Kenya and Congo (DRC) in recent years have shown mutual desire to deepen their trade and security ties. Amid growing scepticism regarding the performance of the Kenyan-led peacekeeping force in eastern Congo, we assess how relations are likely to evolve in the coming years.

- Kenyan President William Ruto, who took office in September 2022, will struggle to earn the trust of his Congolese counterpart Félix Tshisekedi – likely to secure re-election in December 2023 – complicating further bilateral engagements in the coming years.

- However, Ruto will come under pressure from his allies in the business community and Western partners to follow through with his predecessor (2013-22) Uhuru Kenyatta’s plans to make Congo one of Kenya’s strategic partners.

- Ruto will prioritise economic engagement over security cooperation, especially as he seeks to avoid being pulled into Congo’s security disputes with Rwanda and other regional partners.

- Although this will encourage Congo to explore alternative partners in East Africa, it will continue to prioritise engagements with Kenya to create a more conducive security and operational environment for cross-border trade.

Circumstantial allies

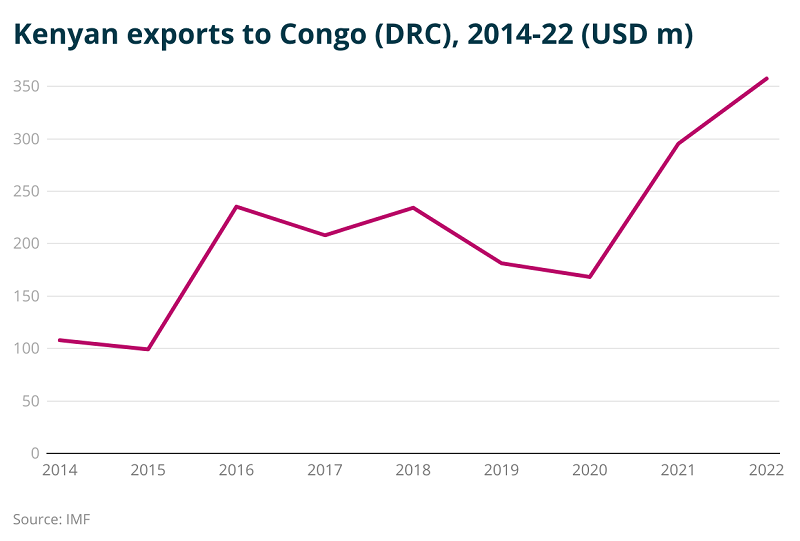

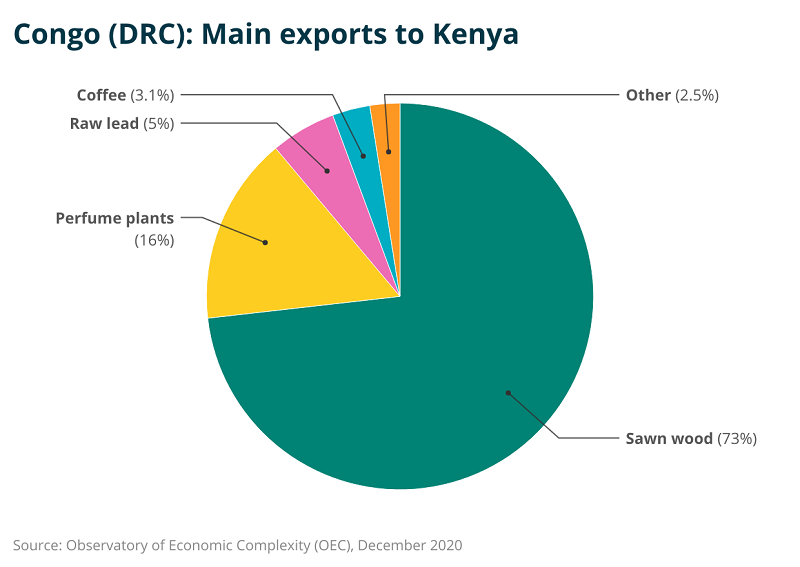

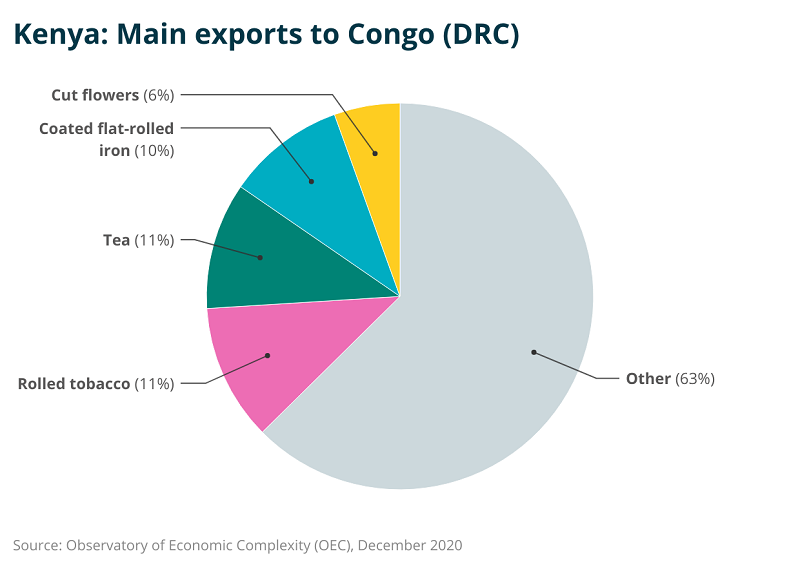

Congo has long been an important export partner for Kenya, particularly because the protracted conflict in Congo has hampered agricultural productivity – and economic activity more generally. Many Kenyan traders have seen this as an opportunity to provide agricultural and manufactured goods to Congolese communities, especially in the east. Meanwhile, eastern Congo, which is somewhat cut off from western Congo and the country’s main port in Matadi, also relies on the Port of Mombasa in Kenya for imports and exports.

