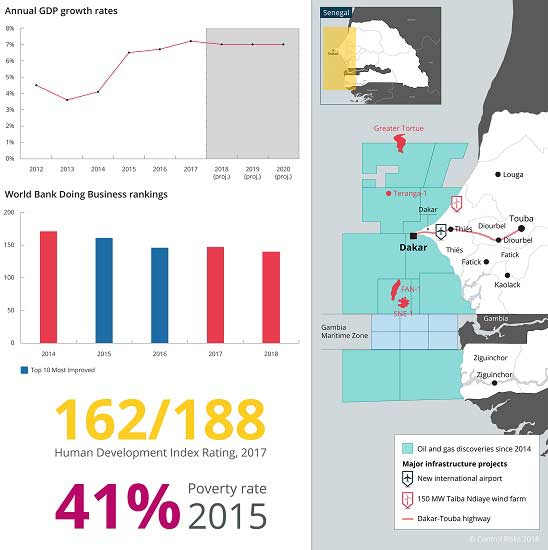

Four years after the first discovery, and Final Investment Decisions (FIDs) are expected in the coming months for the development of the two sizeable deposits: the SNE oil field, operated by Cairn Energy south of Dakar, and the Greater Tortue gas field, a cross-border project developed by a consortium of British Petroleum and Kosmos Energy along the Senegal-Mauritania maritime border. The latter, due to start production in 2022, contains at least 15 Tcf of recoverable gas, making it West Africa’s biggest offshore gas deposit.

Inevitably, the discoveries have encouraged explorers to look further afield for analogous deposits along the West African Atlantic Margin, north and south of Senegal. Two oil majors have already expressed interest in Guinea, while the six blocks making up Gambia’s narrow maritime zone, just south of the SNE discovery, are a hot commodity. Even crisis-prone Guinea-Bissau is attracting some – admittedly more cautious – interest.

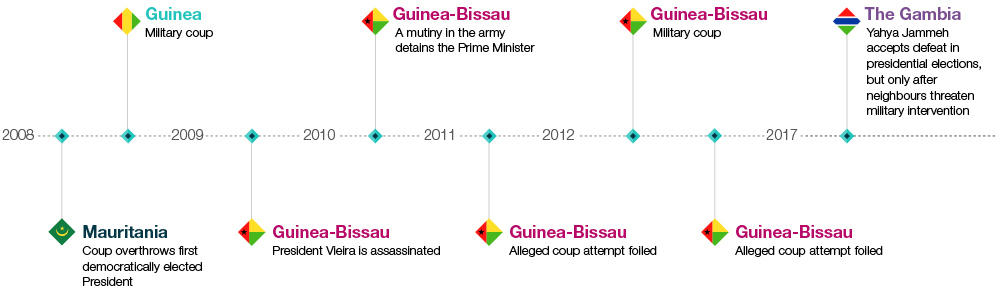

While the geology may look promising, the countries of the so-called Mauritania-Senegal-Guinea-Bissau Basin (MSGB) share two less attractive characteristics: a lack of prior experience with the oil and gas sector, and elevated levels of political volatility, with violent transitions of power having occurred in all bar Senegal in the last decade.

These factors will present several above-ground challenges for the pioneer generation of explorers flocking to the region. Below are seven lessons that investors looking for “new oil” would do well to take into account.

1. Be prepared for drawn-out discussions and possible misunderstandings in light of inexperienced and underdeveloped institutions. The oil and gas sector remains in its infancy in most West African countries: institutions are underdeveloped and focused on downstream distribution, or altogether non-existent. For example, Guinea’s National Petroleum Office (ONAP) has fewer than a dozen staff members working on exploration, most of whom have received only outdated training. Understanding of the complexities of the sector among the top tiers of government is also limited. Senegalese President Macky Sall’s background as a geological engineer and oil specialist has facilitated companies’ interactions with his government, but he will remain an exception among presidents in the region. Technical aspects of offshore oil exploration programmes – and the timeframes and costs involved – are likely to be ignored or poorly understood, increasing the risk of misunderstandings and delays. Companies are likely to have to steer government partners through certain processes.

