity concerns.

More broadly, shifting investment priorities in the Global North – such as the US’s “America First” approach – will likely sustain cuts to infrastructure project funding, especially for social infrastructure. This has already been demonstrated by the US government’s discontinuation of Millenium Change Corporation project funding. This is exacerbated by Kenya’s debt-to-GDP ratio, which has risen from 39% of GDP in 2010 to 72% in 2025, underscoring an increasingly constrained fiscal capacity for the government to finance infrastructure projects.

High infrastructure demand drives domestic capital ambition

Against this backdrop, the Kenyan government is increasing its efforts to expand the role of local institutional capital in infrastructure financing. This culminated in January in National Treasury Permanent Secretary Chris Kiptoo forming a committee of experts from the private sector to explore and recommend policies for mobilising long-term capital from local financial markets for infrastructure projects.

A couple of weeks later, the promoters of a USD 3.5bn 440-km expressway project between Nairobi and Mombasa in Kenya, dubbed the USAHIHI project, announced they would raise an unprecedented USD 1bn bond through local pension funds, investment banks, and insurance companies. These developments underline the local currency impetus of both the public and private sector.

In particular, both the government and private sector have identified pension funds, which hold assets totalling approximately USD 15.5bn, to meet part of the capital demands for infrastructure projects. The pension industry has acknowledged the role that the private sector should play in advancing Kenya’s infrastructure agenda, and it has mounted calls for suitable financial instruments to increase its ability to participate in infrastructure financing. However, Kenyan regulatory restrictions, institutional misalignments, undeveloped financial markets, and transparency concerns will likely impede efforts to sufficiently mobilise capital if not addressed.

Kenya’s infrastructure gaps are critical to growth

Kenya’s need for investment into strategic infrastructure such as roads, energy, and airport infrastructure remains critical to sustain and develop economic activities. For instance, in the energy sector, Kenya is facing the dual challenge of aging transmission infrastructure and increasing pressure on power generation capacity.

Energy transmission’s USD 3.8bn financing gap

Inadequate and aging transmission infrastructure contributes to approximately 23.65% in energy system losses, which are then borne by the consumer through increased energy costs, electricity supply inconsistency, and elevated operational challenges for industrial operators. To remedy transmission issues, the Kenya Transmission Company (KETRACO) has outlined the need to expand the transmission network and estimates that it would require an estimated USD 4.8bn, with a funding gap of USD 3.8bn, highlighting the scale of outstanding capital requirements.

Increased load-shedding risks due to energy generation shortfalls

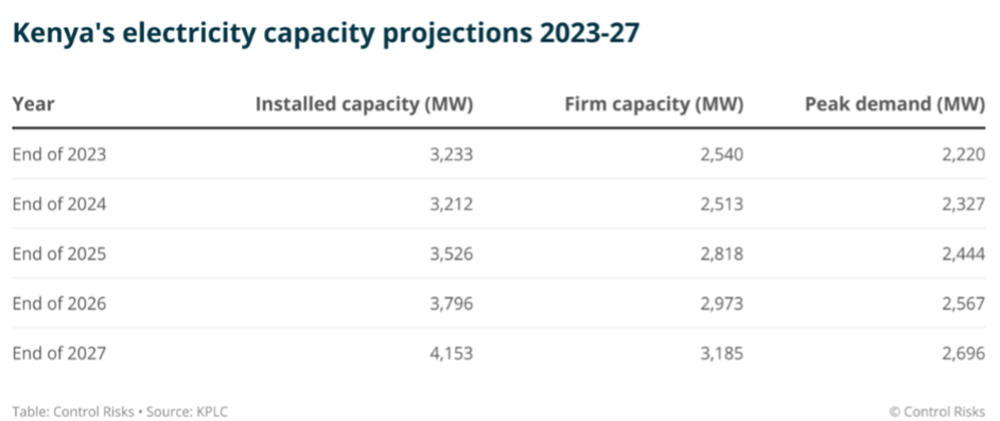

Regarding power generation, Kenya’s current peak demand stands at 2,316 MW and the firm capacity stands at 2,344 MW, way below the recommendation of a 20%-35% reserve margin. This presents a real risk of demand outstripping supply in the near future, with peak demand forecasted to grow to 2,696 MW by 2027; this could require load-shedding if new firm capacity is not on-boarded, as illustrated in the projections below.

