This article is based on content originally published on our partner platform Seerist, the augmented analytics solution for threat and risk intelligence professionals.

In light of the US’s issuance of General Licence 25 on 23 May, we provide an update to the analysis at the end of this piece.

On 13 May, US President Donald Trump announced that he would order the “cessation of sanctions against Syria” while speaking at the Saudi-US Investment Forum. What are the implications for Syria and the prospects for international business there?

- The announcement signals a significant shift in the US’s decades-long policy of economic pressure on Syria, with a range of immediate implications – particularly in the financing space.

- It reinforces a broader trend of easing sanctions regimes that began with the US issuing exemptions in January; EU foreign ministers on 20 May agreed plans to lift remaining economic sanctions.

- Significant uncertainty will persist over the exact mechanisms and timelines for the lifting of US sanctions – sustaining long-term compliance and investment risks.

- Numerous operational, security, institutional, integrity and reputational risks will also persist and continue to pose challenges to any expansion of business activity for most private sector actors.

Sanctions regimes

Ending sanctions would require waiving, terminating and repealing an array of sanctions imposed by multiple US administrations over several decades

The US first introduced sanctions against Syria in 1979 when it designated it as a state sponsor of terrorism. In the 1990s and 2000s, it imposed successive rounds of sanctions in response to Syria’s occupation of Lebanon (1976-2005), Weapons of Mass Destruction activities and destabilisation of Iraq. After the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, US sanctions expanded significantly in response to political repression, human rights abuses, chemical weapons use, corruption, and drug trafficking and targeted leading political and business figures as well as key economic sectors

In 2019, after several years of debate, the US enacted the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act, which authorises secondary sanctions against foreign companies that conduct transactions with the Syrian government or military. On 23 December 2024, this law was extended for five years until 2029. In addition to Syria-specific measures, many individuals and entities in Syria are sanctioned under sanctions programmes related to terrorism, corruption, non-proliferation, organised crime, human rights, and third countries like Iraq, Iran, and North Korea.

Syria also faces UN Security Council sanctions, which member states are required to implement. The UN sanctions relate to the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in 2005 and to terrorist organisations Islamic State (IS) and al-Qaida, under which interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa remains sanctioned under his nom de guerre Abu Mohammed al-Jawlani. (In December 2024, the US removed a long-standing USD 10m counterterrorism bounty on Sharaa.) Syria also faces similar sanctions regimes from the EU and its member states as well as a range of other Western countries, including the UK, Norway and Australia.

Loosening and easing

Since Sharaa rose to power in December 2024, there have been calls to alleviate international sanctions to aid Syria’s reconstruction and stabilisation. The US introduced General Licence 24 on 6 January to exempt the provision of electricity, energy, water and sanitation from sanctions, and allow previously prohibited transactions with Syria’s “governing institutions” for the purpose of activities in the sectors above as well as for remittances, including with the Syrian central bank.

Meanwhile, the EU suspended select restrictive measures on 24 February with a view to enable activities and transactions in the humanitarian, energy, construction and transport sectors, including by removing five entities from an asset freeze list. (It is expected to lift remaining economic measures after EU foreign ministers on 20 May reached agreement to do so.) The UK moved in sync with the EU and even went further on 24 April, lifting sanctions on the new Syrian Ministry of Defence.

Sanctions timelines

Trump’s statement on 13 May, while decisive, lacked clarity about the mechanisms and timeline by which the US will lift sanctions. Removing sanctions designed to isolate the regime of former president Bashar al-Assad and his government would seem a logical step, while Trump probably does not intend to remove sanctions that relate to Iran, designated terrorist groups or individuals associated with the former regime.

Crucially, the US administration cannot unilaterally terminate UN sanctions or repeal statutory sanctions, such as the Ceasar Act, without Congress approval. Some US lawmakers likely intend to keep sanctions in place until the Syrian government demonstrates democratic commitment; others will likely oppose lifting restrictions on individuals and entities, including Sharaa, with past linkages to designated terrorist groups.

Therefore, it appears unlikely that all US sanctions will be lifted in full or immediately. (Notably, Trump chose to renew Executive Order 13338 of 2004, which imposes sanctions on the Government of Syria, on 7 May, less than a week before his announcement.) Instead, the administration will likely ease sanctions in a staggered manner. Trump will likely repeal – or let lapse – some Executive Orders that target the Syrian government and its key principals, waiving Ceasar Act provisions for 180 days by certifying that the Syrian authorities are meeting certain conditions relating to human rights and good governance, among other requirements.

Such measures will signal US intent to pare back sanctions over the long-term. However, much of the relief will initially be temporary and partial, rather than immediate, complete and permanent repeals. Western companies looking to operate in Syria will need to retain robust sanctions compliance systems. The temporary nature of waivers and the resulting potential for snap backs will continue to drive long-term investment risks, especially considering enduring uncertainty regarding the Syrian authorities’ intent and capacity to put in place an inclusive and pluralistic mode of governance.

