What challenges stem from artisanal mining, and how can formal operators leverage a combination of security and social strategies to mitigate them?

Too often, artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) is viewed solely as a security and operational challenge to manage rather than an ongoing and inherent stakeholder relationship. Although the practice of ASM can straddle the line between legality and criminality, large-scale miners must maintain engaging and enfranchising artisanal miners at the forefront of their approach. This means understanding the socioeconomic and cultural drivers that lead to ASM while building durable relationships with communities to avoid violent unrest.

A complex topic

Invasions of active mine sites, artisanal mining activities in protected areas such as forest reserves, or artisanal mining carried out with the involvement of criminal or other armed groups continue to occur. These phenomena pose significant risks to large-scale operators, nearby communities, and the environment. They range from severe – such as lethal clashes between security forces and illegal miners and strained relations with local communities after accidents on mine sites – to more moderate, such as damage to equipment. Such activity requires a careful response, involving a combination of preventive security measures and proactive community engagement.

Not all ASM is illegal or violent, and the frequent depiction of the practice as unlawful undermines effective responses to it. Examples of ASM include mining by local communities in formal artisanal mining concessions or in areas where it is not explicitly banned. Many communities will see these activities as legitimate, especially if carried out with the support of traditional authorities, even if the central government may not formally license them. Such practices are informal rather than illegal and should be managed differently than practices that are. However, the often-blanket framing of ASM as illegal impedes operators’ ability to constructively manage and help mitigate some of the risks associated with such practices.

