The East African Community (EAC) will meet in November to discuss membership bids by Somalia and Congo (DRC). We consider the progress made by and challenges facing the regional bloc, and the implications of potential expansion.

- We expect further progress on trade integration between member states in the coming years, driven by domestic economic considerations and infrastructure investments by multilateral institutions.

- Companies will find it increasingly easy to trade within the EAC, given efforts to ease restrictions on the free movement of goods, services and people within it.

- However, tensions between member states’ leaders, similarities in economic structures and competition to attract international investment will continue to limit the benefits and extent of integration.

- Despite the clear market benefits of admitting two new states, the new entrants will exacerbate existing, and likely create additional, fault lines within the EAC.

Trading places

The EAC is frequently ranked as the most advanced of the regional economic communities in Africa, especially since it introduced a common market in 2010. Although intra-regional trade continues to account for a small proportion of the international exports and imports of member states, trade between its member states has steadily increased since the early 2000s. Landlocked Uganda and Rwanda in particular have benefited from improved regional and international market access for their goods and services.

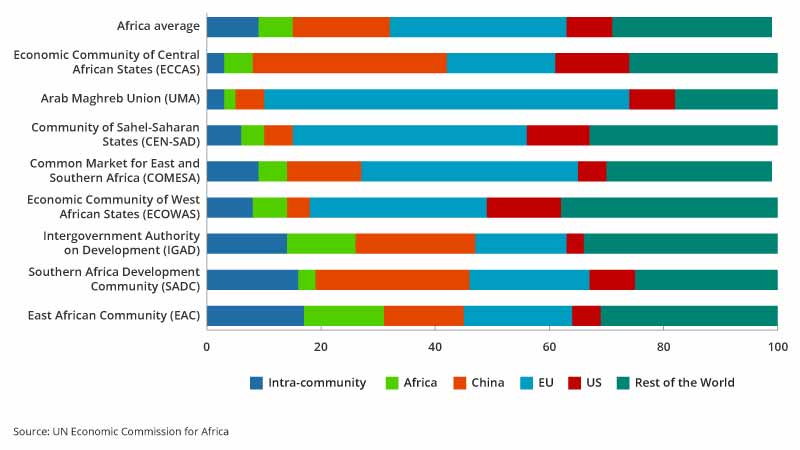

Africa import trade by partner, 2010-17 average

In addition to receiving extensive funding for regional infrastructure projects from international donors, political will among certain member states has driven the EAC’s achievements. A core group comprising Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni and Rwanda’s Paul Kagame has made significant progress towards integrating trade systems and infrastructure. This includes the launch of one-stop border posts, a single customs territory (SCT) and the harmonisation of product standards. The three have also launched a single visa system that is expected to boost tourism arrivals in the coming years.

The benefits for companies resulting from these initiatives will continue to be realised in the coming years. The average cost of moving goods has fallen significantly, as has the time taken to clear goods between borders. For example, the SCT is estimated to have reduced the time taken for customs clearance from an average of 21 days to three-to-five days at selected entry points. More recently, member states have made efforts to integrate their labour markets, allowing the cross-recognition of professional qualifications in each other’s territories, thereby opening a larger labour pool for companies within the EAC.

Community spirit

So far, so good. But the EAC is also rife with feuds, trade disputes and regional rivalries. These will make the pace of regional integration more chaotic and dampen hopes for the emergence of a fully integrated trading area.

First, the factors that bind the region together also fuel competition and impede the development of common policies. With similar economic structures, and agriculture accounting for the majority of exports, there is little complementarity in trade. Goods produced by EAC member states are often in direct competition with one another in both regional and international markets. For example, Kenya and Tanzania are frequently at odds over trade in agricultural commodities, including live animal imports. More recent disputes between the two countries have also involved goods such as confectionery and beverages, as well as a ban on tour companies from each country operating across the joint border at the Maasai Mara/Serengeti game reserve. Such issues will continue to undermine the development of regionally integrated supply chains, crucial to improve the competitiveness of East African-produced goods in international markets.

