This article is based on content originally published on our partner platform Seerist, the augmented analytics solution for threat and risk intelligence professionals.

Amid US and Israeli air strikes across Iran in June, Tehran re-issued long-standing threats to close the Strait of Hormuz – a geostrategic chokepoint due to its being the only route into and out of the Middle East Gulf.

How would a Hormuz closure impact regional energy exports, imports and geopolitics?

- Most Middle East Gulf littoral exporters are still reliant on the strait – but 50% of exported crude oil barrels have alternative transit routes, with more under development, suppressing potential price impacts of a strait closure on global markets.

- This reduces the impact globally and in the region of any future strait closure relative to now; however, Iran is also building resiliency, making strait closure a more viable tactic for Tehran to resort to in any future regional conflict.

- However, Iran would still need to be in a desperate position to close Hormuz as the impact of doing so would still be significant to both it and neighboring economies.

- If the strait was deemed unpassable, at least 20% of the global liquified natural gas (LNG) export supply would be locked in the Gulf, while severe disruption to containerised and bulk shipping would dramatically impact the supply of day-to-day consumer goods and food in all littoral Gulf states.

Lowering threshold

An attempted closure of the strait by Iran would be an act of significant economic self-harm, would tarnish relatively good diplomatic relations with the Gulf Arab states and would provoke a major US military response.

Iran's largest export terminal is on Kharg Island, in the northern Gulf, from which around 90% of Iran’s crude is exported. That is reliant on tankers being able to transit the strait. Closing the strait would cut current revenues for the Iranian government by 35%.

During June Israel-Iran war, we assessed that Iran would only undertake action to close the strait if it felt under existential threat. Undermining Gulf Arab neighbours would be a way to avoid complete defeat and potential regime change.

In the event, Tehran did not reach for an attempted Strait of Hormuz shutdown following the US’s targeting of three Iranian nuclear facilities on 22 June. Instead, it conducted a calibrated attack on the US military base at al-Udeid (Qatar), and reportedly informed Qatar and the US beforehand.

Before attempting a Hormuz shutdown in any similar conflict scenario in the future, Iran has several options that it would likely deploy first, including attacks on US bases and naval assets as well as Guld Arab oil production facilities.