Opportunities for Western entities will likely remain focused on humanitarian-focused trade over the coming months, including in sectors like food, energy, medical items and telecoms. Conversely, long-term investments will likely be dominated by regional actors with a degree of insulation from US sanctions, such as Türkiye (and to a lesser degree European entities) and state-owned entities, particularly in the Gulf – provided they can secure diplomatic assurances about waivers and sanctions non-enforcement from the US.

Other obstacles will remain

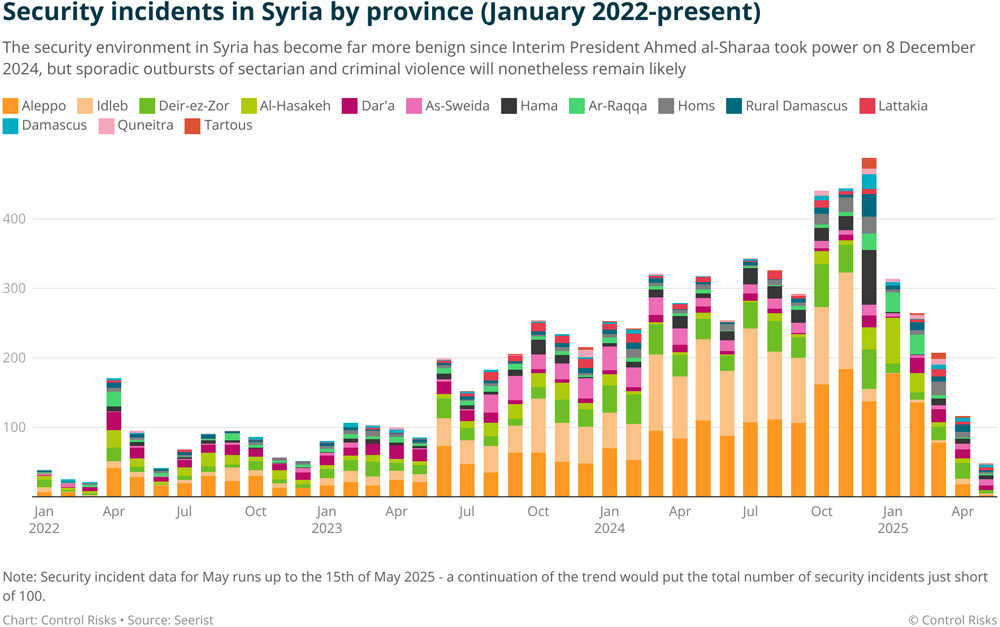

The anticipated easing of sanctions will have a stabilising effect on Syria. In particular, reintegrating Syria into international financial systems will help unlock funding by bilateral backers and multilateral lenders, including to support government activities, such as an expected Qatari disbursement USD 29m over three months to fund civil service pay. An influx of funds into the country will help drive economic recovery and legitimise Sharaa’s governance. However, funds will be no panacea to ongoing deep societal rifts and competing demands on the authorities. Occasional outbursts of violence as seen against Alawite communities in March and Druze areas near Damascus in early May will remain likely, sustaining a baseline of security threats.

The business environment will remain extremely challenging. Basic infrastructure will take years to restore fully, if only due to the sheer scale of destruction over more than a decade of civil war. Many foreign economic players will have acute integrity and reputational concerns concerning dealings with authorities that partially hail from Islamist extremist movements and local business entities whose pasts and ultimate beneficial ownership will often be difficult to ascertain. Robust institutional, legal and regulatory frameworks will remain largely non-existent for the coming months at least. Consequently, entities looking to enter the Syrian market, in addition to assessing ongoing compliance risks, will need to review the whole universe of country risks carefully.

Addendum: analysis of the US’s partial lifting of sanctions (as of 27 May)

The US Treasury Department on 23 May introduced General Licence 25 and exemptions to the Patriot Act targeting the Commercial Bank of Syria. On the same day, Secretary of State Marco Rubio issued a 180-day waiver for the Ceasar Act sanctions. Together, the measures provide broadly framed exemptions to the US’s Syria sanctions regime that will facilitate commercial and humanitarian engagements with Syria, particularly in the power, energy, water, sanitation and wider humanitarian sectors. They also constitute a first step towards reintegrating Syria into international financial systems; although streamlined international transfers will likely remain unavailable for at least several weeks, possibly a few months, as Syrian banks are yet to rejoin the SWIFT international financial messaging system and as anti-money laundering and terrorism financing concerns will endure.

Rubio also hinted at the conditionality imposed on any definitive repeals. Rubio’s press statement emphasised expectations of “prompt action by the Syrian government on important policy priorities”. With the Ceasar Act waiver bound in time and persistent uncertainty over the Syrian authorities’ ability to satisfy existing and any potential future US demands, economic engagement with Syria by entities exposed to US sanctions enforcement is likely to remain focused on ad-hoc trade rather than long-term investment. Moreover, compliance costs will remain elevated, given the targeted nature of exemptions under General License 25 as well as ongoing restrictions under other legislative acts that are yet to be waived.