Despite this, there had been no real efforts to formalise and facilitate this trade until Tshisekedi took office in 2019. Although the Kenyan government had signed several trade agreements with the former Congolese administration of Joseph Kabila (2001-19), these were haphazard. The two countries made little effort to improve supply chains linking their markets, leaving traders reliant dilapidated road infrastructure.

Engagement has long been complicated by Congo’s complex position in the region, which regularly puts it at loggerheads with many of Kenya’s regional allies, notably Uganda and Rwanda. This has also deterred Kenya from actively participating in regional efforts to mediate between the three countries and restore peace in Congo.

For its part, under Kabila Congo preferred to engage with other regional heavyweights – notably South Africa, whose government has close relations with Kabila. Kabila was particularly frustrated by Kenya’s seeming acquiescence to informal – and often illicit – trade between the two countries, especially amid allegations that some Kenyan government officials benefited from smuggled Congolese minerals under the government of former president Daniel Moi (1978–2002).

However, in recent years Kenya has shown growing desire to better balance the need to preserve relations with Rwanda and Uganda with an acknowledgment that more productive engagements with Congo will help it to achieve its socioeconomic goals. This change of heart has in part been driven by a shift in internal political dynamics in Kenya, notably a rapprochement in 2018 between Kenyatta and veteran opposition leader Raila Odinga. Odinga, who has close relations with Tshisekedi, played a key role in selling Congo’s investment potential to Kenyatta, marking the start of a campaign to make Kenya a strategic partner for Congo. Odinga supported Tshisekedi’s presidential campaign in 2018, facilitating talks with the latter and potential election partners. This earned him the trust of Congolese officials, who are keen to dilute Rwanda’s commercial and security influence in Congo by engaging with Kenya.

