Saudi Arabia is rapidly emerging as a dealmaking centre and source of investments into Sub-Saharan Africa. This is being driven by an overlap between Riyadh's push for economic diversification and African countries' strategic priorities around food security, critical minerals and clean energy.

How is the kingdom steering this emerging dynamic and where are the areas of most opportunity?

Drive for economic diversification prompts a reappraisal

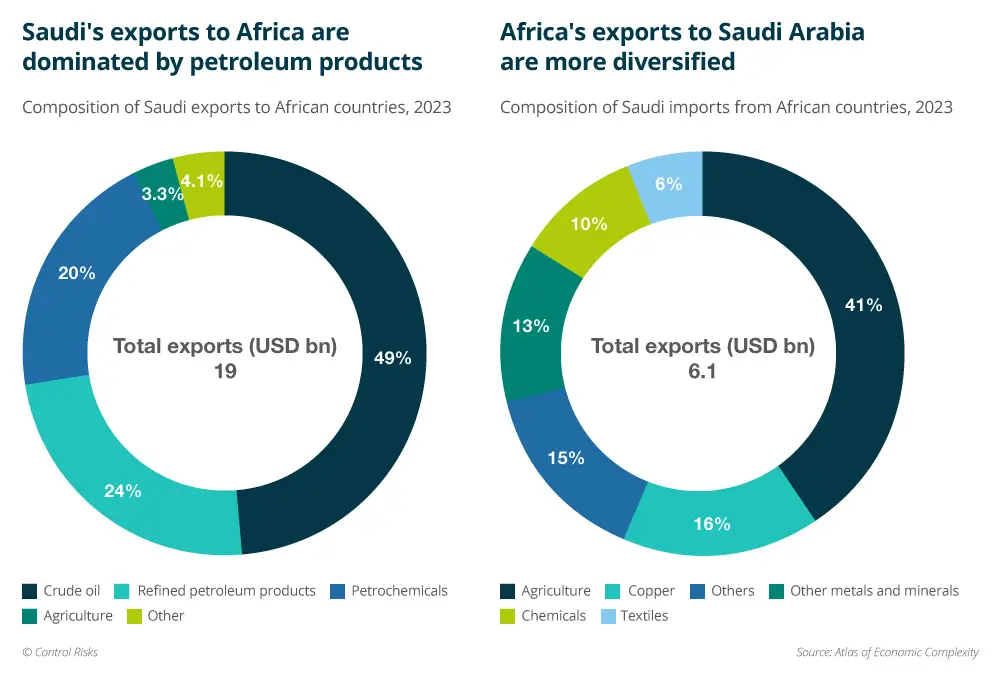

Saudi Arabia’s relationship with Africa has begun to change dramatically, with the continent now the target of Saudi investment rather than just aid distribution. Historically, Saudi Arabia saw the continent as a source of pilgrims and a destination for aid: since 1975, the Saudi Fund for Development (SFD) government agency has provided at least USD 10.7bn to projects in 46 countries in Africa. Saudi exports to the continent (worth USD 19bn in 2023) have historically been dominated by crude, petroleum products and petrochemicals (90% of the total).Saudi Arabia began to see the African continent in a new light as the implementation of its Vision 2030 economic diversification plan, launched in 2017, has gathered momentum. However, diplomatic, political and economic bridge-building is still in its infancy.

Saudi public and private companies are missing out on potential investment opportunities in Africa’s fast-growing economies, and a lack of strategic vision for its relationship with Africa puts the kingdom at a disadvantage relative to other more active regional players, including the UAE and Turkiye.

Aware of these disadvantages, the Saudia government has been working to create pathways for investment and communication. In November 2023, the Saudi-Africa summit in Riyadh marked the kingdom’s first foray into meaningful government-to-government engagement with 50 countries on the continent. In 2024, the Public Investment Fund (PIF, sovereign wealth fund) held an edition of its flagship investment conference series, Future Investment Initiative (FII), focused entirely on investment in Africa, and the 2024 Future Minerals Forum (FMF) hosted the creation of the Africa Minerals Strategy Group.

At a time when other funding sources are drying up, African countries have responded positively to these overtures. Nigeria and South Africa, for example, have both actively courted Saudi investors with high-profile visits, viewing Riyadh as a source of big-ticket, fast-moving finance, especially for infrastructure projects that are increasingly struggling to attract Western or Chinese capital. Nigerian President Bola Tinubu in November 2024 visited Riyadh to seek a USD 5bn oil-backed loan (which would be the largest to date), having formed a Nigeria-Saudi Arabia Business Council the previous year.

Riyadh’s Africa ambitions

Saudi Arabia does not have a single vision for its strategic relationship with the continent. But this does not necessarily mean less engagement. In largely delegating Africa deal-making to individual ministers, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has facilitated a whole-of-government effort to increase engagement on multiple fronts.

This approach increases the likelihood of plans or Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) materialising into tangible bilateral economic activity, even with such a top-down policymaking structure in government. It has also encouraged privately owned Saudi companies to investigate and pursue opportunities in Africa that they would have previously shied away from.