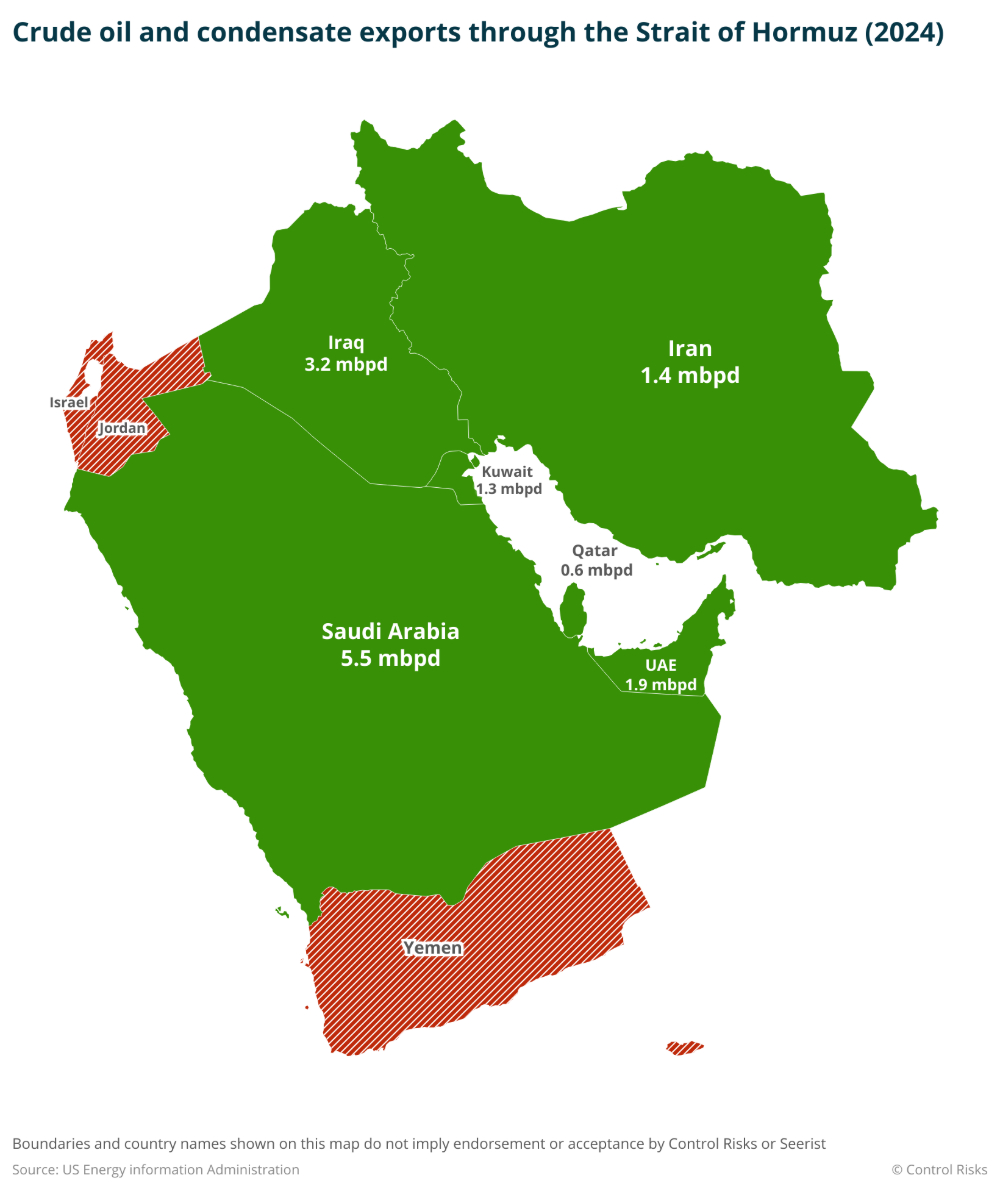

Iran is not the only country that would be affected by a shutdown. The Gulf Arab states that produce crude oil overwhelmingly rely on the waterway. Total flows of crude oil, condensates and refined petroleum products from the Gulf account for one in every five barrels consumed globally each day.

Global consumption is set to average 103.5m barrels per day (bpd) in 2025, rising to 105m bpd in 2026, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). Saudi Arabia is the single largest exporter, sending an estimated 5.5m bpd through the waterway to predominantly Asian export markets.

Some of the Gulf states, including Iran, are already acting to lower their reliance on the strait. This, along with the unprecedented attack on al-Udeid, means a future decision by Iran to close the strait would be an easier calculation.

In Iran, a project is under way to develop a 1m bpd export facility at Jask, south of the Strait of Hormuz, that circumvents the chokepoint. The terminal at Jask is due to come online in the next nine months, with a capacity of 1m bpd once complete. This will create an option to reroute most of Iran’s approximately 1.4m bpd of exports, reducing the self-inflicted impact of Iran using oil as a weapon and so reduces the threshold of deliberation for Iran to use a Hormuz closure as a tactic to pressure other regional actors in a future conflict.

Impact beyond Iran

Saudi Arabia and the UAE

Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s oil economies would be able to avoid the worst of any attempted Strait of Hormuz closure by redirecting crude oil flows, but they would not escape unscathed, finding their refined products and LNG balances affected.

Still, of all the countries that use the waterway, only Saudi Arabia and the UAE have alternative export routes: the kingdom has the 5m bpd East-West Pipeline, and the UAE has the 1.5m bpd Habshan-Fujairah pipeline (also known as “ADCOP”) servicing onshore extracted crude oil.

With estimates of 10%-35% of the East-West Pipeline in use in June 2025, Saudi Arabia would be the only country able to ensure most of its exports could remain accessible in the event of a conflict that leads to the strait’s closure – even if tankers would need to reroute to the Red Sea from the Gulf to get to buyers.

With its current utilisation rate estimated at 73%, the Habshan-Fujairah pipeline handles most of the UAE’s exports (in recent months UAE national energy company Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) has also been prioritising exports of its Murban blend, which are produced at the eponymous onshore field in Habshan) – but any disruption to the strait would prevent the movement of off shore-produced crude volumes.

The UAE has a second 1.5m bpd pipeline under construction, from Ruwais to Fujairah, which is due to be operational in 2027 and which – combined with the Habshan-Fujairah pipeline – would guarantee capacity for all the UAE’s exports of approximately 2m bpd by creating an option for off taking off shore-produced volumes.

Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and Iraq

Many of the smaller Gulf Arab states would find their exports trapped inside the Gulf. Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and Iraq are entirely reliant on the strait for all their exports.

Iraq – the region’s second-largest producer – has a 450,000 bpd pipeline via Kurdistan to Turkiye, but political disputes closed this route in March 2023. In the absence of political will, an imminent resolution to this closure is unlikely, and the pipeline will remain vulnerable to spats between the federal and Kurdistan Region governments in the future. The three Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states have no stated intentions to develop their own alternatives, leaving them vulnerable to future disruption. Iraq's prospective alternative export routes are unlikely to come to fruition within the next three-to-five years at least.

