The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is likely to drive a range of security threats in sub-Saharan Africa in the coming weeks.

- Patience with government curfews and lockdowns is starting to wane. Social unrest will become more likely in June as the economic impact of restrictions is increasingly felt.

- Rising food prices and, in the worst cases, food shortages are also likely to threaten social stability in the coming months, with parts of East Africa and the Sahel most at risk.

- Systematic targeting of foreign nationals perceived as potential virus spreaders has not occurred, but many countries have seen isolated incidents of harassment of Asian and Western nationals.

- Crime rates have dropped amid stringent lockdowns in southern Africa, but economic hardship will drive rising crime levels over the longer term.

Testing trust in governments

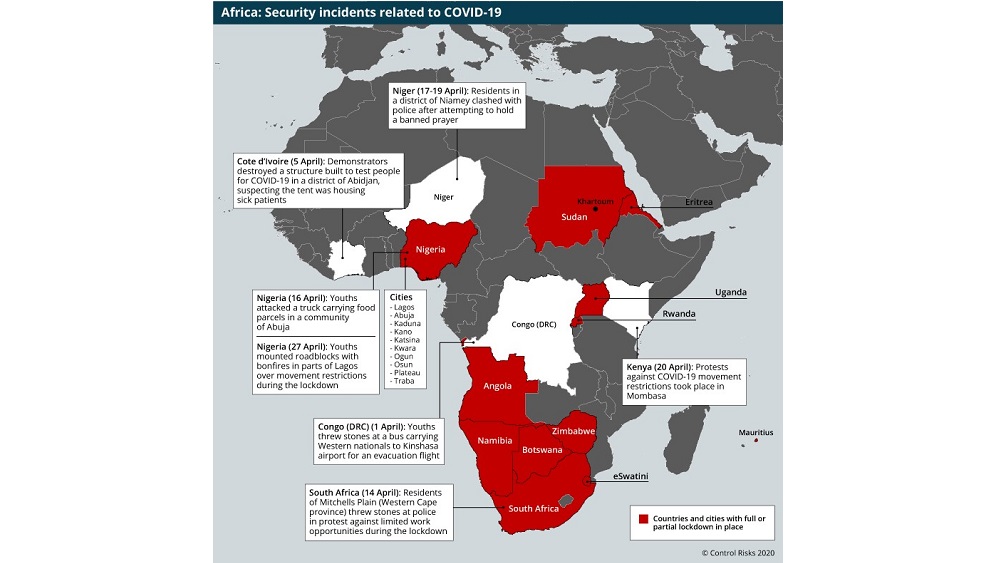

Across Africa, populations broadly cooperated with the stringent restrictions that governments promptly imposed during March and early April to limit the outbreak, including border closures, curfews and lockdowns. However, there are signs that patience is starting to wear thin as COVID-19 tests already low levels of trust in governments, and adds another source of tension to interactions with authorities.

Most countries, with the notable exception of South Africa, have tried to limit the impact of restrictions on those reliant on earning a daily income, recognising the trade-off between protecting public health and social stability. In Nigeria, markets were allowed to remain open with reduced hours during a five-week lockdown in Lagos. In Congo (DRC), the authorities opted to only shut down the wealthiest district of the capital Kinshasa rather than low-income neighbourhoods. Most governments were also quick to relax lockdowns from the end of April, recognising that the policy was economically untenable. Ghana on 20 April was among the first countries to lift a three-week stay-at-home order in Greater Accra and Kumasi amid signs cooperation was beginning to decline. Faced with a growing popular backlash, several majority-Muslim countries such as Niger or Burkina Faso re-opened mosques during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

However, restrictions to travel between the capital and other regions, or night-time curfews persist in many countries, and their enforcement has in many places exacerbated already tense relations between security forces and populations. Incidents of heavy-handed behaviour by security forces have driven criticism in Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa Meanwhile, even countries with historically more positive relations between police and populations, such as Senegal, have seen reports of abuses. Police are reportedly using checkpoints established to enforce movement restrictions as an opportunity to request bribes. Data collected at checkpoints in West African countries showed that illegal taxation had jumped by 50%. Some of our clients classified as essential service providers have experienced harassment despite having the requisite paperwork.

Looming food crisis?

Food shortages and inflation could also threaten social stability in the coming months. The pandemic will exacerbate existing food security issues stemming from locust invasions in East Africa and conflict in the Sahel. The COVID-19 outbreak has so far primarily affected cities rather than agricultural production in farming areas. However, many staples consumed in Africa are imported from abroad, mainly from South-East Asian countries, some of which are restricting exports. Despite substantial increases in domestic production, Nigeria still imports a third of its rice consumption. Senegal’s imports of rice have fallen by 30% in the last month.

This is forcing countries across the region to draw on inventories already at low levels. Border closures, sanitary controls in ports, and travel restrictions to and from capital cities have delayed food imports by several weeks on average, causing bottlenecks in the food supply chain and driving up prices. Border towns and landlocked countries dependent on cross-border trade are most at risk of runaway prices. For example, steep price increases have been reported in the Congolese cities of Goma and Lubumbashi, heavily dependent on trade with Rwanda and Zambia respectively.

The distribution of food parcels in vulnerable neighbourhoods has already triggered tense scrambles in cities from Nigeria to Kenya and South Africa. Governments are stepping in to regulate prices and punish speculation. However, already unpopular administrations, for example in Mali or Burkina Faso, will be watching anxiously, mindful that rises in bread prices triggered the last popular uprising on the continent – in Sudan. Price increases caused by lockdown measures could also challenge the fledgling transitional administration in Khartoum.