2. Navigate unclear legislation, but steer clear of bespoke deals. Early investors will also have to contend with incomplete or poorly enforced oil-sector regulations, and inconsistencies between regulations and actual practice. However, regulations are likely to evolve and gradually become more comprehensive after initial finds are made. Senegal, for example, is in the process of updating its 1998 oil code to reflect recent developments. While a degree of pragmatism is required in the meantime to work around incomplete or ambiguous legislation, companies will need to engage with governments in a way that maximises transparency and alignment with current regulations to dispel any perceptions that they have received preferential treatment. Scrutiny of contracts is bound to increase after discoveries, and legacy issues over the negotiation of licences would raise the risk of their terms coming under review at a later date. Several countries in the region, most notably Guinea, are more than familiar with contract reviews in the extractives sector.

3. Know who sits at the other side of the table. Gambian President Adama Barrow is still finding his feet after an unexpected election victory in 2016, and continues to rely on multiple Gambian and foreign advisers for advice. He will be a very different kind of interlocutor to Guinea’s Alpha Condé, who is notorious for his high-handedness in dealing with foreign investors. Guinea’s ONAP director Diakariaou Koulibaly, a vocal supporter of Condé, would be unlikely to survive a change of government; Ousmane Ndiaye, the chair of Senegal’s oil policy body COS-PETROGAZ, has worked with successive presidents irrespective of their affiliation and would be more resilient to a change of government. An understanding of their levels of influence, political affiliations and reputations will be critical to defining an effective long-term government engagement strategy.

4. Watch out for elections, and adjust timelines accordingly. In a system of “winner takes all” politics, presidential elections remain defining moments, suspending or influencing government decision-making on large-scale investment projects. Guinea stands out for its particularly venomous brand of politics, which sees every election trigger accusations of fraud, protests, and mutual recriminations between government and opposition. Elections in Senegal are often more tense than the country’s reputation for stability suggests. The opposition and wider public opinion have increasingly turned on Sall, accusing him of muzzling his opponents, and Dakar – a traditional hotbed of opposition activism – is likely to see localised protests around the February 2019 polls. Meanwhile, Mauritania’s 2019 election could bring a successor to President Mohamed Ould Abdelaziz. In any case, election campaigns will put high-profile oil and gas investments under the spotlight. Governments will pressure operators to achieve certain goals, and make populist promises about the future riches to be derived from oil; opposition candidates will question the way in which licences were obtained. A licence award or an oil discovery during an election season is likely to be exploited by both camps.

5. Mind the expectations gap: it’s not all about governments. Like governments, local media and populations lack experience and understanding of the sector. High-profile investments are certain to trigger a large amount of speculation, misinformed commentary and other forms of “noise”. For example, various media outlets in Senegal have misinterpreted the 10% stake held by the state in oil contracts as an abandoning of national sovereignty in favour of private operators. Companies will need proactive communications towards the wider public to explain their involvement, or they could see their operations shrouded in suspicion from the outset. Managing expectations will also be a major challenge. Production levels at current estimates are unlikely to be an economic game changer, or to provide mass employment or local infrastructure, with operations concentrated offshore. The mismatch between expectations and reality could expose foreign investors to rising hostility in the long term, potentially stoked by populist politicians. Further along the West African coast, the initial excitement generated by oil discoveries in Ghana in 2007 has since given way to local frustration over unmet promises for job creation and economic salvation.

6. Anticipate security challenges. Dakar is an attractive target for Islamist militants operating in the Sahel, while questions remain over whether a rumoured non-aggression pact with Mauritania will protect the country from further attacks in the coming years. On a day-to-day basis, maritime security is likely to present a further headache: piracy levels remain low along the coast, but operators will receive little maritime security support from government navies, while their questionable ethical record could generate reputational risks. Private security providers are generally equally ill-equipped to provide maritime support, or to provide the level of professionalism and integrity required by major multinationals, necessitating careful management.

7. Nurture a local ecosystem, but beware of unsavoury associations. Supporting infrastructure – from port facilities to specialised services – is inadequate in all countries, and will require a significant ramp-up in local capacity. This will present new opportunities for infrastructure contractors and service providers, but also create new challenges related to local content. During a recent visit to Dakar, a foreign diplomat told Control Risks his biggest concern was that “the local private sector has not yet fully realised what it will take in terms of professionalism and resources to satisfy the requirements of these very demanding customers”. Local content is poised to become a government priority in Senegal and Mauritania in the coming years as projects develop, forcing companies to invest time and engage in capacity-building in local private-sector partnerships. However, the boom will also bring its fair share of politically connected entrepreneurs (particularly in Mauritania), whose ability to honour contracts is likely to rest on shaky ground. Any problematic political affiliations should be screened as part of a due diligence exercise into a candidate’s track record.

Author

- Vincent Rouget, Analyst