Qatar’s part ownership alongside Iran of the world’s largest natural gas field (known in Qatar as the North Field and in Iran as South Pars) and its decision to become an LNG exporter have generated its extraordinary wealth. Qatar holds the world’s third-largest natural gas reserves and is the second-largest exporter of LNG globally, supplying 20% of the market.

All of Qatar’s LNG exports are transported by sea. It has a single short-distance export option: the Dolphin pipeline of 2.6bn cubic feet, which connects Qatar with the UAE but goes no further. The UAE’s own existing LNG export facility at Das Island would be cut off in the event of a Hormuz closure, and ADNOC chose Ruwais over Fujairah for its export terminal expansion project in 2023, meaning all its LNG export capacity would be trapped inside the Gulf.

As the UAE’s LNG exports increase and Qatar brings online its expansion of the North Field, this will increase the potential for an even larger share of global export market demand to be trapped in the event of the strait’s closure.

Where will energy impacts be most visible?

Asian markets take the overwhelming majority of energy exports from Gulf littoral states – whether crude oil, refined products or natural gas – and would experience a meaningful supply shock in the event of the strait’s closure. There would be some impact on benchmark oil prices, but whether that impact is a lasting significant price shock is entirely dependent on other exogenous factors: global economic activity and the amount of oil in floating storage and national reserves that could be activated.

According to the latest complete data from 2023, the US only imports 10% of its daily imports of 8.51m bpd from Gulf states – 90% of that from Saudi Arabia and Iraq. The federal government could source barrels from elsewhere in an emergency, including its Strategic Reserve – so closing the waterway is a less effective form of economic and political leverage specifically targeting the US in any conflict.

The sole means Iran or any other state has of influencing a US president’s response to a regional conflict is through sharply increasing global benchmark oil prices – but it is extremely difficult to predict accurately how the market would respond. With approximately 50% of regional export volumes already able to be redirected through alternative means by the first- and third-largest Gulf Arab producers – Saudi Arabia and the UAE – it is plausible these workarounds could suppress any price response in markets.

The cost – both literal and symbolic – to Europe and the US of a Hormuz closure has dramatically lowered over time; there is no risk of the same shock as during the 1973 oil embargo. Ultimately, much like 1973, cutting off energy supplies from the region would in fact hurt the countries of the region the most. But that alone will not be enough to stop it remaining on the table as a tactic in war.

Impact on imports

The lower cost of a shutdown from an energy perspective remains counterbalanced by the reliance of Iran and other littoral states on the strait for imports, including foodstuffs – which remains a strategic vulnerability for all.

Despite its domestic refining capacity, Tehran relies on imports of refined products – petrol, diesel and other fuels – all of which are fundamental to any country in wartime. Iran’s relative agricultural self-sufficiency reduces the immediate impact of any self-imposed blockade, but its larger cargo-handling facility at Bandar Abbas (which lies on the strait) would still be cut off. Unlike how Jask will compensate for crude exports, the underdeveloped port of Chabahar on the Gulf of Oman cannot compensate for Bandar Abbas’ volume.

Likewise, the Gulf states import refined products and often LNG to make up their energy balance.

Beyond energy, a shutdown attempt would severely disrupt container and bulk shipping routes – halting the movement of everything from consumer goods and grains to steel for construction projects. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are less vulnerable to food insecurity prompted by a prolonged shutdown, owing to existing or planned large grain reserves on their Red Sea and Gulf of Oman coasts, respectively, and accompanying bulk handling ports that would continue operating.

However, overland transport by rail or road from those coasts to Gulf populations cannot entirely replace the capacity provided by shipping. Meanwhile, officials from Qatar, Kuwait and Iraq all state that their respective countries have or are developing around six months’ worth of food reserves, but due to a lack of non-Gulf ports, they would face a more acute situation for resupplying any dwindled reserves in the event of a prolonged shutdown.

A complete halt? Unlikely

An attempted Iranian blockade is unlikely to bring maritime traffic to a complete halt – some shipowners and operators would almost certainly seek to run the gauntlet. While major shipping lines would divert away from the strait, smaller owners would take the opportunity for business – as seen on the western Arabian Peninsula since the Houthis’ Red Sea maritime attacks began in November 2023.

The largest ships, owned by the largest lines, would likely be replaced by smaller “feeder” vessels seeking to fill the gap – meaning overall tonnage passing through the strait would not be wiped out.

The Middle East is in its most serious geopolitical crisis for decades. Keep informed on the business impacts, and what developments may mean for your organisation with our Middle East Monitor.