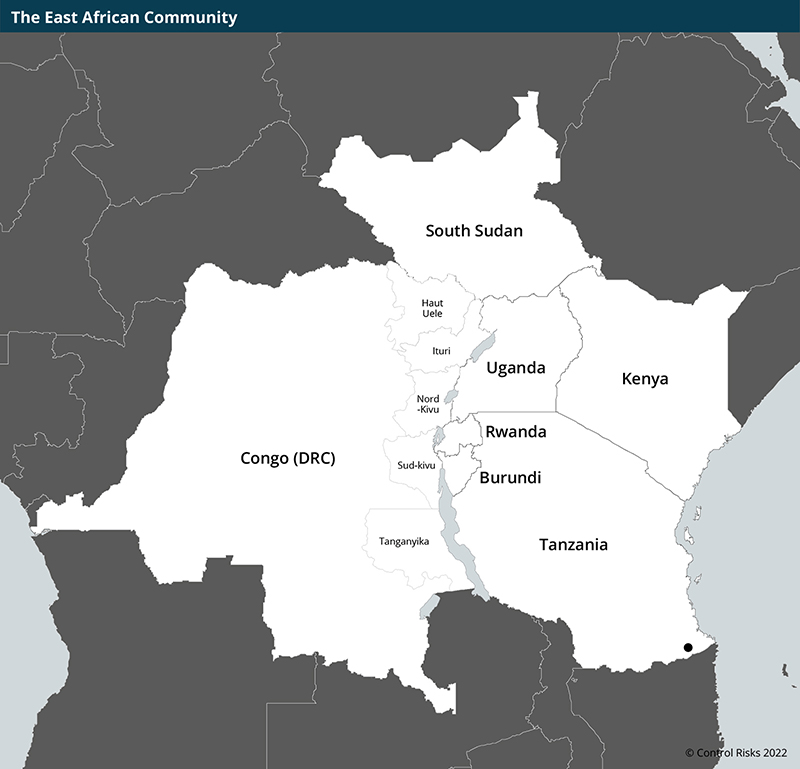

In this context, there has been a significant rapprochement between the two countries since 2019, culminating in Congo’s admission into the East African Community (EAC) regional bloc in March 2022 and the deployment of the East African Community Regional Force (EACRF) led by Kenya in eastern Congo in March 2023. Kenyan investment in Congo has also increased, especially in the financial services sector, and Congo in mid-2022 became the third-largest source of traffic at the Port of Mombasa.

However, although Kenya’s business community remains bullish about opportunities in Congo, Odinga’s loss at the 2022 elections in Kenya has dampened hopes for a further rapprochement. Since Ruto took office, bilateral disagreements have gradually increased. For example, Kenya’s reluctance to upset Rwanda has driven perceptions in eastern Congo among the public and some politicians that its forces – and the EACRF – have acquiesced to the operations of the Rwanda-backed March 23 rebel group. This led to the sudden resignation in April of EACR commander and senior Kenyan army general Maj Gen Jeff Nyagah. Tshisekedi has since been looking to the Southern African Development Community (SADC) for alternative security support. These dynamics have cast doubts over the future of Kenya-Congo relations.

The future of “Project Congo”

Relations will remain complicated under Ruto. However, the president will face heavy domestic and international pressure to continue the rapprochement initiatives initiated by his predecessor.

Domestically, the pressure will come from influential business elites, which are increasingly frustrated by Ruto’s failure to prioritise engagement with Congo. Many of these figures have made sizeable investments in the region in anticipation that Ruto would negotiate preferential treatment for their interests in Congo and are now fearing losses.

For example, the Congolese government in late May announced that it had signed a 25-year deal giving a UAE-based firm special rights over the export of artisanal gold. This prompted concerns from Kenyan businesspeople, who have already invested in gold smelting in Uganda with the expectation that Congolese gold would transit through there, rather than directly to the UAE.

To avoid further setbacks, these figures are likely to embark on an intense lobbying campaign to align Ruto’s policy with their Congo ambitions. This is likely to push Ruto to adopt a less passive stance towards Congo, especially because Kenya is hoping to benefit from Congo’s mineral resources to become a regional hub for mining transactions.

More broadly, Ruto cannot afford to overlook engagement with Congo as he seeks to preserve Kenya’s dominant position in the regional economy. The loss of momentum in Congo-Kenya engagements in recent months has emboldened regional rivals such as Tanzania and to a lesser extent South Africa to woo Tshisekedi away from Kenya.