A foreign, elite virus

Meanwhile, widespread frustration over the fact that the disease did not originate on the continent, but was imported by a mix of foreign visitors, diaspora returnees or travelling elites, makes the economic costs harder to accept. Asian nationals bore the brunt of such sentiment at the start of the outbreak, and continue to do so in countries where anti-Chinese sentiment runs high. However, with most of Africa’s “patient zeros” having travelled from Europe, resentment has also extended to Western nationals. Isolated cases of harassment and some incidents in which stones have been thrown at vehicles were reported in countries from Ethiopia to Kenya and Côte d’Ivoire. Nonetheless, initial fears of systematic targeting of foreigners by violent mobs have proved unfounded.

Social media will remain a vehicle to transmit conspiracy theories and for those looking to stir xenophobia. For example, a fake video circulated in late April purported to show Chinese shops being burnt in Nigeria in reaction to cases of discrimination against African nationals in China. Such misinformation is quick to cross borders and can inspire copycat incidents in other countries. Closely monitoring viral fake news can help businesses to anticipate and respond to such developments.

Conflict and militancy: essential services

While COVID-19 has taken centre stage, conflicts have continued uninterrupted. The UN’s plea on 10 April to treat war as a “non-essential activity” has fallen on deaf ears across the continent. Islamist militants in the Sahel and Mozambique have both carried out large-scale attacks in recent weeks, likely hoping to capitalise on distracted governments to advance their interests. In Lake Chad, Nigerian Islamist militant group Boko Haram, reeling from a recent Chadian military offensive, has criticised the closure of mosques as it seeks to discredit regional governments and recruit new members. Somalia’s al-Shabab has described the disease as the work of “crusader forces”.

Counterterrorism operations, such as France’s Operation Barkhane in the Sahel, continue, albeit with longer rotations. However, the crisis is having a far more disruptive impact on the work of aid agencies, which are struggling to transport staff and supplies, and is likely to worsen humanitarian conditions in several conflict hotspots. COVID-19 is also likely to see conflict resolution processes and peacekeeping deprioritised amid travel freezes and budget cuts, opening space for militia groups in South Sudan and Central African Republic.

Criminals short of targets

Criminal gangs are also adapting to life under coronavirus. With fewer victims out on the streets, murder rates apparently dropped by more than 70% in South Africa after the start of the lockdown on 26 March, and the outbreak has prompted gangs to call a truce. However, the picture is less positive in Nigerian cities, where the release of prisoners and lockdown hardships have caused petty crime to rise.

Some COVID-19-specific criminal scams have emerged. For example, Kenyan police in early April warned of criminal gangs impersonating COVID-19 surveillance teams on door-to-door testing to conduct robberies. In South Africa, criminals have also posed as workers from the Department of Health to gain access to business and residences.

In the longer term, economic stress will push crime rates upwards. Routine patrols may be deprioritised in favour of enforcing curfews, increasing police response times. Organisations sending staff and executives on short-term trips will also need to plan for longer visits as they navigate travel restrictions, increasing their exposure to criminal activity.

Focus on…

NigeraNigeria reacted swiftly and imposed stringent restrictions, including closing airports and locking down the capital Abuja and commercial capital Lagos. Although these have now been eased, various curfews remain in place including state-wide restrictions. These measures have had significant economic impacts, particularly on daily wage earners, who make up a majority of the population. Government interventions have not been sufficient to mitigate the loss of income, leading to an initial spike in crime and unrest in affected states. As daily life has begun to return to normal, security incidents related to the lockdown including unrest at food distribution centers have reduced.

South AfricaWe expect upward pressure on South Africa’s security environment over the next 12 months, primarily related to the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic and the severity of the nationwide lockdown between 26 May and 1 June, which was one of the strictest globally. These factors have exacerbated existing socioeconomic grievances in the country. The overall security risk is not expected to deteriorate over the next few months, but longer term has the potential to worsen. The nationwide lockdown has severely disrupted economic activity, particularly for small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs), and around one million jobs are projected to be lost over 2020. This will place significant pressure on livelihoods, exacerbating security risks. Moreover, far-reaching economic stoppages placed pressure on low-income groups, given their reliance on the informal sector for work and daily wages to purchase food.

Over the short term, COVID-19 has seen opportunistic crimes in Gauteng and the Western Cape where criminals have posed as workers from the Department of Health to gain access to businesses or residences and subsequently robbed staff/residents. Sporadic incidences of looting have also occurred, though these primarily affect retail outfits, and have become much less frequent since Level 5 of the lockdown was lifted. Outbreaks of localised unrest have occurred since the start of the lockdown, in many cases involving looting of retail stores. Most incidents have taken place in high-density, low-income areas in Gauteng, Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces. We expect such incidents to continue over the coming months as the government maintains restrictions – albeit eased – to flatten the curve as it bolsters healthcare capacity for an eventual spike in cases. However, such protests are likely to remain localised in areas with a low concentration of commercial activity, and are unlikely to spread to business districts. The number and frequency of protests has also decreased as restrictions are eased and police readiness improved. The South African Police Service has responded promptly to contain security incidents, with the assistance of private security services and the South African National Defence Force, the latter deployed until at least 26 June.

Longer term, there is the potential for increased threat of crime, such as armed robbery, carjacking and residential break-ins – the most common types of crime affecting business and personnel. These are persistent issues that typically worsen in tandem with increased socioeconomic pressures. There could be a spike in civil unrest, as trade unions are likely to lead popular protests against layoffs.