The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the oil and gas industry in West Africa has so far been uneven. Major producers are bearing the brunt of economic challenges, while newcomers face losing out on future investments as exploration plans are thrown into doubt or delayed indefinitely.

In this article, we examine how Nigeria and Senegal – two countries at very different stages of the oil and gas project cycle – have navigated the pandemic so far and how it will affect the outlook for the industry in both countries.

A tale of two countries

Nigeria’s financial dependence on oil is no secret. The slump in oil prices has hit government finances hard, leading it to rely even further on borrowing to finance its spending. The budget deficit had already reached 4.8% of GDP in 2019, significantly above the 3% stipulated by law. A combination of depressed revenues and increased borrowing looks set to drive a further increase. With resources stretched, raising revenue and limiting spending will remain the government’s primary objectives. These will determine if and how it supports new projects, such as developing new fields, and diversifies the economy away from its dependence on oil.

As an industry newcomer with only two major projects in development, the government in Senegal does not yet collect revenues from oil and gas production, and the pandemic has not resulted in any immediate financial losses. However, delays to scheduled oil revenues have the potential to throw the government’s development and debt strategy off track. According to the IMF, the oil and gas industry will drive a 7% increase in Senegal’s GDP over 20 years. If current projects suffer setbacks, projected revenues to fund the second phase of President Macky Sall’s flagship development plan will be reduced, leaving the government cash-strapped and unable to meet several debt commitments.

Delays ahead

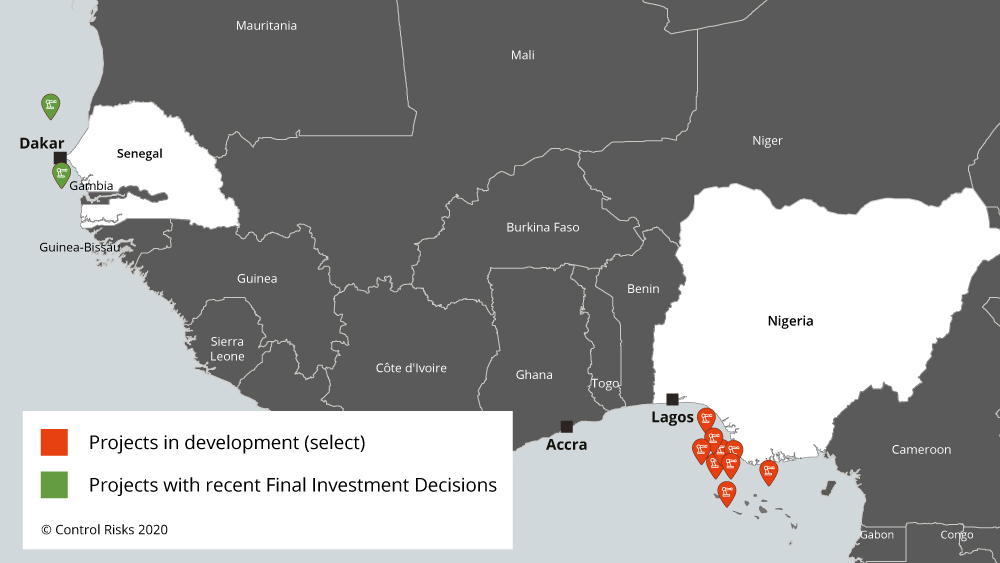

The global economic disruption caused by the pandemic will delay future investments in West Africa. In Nigeria, it will combine with regulatory uncertainty driven by the ongoing failure to progress the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB), a flagship reform bill first introduced to the legislature more than a decade ago, to further discourage new investments. Several international oil companies have delayed final investment decisions (FIDs) in recent years, partly as a result of regulatory uncertainty. Collectively, these projects are valued at USD 58.4bn and predicted to add almost 760,000 barrels per day (bpd) to Nigeria’s production capacity, almost a 35% boost.

With the continued uncertainty over the future of the PIB and global oil markets in turmoil, the government will instead turn to smaller, domestic firms as it seeks to boost production from marginal fields – smaller fields that have not been exploited by oil majors and have remained inactive for more than ten years. More than 600 firms have expressed interest in a marginal field bid round that opened on 1 June, the first in 18 years. However, financial challenges at local operators, opaque government decision-making processes and regulatory changes in recent years that have undermined the financial viability of such operations mean that turning to marginal fields is unlikely to provide the boost to the domestic industry the government is hoping for.