Tanzania is particularly keen to divert Congolese exports and imports away from the Port of Mombasa and towards its own ports, and in mid-May offered Congo an exclusive cargo transit clearance deal. Ruto will be keen to ensure that Mombasa remains the preferred port for traders in eastern Congo over the coming years. The port is a major source of revenue for Kenya, while Ruto is scrambling to boost revenue collection amid a growing debt-servicing burden.

Meanwhile, Western partners, especially the US, are also keen to foster greater trade and security collaboration between Kenya and Congo. Tshisekedi has increasingly relied on the US to support peace-building initiatives in eastern Congo. However, this has had limited impact given that Rwanda has closer relations with the US. To appease Tshisekedi, the US will continue to look to Kenya to act as a potential buffer between the two countries, hoping that Kenya’s growing military influence in eastern Congo could encourage Rwanda to reduce intervention there.

In this context, Western partners will continue to favour peacebuilding efforts led by Kenya, offering support to the EACRF. This will be another incentive for Ruto to pursue close relations with Tshisekedi as he seeks to preserve longstanding security cooperation with the US. Meanwhile, Kenya will be keen to exploit the US’s desire to dilute China’s influence over Congo’s mining sector to push for US support for Kenyan (and EAC) mining projects in Congo.

In this context, engagement with Congo will remain a priority under Ruto. Ruto is unlikely to pursue this goal as vigorously as his predecessor, not least due to concerns over Tshisekedi’s ties to Odinga, who has become his fiercest critic. Although Ruto appears to realise the importance of strengthening relations with Congo, he will be less open to granting concessions, especially with regard to the nature of Kenyan Defence Force (KDF) intervention in Congo. Ruto has demonstrated an affinity with Uganda President Yoweri Museveni and to a lesser extent Rwanda’s Paul Kagame, and will take special care not to be seen as a threat by these figures. He is thus likely to focus on trade discussions and will view security cooperation as secondary to this.

Congo’s stance

This will make it more difficult for Ruto to earn the trust of Congolese officials, which are increasingly likely to use economic deals as leverage to push for the EACRF and Kenyan army to take a more active role in the fight against the M23 and other militias.

Nonetheless, despite this, and despite his threats to replace the EACRF with a SADC force, Tshisekedi will continue to see Kenya as an important regional ally. First, he will seek Ruto’s support for his re-election campaign ahead of the 20 December elections. More importantly, Congo has only recently recovered from years of regional and international isolation. This means that Tshisekedi will be reluctant to throw away a partnership with Kenya, which retains a dominant position in the regional and diplomatic arena.

Tshisekedi will therefore remain willing to facilitate Kenyan investment in under-developed sectors in Congo such as banking, especially given his desire to boost credit availability for Congolese small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs). Although he will increasingly be open to discussions with alternative regional partners – notably South Africa and Tanzania – he will prioritise engagement with Kenya.

Outlook

Overall, these dynamics bode well for bilateral trade prospects in the coming years. Both countries will remain keen to ease cross-border trade, while Congo’s EAC membership will provide a further platform for Ruto and Tshisekedi to engage on issues such as reducing trade barriers and easing the cross-border movement of people. However, progress will be slow as disagreements between Tshisekedi and Ruto derail some initiatives.

Meanwhile, Kenya’s influence over Congolese security affairs will continue to grow gradually. Ruto’s refusal to directly fight foreign-backed rebel groups will remain a point of contention. However, Tshisekedi will continue to seek to collaborate with Kenya on security issues, given its superior counterinsurgency capabilities.

This also means that Tshisekedi is unlikely to make good on his threats to end the EACRF’s mandate – which lapses in September. Kenya will increasingly offer technical support to the Congolese security forces to assuage concerns over its apparent failure to make progress against the M23. This will boost Tshisekedi’s efforts to improve the capabilities of the Congolese army, potentially enabling him to better navigate the volatile security situation in eastern Congo over the coming years.