Second, regional diplomacy is driven by big personalities, who can quickly turn from friendly neighbours to bitter rivals. For example, Rwanda and Uganda have closed their main crossing point since February over accusations that each is bent on spying on or otherwise destabilising the other’s government. Rwanda-Burundi relations have been frozen since 2015 over similar security issues.

With EAC institutions lacking funds and capacity, the bloc has so far proved to be an inefficient mechanism for resolving regional trade disputes and domestic conflicts. The EAC-led political process in Burundi has stalled, while Angola and Congo (DRC), not the EAC, brokered a 21 August “friendship agreement” between the Rwandan and Ugandan presidents to de-escalate tensions.

Political considerations and bad blood between leaders will continue to periodically cause trade disruption, regardless of signed and ratified protocols. They will also cloud prospects for deeper integration over the longer term – for example, towards a common budget or monetary union – which would require countries to abandon key elements of national sovereignty.

Further confusing the picture, EAC member states also belong to other regional economic communities, including the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) and the newly signed Africa Continental Free-Trade Area (AfCFTA). Countries such as Tanzania epitomise this confusion, with one foot in the EAC and the other in the SADC, which Tanzanian President John Magufuli will chair in the year ahead. This multiple membership issue will continue to present challenges for trade compliance, given the variations in product standards and preferential tariffs in place for the different blocs.

New entrants

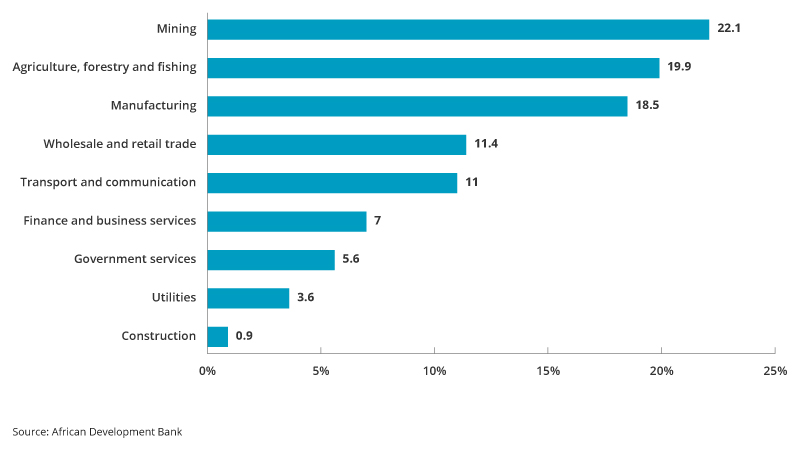

The prospective entry of Congo (DRC) and Somalia in the coming years will further complicate these dynamics. Most member states have welcomed bids by others to join, especially that of Congo, whose extensive natural resources and large, mainly untapped domestic market will be attractive to both EAC-based and international companies. Together with potential offshore gas finds off the Somali coast, this could boost the economic prospects of the entire region. The November summit is likely to see the EAC greenlight the start of formal admission procedures for both countries, paving the way for their entry in the early 2020s.

Congo (DRC) economic structure

However, the entry of Congo in particular would be more likely to encourage competition than coordination between existing members. Kenya would likely seek to lure Congo with its more developed transport system (known as the “northern corridor”) and access to a sophisticated services industry. However, Congo’s proximity to Tanzania’s alternative transport routes (the “central corridor”) would also be an attractive pull factor for it to strengthen integration with Tanzania. Meanwhile, Congo’s entry could see the role of Rwanda and Uganda in the EAC expand further, given their proximity and existing, albeit controversial, ties with trading networks in eastern Congo.

Nonetheless, internal dynamics in Congo and Somalia will be the primary factor shaping their engagement with the EAC. Congo’s complex bureaucracy and inadequate infrastructure will remain significant hurdles to its efforts to build new trading relationships. In Somalia, building a stable political system and government bureaucracy, and combating the al-Shabab insurgency will similarly take precedence over trade agreements with its neighbours. In this context, the region is unlikely to see benefits from an enlarged EAC any time soon.

Part of the Big Picture Series, taken from Seerist.