To prevent load-shedding, the Kenya Power and Lighting Company (KPLC) has earmarked projects to onboard an additional 857 MW of firm capacity to maintain stability in the electricity supply. However, this brings into focus the prolonged moratorium on new power purchase agreements (PPAs). The moratorium was imposed in 2018 over high power costs, presumably caused by skewed PPAs that favour power producers over consumers. Since 2018, the moratorium has prevented the onboarding of new generation capacity and the renegotiation of PPAs that will be expiring soon.

If Kenya fails to rectify its PPA dilemma, it is a matter of when – not if – Kenya will begin to implement load-shedding. In South Africa, load-shedding is estimated to have cost the economy USD 26.5bn in 2024, emphasising the need to resolve energy infrastructure deficits in Kenya.

Emulating the South African approach to alleviating energy shortfalls

To resolve issues of high energy costs and increased supply risks, the Kenyan legislature has sought solutions modelled on South Africa’s approach to alleviating energy shortfalls through private capital. A November 2024 report by the parliamentary committee on energy acknowledged the need to lift the PPA moratorium and to institute an independent power producer (IPP) procurement programme and IPP office modelled on similar ones in South Africa.

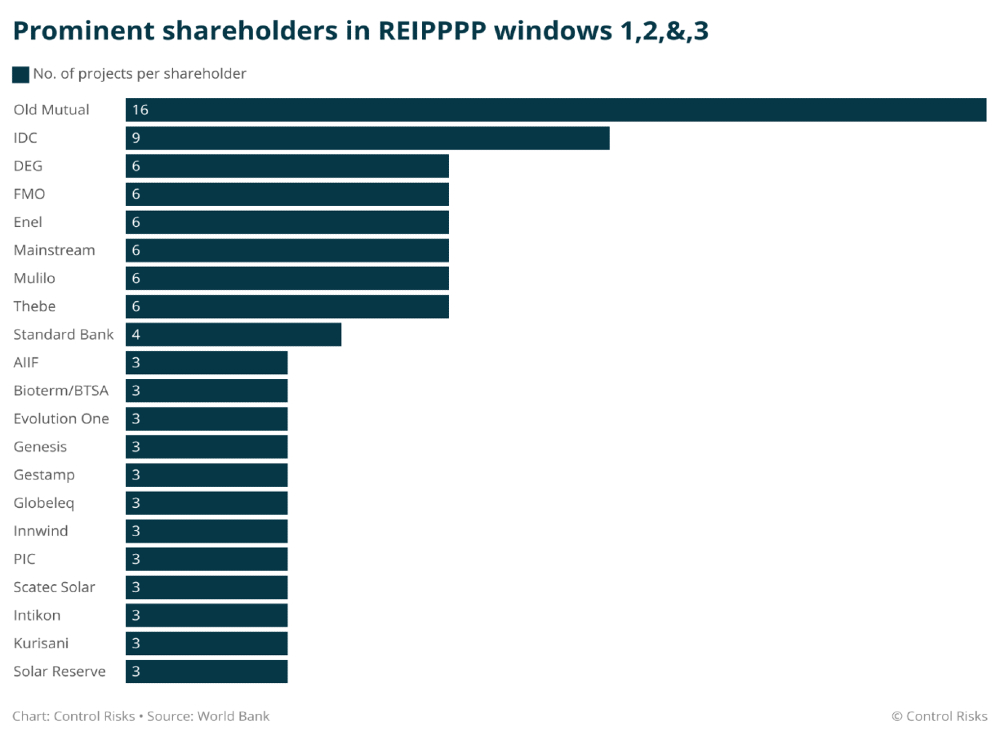

Launched in August 2011, South Africa’s renewable energy power producer programme (REIPPPP) has managed to onboard more than 6,000 MW of renewable energy generation through private-sector investment, despite facing challenges in the more recent past. These challenges stemmed partly from limited political will, which led to bureaucratic delays and the eventual failure of some projects.

