Meanwhile, militants in the oil-producing Niger Delta have suspended their attacks on oil and gas infrastructure, with a deal promising them continued amnesty payments and infrastructure development. However, a sustainable solution to the underlying drivers of violence in the region remains out of reach. Militants continue to hold the country’s economic lifeline to ransom, retaining the capability to dramatically disrupt oil output.

Elsewhere, banditry in north-western Zamfara state has become so intense that the president in June this year directed the Nigerian Air Force to conduct aerial bombardments, and in July deployed 1,000 troops to contain criminality. In neighbouring Kaduna state, the Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN), representing Nigeria’s Shia minority, has been campaigning since December 2015 for the release of its leader, Ibrahim el-Zakzaky, who was detained during violence in Zaria in which security forces killed more than 300 Shia Muslims. In the south-east, a separatist movement has increasingly clashed with police and military during its campaign for the establishment of a Republic of Biafra.

Middle Belt crisis politically most damaging for Buhari

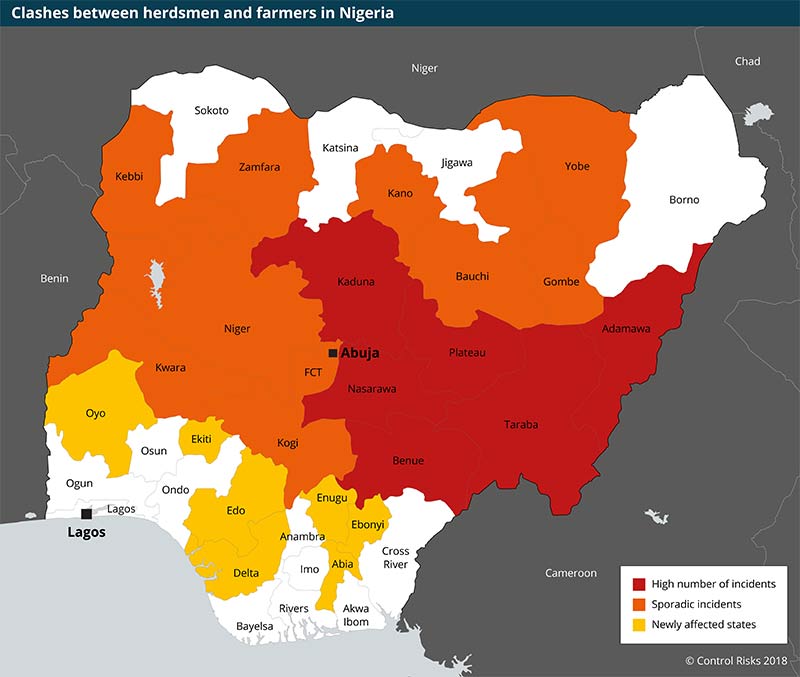

However, as difficult as this continued violence in Nigeria’s ‘traditional’ hotspots is for Buhari, perhaps most politically damaging of all is the recent escalation of clashes between nomadic herders and sedentary farmers in the volatile Middle Belt. More than 1,300 people have been killed since January 2018 – making it Nigeria’s most deadly conflict – and clashes have spread beyond the traditional flashpoints of the Middle Belt.

The conflict, which has rumbled on for decades, has worsened in recent years as changing weather patterns, sprawling desertification and rising population pressures increase competition for land and water. Meanwhile, insecurity in northern states and the Lake Chad region stemming from the Boko Haram insurgency has seen an increase in bandit attacks on herders and their cattle. This has prompted the southward migration of herdsmen outside the typical migration patterns that occur in the dry season.

Although primarily resource-based, the violence also has a strong ethno-religious dimension. Herders are predominantly ethnic-Fulani Muslims from northern states, while farmers are largely indigenous Christians. The Boko Haram insurgency has added fuel to the fire by exacerbating religious sensitivities and increasing local suspicion of Muslim migrants. In Christian communities in central and southern states, nomadic herders are increasingly portrayed as agents of Boko Haram spreading Islam throughout Nigeria – a narrative that is used to justify the rustling or slaughter of Fulani cattle that often escalates into retaliatory attacks.

Security outsourced to vigilante groups

The conflict has evolved from more spontaneous and retaliatory attacks to planned assaults, with both herdsmen and farmers using heavy arms amid a proliferation of illicit weapons ahead of the February 2019 elections. Control Risks’ incident data shows that herder-farmer clashes now routinely involve the use of sophisticated automatic weapons. It also shows an increase in ‘scorched earth’ campaigns, which have seen villages razed to the ground, scores of deaths and mass displacement of civilians in central regions.