Saudi Arabian and African strategic interests overlap in key areas, all of which are vital components of the kingdom’s Vision 2030 plan:

- Food security: Only 1.6% of Saudi territory is suitable for arable farming. Securing preferential access to international food supply chains is a key tenet of the food security strategy. The King Abdullah Initiative to invest in foreign arable land began in 2009, but the PIF-owned Saudi Agricultural and Livestock Investment Company (SALIC) has intensified its foreign investments in agriculture since 2020, culminating in its February 2025 investment of USD 1.8bn to increase its stake in Olam Agri – a leading food and feed producer in West Africa – to a controlling 80% stake.

- Critical minerals: The government is prioritising developing its domestic mining industry to exploit what it believes is a USD 2.5trn industry. Africa will form a core part of the ‘Super Region’ in which Saudi Arabia wants to position itself as a facilitator of investment, continental knowledge-sharing and wealth generation across Africa, MENA and Asia. Saudi investors prefer to take minority, non-active stakes in mining companies in Africa for now. This supports capacity- and knowledge-building for Saudi firms in the sector, with limited prospects of active management over the next three years, though this will change as the domestic mining sector develops.

- Energy security: Investing in and developing green energy in Africa allows Saudi Arabia to create a new strand of energy diplomacy while developing experience in the sector as an international operator across the energy value chain – a new set of skills and knowledge for a pivotal oil producer navigating a Net Zero future. National champion ACWA Power has been central to the Saudi government’s efforts so far, rapidly rising to be the largest private renewable energy investor in Africa, with more than USD 7bn invested.

- Logistics and connectivity: Saudi Arabia has deployed a more pared-back strategy to build connectivity than the UAE government-owned logistics firms DP World and Abu Dhabi Ports due to limited capacity and a less ambitious vision. That said, there are early indications of Saudi players seeking to take positions in port concessions, and Saudi Arabia in 2023 signed an MoU with pan-African lender Africa Finance Corporation (AFC) to jointly fund infrastructure projects across the region.

These four priority areas will dictate where and how public and private Saudi firms invest in Africa over the next five-to-ten years. Other sectors still draw greater interest – for example in semi-skilled or skilled manufacturing, food and raw materials processing, or real estate. The government’s priority is to build out that capacity in the kingdom itself, a project that is integral to Saudi’s long-term economic stability and political survival.

Government financing for investments has been mainly directed through national champions such as the PIF, ACWA Power or national oil company Aramco. Their close affiliation with the state will offer them some form of diplomatic cover. Following bilateral talks in Riyadh in late 2024, ACWA Power was able to renegotiate a water desalination project that had been cancelled by the new government of Senegal.

Private family-owned conglomerates are taking an increasing interest in opportunities in Africa, as well, and these are also linked to Vision 2030 plans. The AFC MoU suggests an emerging interest in providing capital to lenders with greater experience of deploying it in the region – making Saudi players potential co-financiers for several other investment firms.

Soft power plans

The kingdom does not have the diplomatic and political ties of Qatar or the UAE to be able to shape Africa’s political environment, and neither does it wish to. Its diplomatic engagement in the region has so far been more cautious and focused on stabilisation, especially in the Horn of Africa; for example, it has made an attempt, still largely embryonic, to establish multilateral architecture across the Red Sea through the Council of Arab and African Coastal States of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (RSGA).

Riyadh has also refrained from intervening as a conflict mediator, except in Sudan, where it has led the main mediation track between the two warring parties, with limited success. But it does benefit from being perceived as a neutral party (unlike other Middle East and North Africa states and its Gulf Arab neighbours especially). For Muslim-majority African nations, it remains highly influential.

Saudi’s leadership of OPEC will also continue to colour its engagements on the West African coast, as oil exporters weigh the benefits of Saudi-led quotas against lost barrels. Angola’s 2023 decision to quit OPEC after a quota cut it blamed on Riyadh crystallised concerns over Saudi's dominance over African production policy. Other OPEC members Nigeria, Gabon, Congo and Equatorial Guinea have all accepted lower ceilings and are not considering walking out: they are limited in how much oil they can produce, meaning they are happy to accept lower quotas.

Bigger cheques, bigger scrutiny

With the pace of both diplomatic and private sector engagements rapidly increasing, steady deal flows in minerals, renewables and agrifood are likely in the coming years. This will consolidate the kingdom’s position as an important partner and source of capital – one valued for its speed and scale. Saudi Arabia will likely continue to avoid entanglements in conflicts or divisive politics and portray itself as a stabilising influence.

But with larger cheques come larger expectations – from African governments seeking balanced deals, from local communities demanding greater transparency, and from other partners wary of being crowded out of projects. Like other Gulf investors, Saudi investors are likely to see external scrutiny of their operations significantly grow in the coming years, in line with their influence.

Awareness of political, country and economic risks underpin your organisation’s ability to protect value and mitigate shocks. Learn how we can support your organisation.