South Africa’s part-privatisation of power generation has been championed by domestic capital, with 86% of debt raised within South Africa during the REIPPPP’s first three bid windows. Prominent shareholders include South African financial services institutions, investment corporations, and the Public Investment Corporation, which manages the assets of South Africa’s largest pension fund, the Government Employees’ Pension Fund (GEPF), as illustrated below. The GEPF is also one of the largest investors in the Pan-African Infrastructure Development Fund, a jointly owned fund that invests directly and indirectly in infrastructure.

In Kenya, previous efforts to catalyse pension funds’ involvement have had some success, albeit at a much smaller scale, such as through real estate investment trusts and bonds for road and housing development, totalling USD 113m. Given South Africa has significantly more experience and success crowding in domestic capital, the Kenyan initiative can learn from the challenges they have faced and draw on their successes.

1. Regulatory restrictions inhibit local capital participation

There are regulatory restrictions on the maximum amount that pension funds can allocate to infrastructure projects, which could limit the capacity of these funds to meaningfully participate in large long-term infrastructure projects.

In Kenya, the maximum exposure these funds are permitted to have in infrastructure assets is 10%, which broadly represents about USD 1.5bn of pensions assets in Kenya. This could limit local investor participation in long-term infrastructure projects. By contrast, in South Africa, amendments to the Pension Funds Act in 2022 permit pension funds to directly invest up to 45% of their assets in infrastructure projects.

2. Institutional conflicts and regulatory uncertainty elevate investor risks

Uncertainty and conflicts between related regulatory and institutional frameworks governing project development complicate regulatory processes. This complication has impeded timely and successful project delivery and deterred investors in both South Africa and Kenya.

Certainty and clarity around the institutions and regulations governing these projects need to be enhanced, to minimise regulatory risks and operational delays.

3. Contract and ownership opacity driving integrity and reputational risks

In South Africa, a lack of transparency in contracting has led to bid-rigging allegations, due to perceived bidder preferences and adverse media coverage over the value-for-money of some independent power producer contracts. Criticism has been raised over confidentiality requirements potentially contradicting open governance principles.

In Kenya, a similar lack of transparency has led to the consequential PPA moratorium and a subsequent review of PPAs, which has threatened shortfalls to the country’s energy generation capacity. Both private and public sector stakeholders should consider adequate disclosure frameworks that would serve to dispel any project misconceptions and avert project failures, while still maintaining necessary levels of contract confidentiality.

4. Leveraging credit enhancement facilities to improve project bankability

In South Africa, the provision of credit enhancement instruments, such as government or multilateral finance institution guarantees, have helped increase the attractiveness of energy infrastructure projects. These guarantees help to bridge the gap between actual and perceived risk in projects – a major challenge across the continent – and help to absorb risk on behalf of project lenders, which enhances project bankability. Although the South African Treasury has provided guarantees under the REIPPPP, government guarantees impose an increased burden on the public budget, a key consideration in the Kenyan context amid tightening fiscal spaces.

From a Kenyan perspective, innovative and collaborative private sector credit enhancement facilities are necessary in order to de-risk projects for local capital, without imposing further burdens on the national exchequer.

Hurdles lie ahead for domestic capital pools

Kenya’s ambition to expand the role of domestic capital in infrastructure financing can be bolstered by local pension funds, which witnessed a significant 15% growth between 2023 to 2024. Including a local capital component in a blended finance structure can improve project sustainability through better-balanced foreign exchange risks. It can also attract additional FDI by improving risk perceptions, given that local capital providers likely have more insight into local risk dynamics.

The challenges outlined above will likely undermine local capital mobilisation efforts. Concerted effort by both the private and public sector is necessary to overcome these obstacles. The recently published report by the committee of experts is a great starting point.

Article written by: Ndenga Mulonga