In Senegal, where FIDs have been taken on only two major projects, the government remains keen to consolidate progress and encourage more exploration. The country has been partially sheltered from the standstill in the global oil and gas industry. Despite media reports that development plans will be delayed, Senegal’s first oil project – the Sangomar field -- remains on track for first production in 2023. Operational delays on the project have so far been avoided, with drilling due to start as expected in mid-2021.

However, an initial 31 July deadline for an oil licensing round for ten blocks launched by national oil company PETROSEN in January has been pushed back to the end of September. Meanwhile, the Greater Tortue Ahmeyim project, Senegal’s first liquefied natural gas (LNG) project, missed a key weather window for submarine construction. In April, a month after Senegal’s government declared a state of emergency in response to the pandemic, the oil major on the project declared force majeure. The project is likely to be delayed by at least a year from its 2022 initial deadline.

Nonetheless, although oil majors will be selective with investment decisions, they are likely to seek to expand their portfolios in West Africa if they see opportunities for strategic gains. In Senegal, financial woes among operators have created a last-minute opportunity for investors. In June, after months of speculation, the Australian FAR Ltd, one of the joint-venture partners on the Sangomar oil field, defaulted on payments, opening the door for potential new investment in the project. The Australian company has indicated that it has received a “good level of interest” for the 15% stake in the Sangomar field. It is very likely that either a joint-venture partner or PETROSEN will look to acquire these shares in the coming months.

Two-speed reform progress

With Nigeria’s economy hard hit by the pandemic, the government has sought to further develop domestic industries. On 24 June, it adopted the Nigeria Economic Sustainability Programme (NESP) to stimulate the economy, with a focus on promoting local production. The government has mirrored this approach in the oil and gas sector, with Minister of State for Petroleum Resources Timipre Sylva calling for local content in the industry to reach 70% by 2027. Two bills designed to promote local content – the Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry Content Development Act (Amendment) 2020 and the Nigerian Content Development and Enforcement Bill – in May passed their second readings in the Senate (upper house) and House of Representatives (lower house).

With the Nigerian government increasingly looking to promote domestic sustainability, rhetoric around the importance of developing domestic refining capacity and promoting the involvement of domestic companies in the sector looks set to continue. Nevertheless, the government is unlikely to push so hard on local content as to jeopardise existing investment or efforts to attract foreign investment, which remains its overall priority.

In Senegal, the pandemic has fully absorbed the government’s attention, causing a six-month delay to scheduled oil and gas reforms. Sall had been expected to sign the implementation decree for a local content law in the first quarter of 2020, but the decree is only likely to be published in the coming months. However, a newly announced Economic and Social Resilience Program (PRES) will seek to encourage more public-private partnerships, maintaining the current investor-friendly business environment.

Shifting priorities

As the West African oil and gas industry hits a stumbling block amid the COVID-19 pandemic, energy diversification efforts will also face growing uncertainty. Given revenue constraints in both Senegal and Nigeria, each will focus on developing existing sectors and delay plans to develop alternatives.

The pandemic has highlighted Nigeria’s persistent need to reduce its dependence on oil. The NESP has ambitious infrastructure development targets, and the government hopes that recent reforms in the mining sector will bring in as much as USD 500m annually. Nevertheless, the oil and gas sector is likely to remain the government’s main focus. This is reflected in renewed government efforts to develop the gas sector. Managing Director of Nigeria Liquefied Natural Gas Tony Attah has described Nigeria as a “gas nation that has some oil”. Nigeria has historically not leveraged its gas reserves given an unfavourable fiscal environment and lack of supporting infrastructure, with operators instead preferring to flare gas. Nonetheless, despite increased political will to develop the gas sector, progress is likely to remain slow. Uncertainty around the regulatory framework will continue to deter significant investment in the sector or the infrastructure necessary to develop it.

Significant revenue constraints will continue to undermine prospects for genuine “diversification”. With reforms to this end likely to progress slowly, and the government reluctant to spend significantly, it will remain focused on projects that can create jobs or generate revenues in the form of tax, FDI or foreign exchange.

In Senegal, several dual-fuel power plants will be commissioned in 2022-23 to prepare for first gas production, and existing infrastructure will be converted for this purpose. Around USD 300m will be invested in the construction of three pipeline networks across the country, linking offshore gas to onshore power plants. Nonetheless, the government will remain dependent on international funds for the construction of public energy infrastructure. In 2019, two new solar plant projects (Kael and Kahone) were announced after the International Finance Corporation (IFC) approved a USD 6.9m loan. This was in line with government priorities prior to the pandemic. However, as the government reviews which large capital projects must be delayed or repurposed as it seeks to redirect funding to pandemic response efforts and debt obligations, efforts to diversify power supply may well be put on hold.