Corruption, money laundering, ESG and sanctions exposure are common priorities when embarking on ventures in emerging markets, sometimes at the expense of risks regarding terrorism financing.

Terrorism financing risks are often associated with hard-to-detect, lower value transactions between individuals, and relevant only for financial institutions in transaction monitoring. In sub-Saharan Africa, for any form of high value investment, this is not the case. In contrast to the Middle East, where Islamic State (IS) has lost influence in northern Syria and Iraq, terrorist groups are active and growing in several areas in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in the Sahel. Non-state actors in these locations use a range of methods to raise funds and conduct illicit operations.

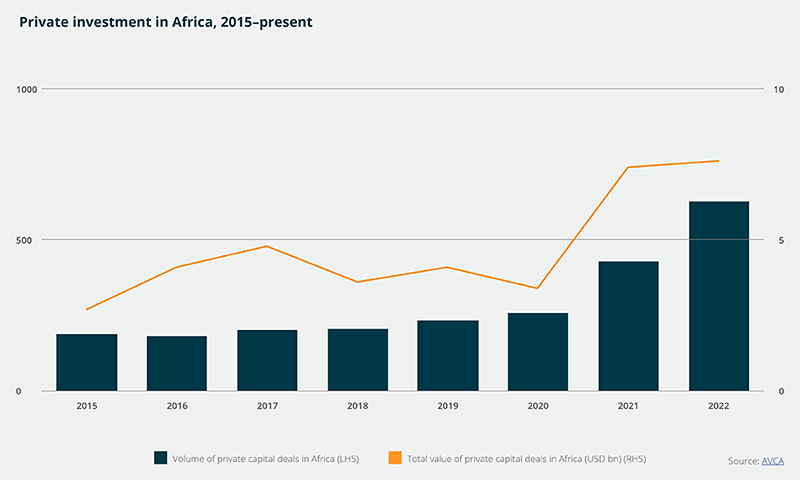

The opportunities in some of Africa’s fast-growing economies such as Ethiopia, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Rwanda, Ghana, Kenya and Mozambique are well known. Africa saw the largest private capital growth of anywhere in the world in 2022. While extractive industries still dominate investment flows in Africa, private capital outlays across sectors including financials, retail, industry, IT, and health are beginning to keep pace.

Investors active in these locations need to go beyond compliance-driven due diligence and develop a nuanced, in-depth and location-specific understanding of terrorism financing risks and typologies. This should stretch from the market entry stage to how these may evolve in the medium-to-long term.

Insecurity at a generational high

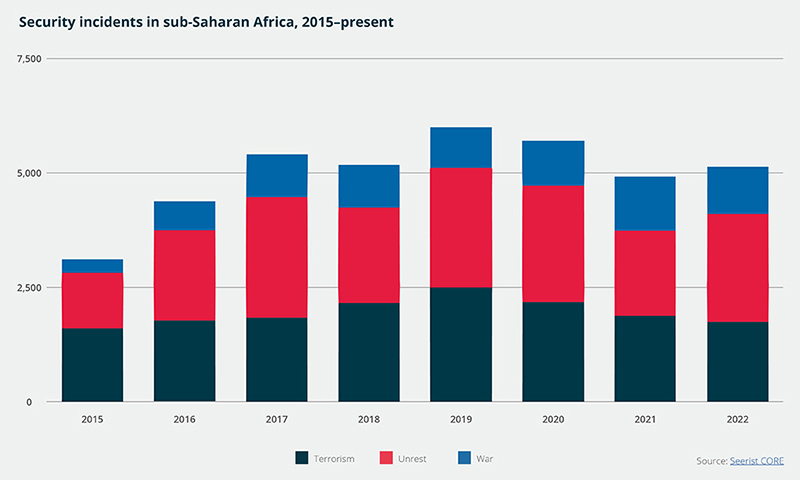

The need to revise due diligence approaches in sub-Saharan Africa is driven by a security and terrorism risk environment that is at its worst since the turn of the century and deteriorating. This is in part guided by external geopolitical factors and shifting relations with the West such as the disruption to US-Africa policy seen under the Donald Trump administration, , which have constrained diplomatic and counterterrorism efforts. But it is also informed by the global economic downturn; democratic backsliding following numerous coups; and increased sophistication and organisation of non-state actors. And this is without considering the ripple effects that the Ukraine war will have on security cooperation.