A persistent challenge

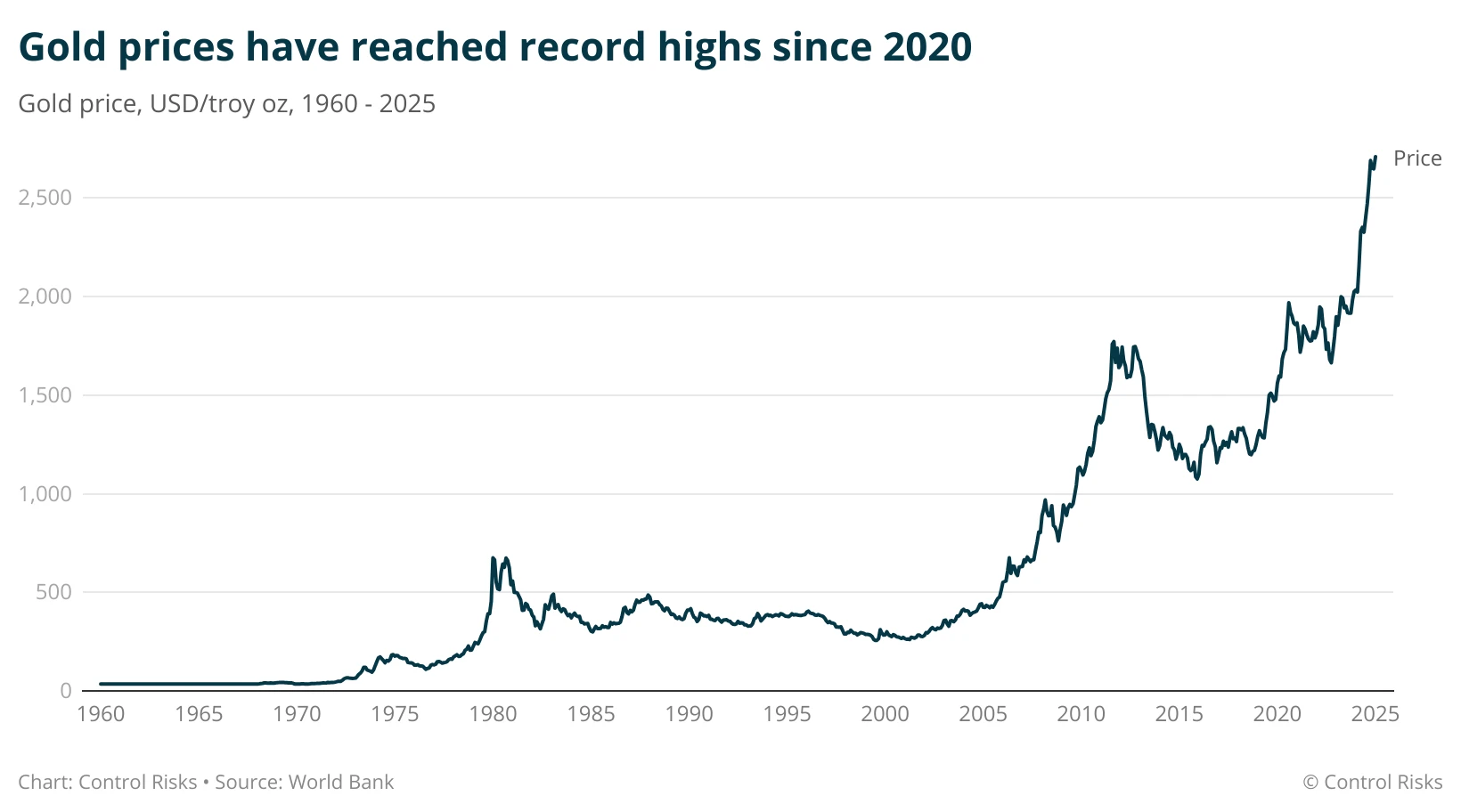

Illegal ASM will not go anywhere anytime soon. In many parts of Africa, ASM is often the most lucrative activity for those with few sources of legitimate employment. It is also far more lucrative than formal employment at a large-scale mine or a formalised mining cooperative, where miners’ profits are taxed and must meet minimum health and safety standards. A BBC investigation in November 2024 reported that an illegal miner in South Africa could earn between USD 15,500 and USD 22,000 annually compared with the USD 2,700 he could earn at a formal mine site. High prices for gold and other precious metals further fuel the growing temptation to engage in illegal mining.

There are also practical drivers encouraging illegal ASM. Obtaining a formal artisanal mining licence is often a complicated process. It typically involves dealing with central government authorities, slow bureaucracies, or institutionalised corruption. Even when issued, it can require steep upfront payments or last for short periods, with no discernible benefits for the applicant.

Many begin mining without waiting for approval from the central government or avoid seeking it altogether. Sometimes, such permits cannot be obtained at all: Ghana banned small-scale mining between 2017 and 2018, and South Africa’s strict mining laws make mining permits almost impossible to obtain for small-scale or informal miners who might otherwise seek approval.

Responsible security: still part of the solution

Security remains key for many large-scale mining companies facing growing illegal mining activities within or near their concessions. Many mining companies in Africa operate in remote locations with little prospect for emergency support, meaning they must rely on on-site support—often a mix of private contractors and government security officials. Many miners in the region also operate where they are confronted with other severe security threats, such as violent crime or militancy. They must maintain a security posture that allows them to manage these threats.

The blurred lines between community-based informal mining and illegal mining complicate this approach. Companies must balance community engagement and the potential security implications it could prompt. When tensions escalate with local communities over employment, environmental impact, relocation, or land rights, they can swiftly turn from a community relations problem into a security problem. This makes a robust security architecture inevitable.

However, there is a risk that this approach alienates communities further, especially with the development of increasingly sophisticated security solutions. For example, many companies are not only adopting more guards and higher fences; they are using AI to identify or predict illegal mining sites from satellite imagery or drones and sensors to monitor concessions in real time. While this improves a company’s ability to mitigate high-severity incidents, it also threatens to incubate resentment among local communities and feelings of physical and economic isolation.

Social engagement for the long term

It is paramount that formal operators implement a robust security response alongside a sustainable social engagement strategy. Engaging with informal miners is often one of the most effective ways of maintaining a social licence to operate, mainly when there are clear opportunities for win-win collaboration – such as providing artisanal miners access to idle or economically unviable parts of a concession or allowing them to go through tailings. Operators can coexist rather than compete with informal artisanal miners by looking beyond purely security-focused responses. This reduces the likelihood of confrontation and can strengthen relationships with local communities, improving overall security.

It can be challenging for large-scale operators to distinguish between legitimate informal miners and opportunistic criminal groups that pose a severe threat. This distinction is crucial and ultimately determines whether engagement is a viable strategy. It also determines what type of support should be provided to which actors.

Mining companies usually already have a strong understanding of local stakeholders, but this does not always consider informal miners. What counts as an effective and appropriate community engagement strategy—the use of community forums or community liaison intermediaries, identifying what needs to be discussed and how often—will differ from site to site. However, ensuring that informal miners are represented will include them in the solution.

Our recommendations

- Increase stakeholder involvement. Involve affected community stakeholders in discussions about ASM management. By soliciting their input in designing the response—such as what forms of engagement are most effective or what type of support to informal miners is most needed—operators can ensure greater buy-in from local traditional authorities and host communities. Informing them about new security measures with a potential human rights impact can help prevent future conflict or disputes.

- Provide technical assistance. Leverage large-scale miners’ technical expertise and resources to support improved health and safety practices, such as removing mercury from artisanal gold mining, providing training, or sharing geological mapping. Operators could also provide microcredit to support equipment purchasing or funding to improve environmental and safety practices.

- Create ASM corridors. Provide access to a commercially unviable site that has been abandoned but remains attractive to artisanal miners. Provisions that the company can reclaim the site should the commodity price reach a certain level are likely to be met with resistance from artisanal miners, so operators should consider this a long-term measure.

- Facilitate purchase schemes. Informal miners often have no means of accessing formal commodity markets and are pushed towards the black market, where they not only receive lower prices but can also fall under the influence of criminal groups. Providing access to legitimate markets can bring them into a better-regulated ecosystem.

- Lobby for ASM formalisation. Large-scale miners are often key investors in African countries. They can use this leverage to encourage the government to remove barriers to formalisation, such as by establishing offices with the power to award licences in smaller cities where they can be more easily accessed.