Overstretched government security forces are unable to immediately respond to incidents, which primarily occur in remote areas, sometimes resulting in clashes remaining unchecked for several days. This has led to the outsourcing of security to community vigilante groups and ethnic militias.

As a result, vigilante groups have sprung up in communities in the Middle Belt and the south, carrying out attacks on Fulani under the pretext of counterterrorism. This ‘mob justice’ has aggravated inter-communal tensions, encouraging the Fulani to arm themselves and, in some cases, seek protection from militant groups. While militias and vigilante groups are not new to Nigeria, their capability has grown with the increasing availability of illicit weapons. In some cases, militias have even confronted security forces deployed to tackle the violence.

Security will be the key topic ahead of elections

Security in general, and the growing crisis in the Middle Belt in particular, will be a key media topic and opposition campaign theme ahead of the February 2019 elections. Pastoralist communal violence has been heavily politicised to criticise Buhari, who is himself a Fulani Muslim from the north. Inflammatory media reports depict a president who is unduly lenient on his ethnic group, while newspaper cartoons and social media portray Fulani as bogeymen armed with AK47 assault rifles. This narrative is particularly likely to resonate in the Middle Belt with its entrenched ethno-religious divisions.

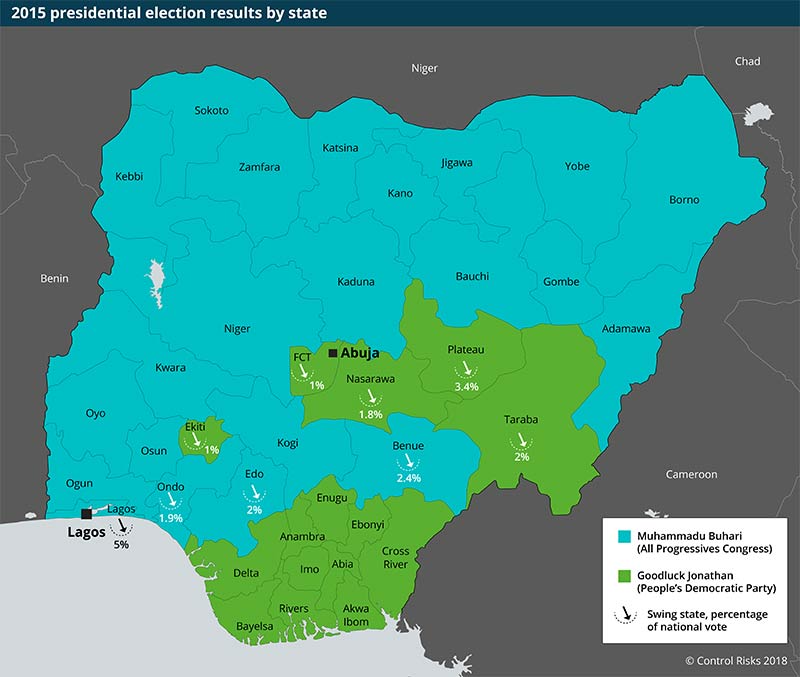

The People’s Democratic Party (PDP), contesting as the opposition for the first time in its history having previously run Nigeria until 2015 since it returned to democratic rule in 1999, will also emphasise the president’s Fulani ethnicity and his failure to contain the spiralling violence. The All Progressives Congress (APC) used a similar tactic in the 2015 general elections, when Buhari focused on then-president Goodluck Jonathan’s (2010-15) alleged mishandling of Boko Haram’s high-profile kidnapping of the Chibok schoolgirls. Buhari accused Jonathan, a Christian from the south, of deliberately ignoring the violence being perpetrated against Muslims in the north.

Defections to the PDP further weaken Buhari’s campaign

The escalation of communal violence is just one of several crises facing the APC. The party has been hit by a series of defections to the PDP in recent weeks. Notable defectors include Senate President Bukola Saraki and Sokoto state Governor Aminu Tambuwal, who have both since expressed their own ambitions to run for president, with Saraki proposing a strong security agenda if he were elected.

Buhari will be particularly troubled by defections in states where insecurity is rising. Benue state Governor Samuel Ortom on 25 July defected to the PDP. In 2015, Benue was one of the tightest victories for the ruling party, and Buhari is likely to lose the state to the opposition next year, largely because of persistent insecurity. An APC defeat in the state will not in itself be fatal to Buhari’s re-election bid, with Benue representing just over 2% of the total number of valid votes in 2015. However, dwindling support for the ruling party in other Middle Belt swing states, such as Plateau and Taraba – both affected by the spike in communal unrest – will make for a nail-biting race.

Author

- Gillian Parker, Analyst