African theatres of insecurity are also rapidly shifting. This includes the coastward expansion of Islamist militant groups in the Sahel, potential destabilisation in East and Central Africa due to the Sudan conflict, diplomatic flare-ups and violence in Great Lakes Region, an increase in military regimes, and an enduring insurgency in the Cabo Delgado province of Mozambique. As a result, terrorism financing risks are beginning to extend beyond historically high-risk areas.

Where investors are at risk

Investors are exposed to terrorism financing risks both directly and indirectly. The former involves terrorist actors leeching onto a commercial venture, such as through a hidden owner, beneficiary, or affiliation. The indirect risks involve external actors exploiting operators through extortion, theft or security threats such as kidnap-for-ransom.

In some parts of the region, including countries such as Somalia, where government structures are weak or absent, terrorist groups operate in a taxation vacuum. This often occurs through links to political elites in state institutions and makes it difficult to distinguish between official tax channels and extortion by terrorist groups.

A major source of both forms of risk in Africa are natural resource supply chains, such as gold and precious metals, oil and cash crops. Operators face illegal extraction, theft and the obscured involvement of non-state actors around concession areas. The proceeds of terrorism financing activities then filter into all manner of businesses, including the financial system through money laundering and into the hands of end-users further downstream such as industrial, retail and technology companies.

Such permeation of terrorist organisations in legitimate business activities means that even superficially spotless local partners can be affected. This may be caused by vulnerabilities in their organisational structure such as unclear ownership, or structural factors such as poor government oversight in the local area where the company operates. While many companies will claim to have a zero-tolerance policy on terrorism financing, the means put towards upholding this commitment are simply inadequate to effectively analyse and mitigate these risks.

Control Risks has advised clients on a number of cases, from banks exposed to terrorism financing risks due to artisanal gold mining in the Sahel, to evaluating supply chain traceability risks in the tin supply chain in eastern DR Congo, to cocoa and coffee production allegedly linked to the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a militant group with growing links to IS operating in that region. The complexities and nuances in each case illustrate the value of comprehensive due diligence on partners and stakeholder mapping. For longer-term investment, there is equally a need for security risk assessments to understand the potential threat actors and typologies associated with these.

Moving beyond compliance

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) recommendations five, six and eight set the international standards for states establishing measures to prevent and combat terrorism financing. These recommendations laid the foundations for the current requirements for organisations to conduct risk-based due diligence specific to a venture or transaction. From a counter terrorism financing perspective this mainly involves ensuring that these stakeholders are not associated with designated terrorist groups or individuals, and that the venture is compliant with relevant anti-money laundering and counter terrorism financing regulations. However, the complexity and evolving nature of terrorism financing risks in Africa demonstrates the need to go beyond compliance-driven due diligence.

Rather than conducting due diligence solely on direct stakeholders associated with a specific transaction or partnership, organisations should conduct a comprehensive analysis of the associated integrity, security and political risk environments. This should include due diligence of associated stakeholders, a security and political risk assessment from both a local and regional perspective, and a stakeholder mapping exercise to understand the players on the local level that influence how organisations can operate and develop. The need to devise a more holistic approach is also informed by African countries increasingly making efforts to comply with money-laundering standards, although South Africa’s recent greylisting by FATF shows that progress is not a given.

These investigations should go beyond assessing risks associated with designated terrorist groups only and include analyses of violent non-state actors in the region that may sympathise with or have the potential to be affiliated to designated groups in future. In addition to a “point in time” assessment at market entry, these analyses should also be forward looking and forecast the operating environment in the coming three-to-five years. This will enable compliance teams to gather more targeted strategic intelligence, predict how terrorism financing risks may evolve in the years to come, and develop prevention and mitigation measures accordingly.