The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has exacerbated the need for Gulf Arab governments to implement localisation policies to reduce their public sector bill and maintain low unemployment rates among their populations.

- The COVID-19 crisis will continue to drive localisation over the coming months by reducing employment opportunities and diminishing government revenue from hydrocarbons.

- Some states will promote nationals’ employment in the private sector while others will primarily seek to earmark public sector jobs for nationals.

- Localisation policies announced during the COVID-19 pandemic will be implemented in a business-friendly manner to avoid hindering a private sector recovery.

- After the end of the COVID-19-induced economic downturn, some states will likely become more aggressive in their private sector localisation policies, such as Saudi Arabia, Oman and Bahrain.

Drivers of localisation

By the late 2000s, all Gulf Arab governments had gradually begun efforts to pare back their provision of public employment opportunities, benefits and subsidies. These governments introduced localisation policies aimed at increasing private sector employment of nationals to reduce government employment costs, unemployment rates and associated social spending.

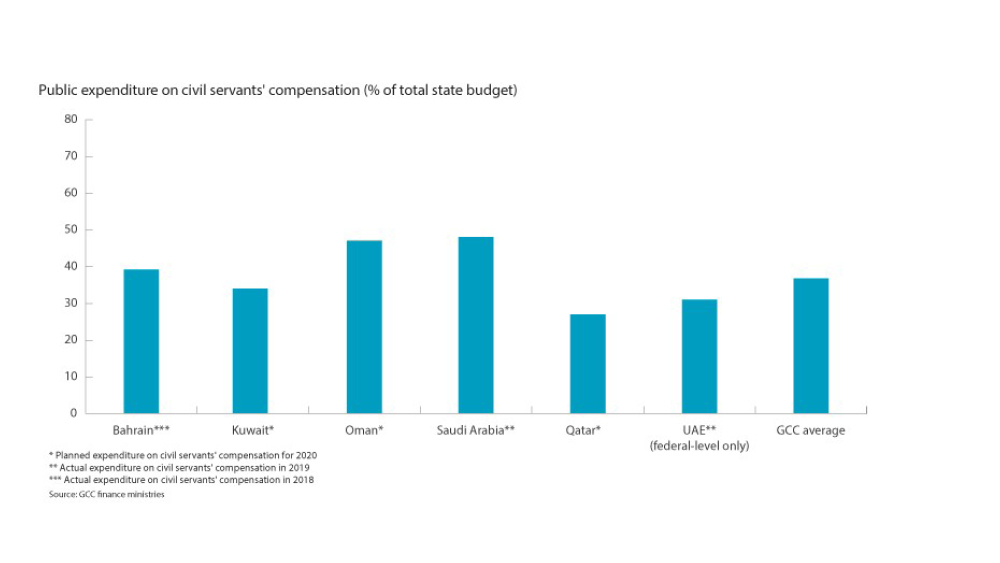

The need for such a shift in the labour market has increased over the past decade following periods of sharp oil price fluctuation, such as the drop in prices in 2014-16. Kuwait in 2015 revised employment quotas: 64% of bank employees had to be nationals. Similarly, Saudi Arabia in 2016 announced a fee for expatriate workers to incentivise private sector companies to hire locally. Riyadh then regularly expanded the list of professions earmarked for nationals and increased employment quotas for nationals. In 2019 it modified the Nitaqat system to further incentivise private sector companies to employ nationals. However, despite these policy changes, Gulf Arab states continue to spend highly on public sector compensation.

COVID-19 shock

The negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on oil prices has revived concerns over government spending. The Brent oil price remains close to 40% below its peak of USD 70 per barrel in January; Control Risks’ strategic partner Oxford Economics forecast that this price will not pass the annual average of USD 50 per barrel before 2022. Natural gas prices also remain low amid reduced industrial consumption worldwide. For Gulf Arab governments that rely heavily on hydrocarbons revenue and usually require oil prices at USD 70-95 per barrel to balance their budgets, the oil market downturn has increased the need to cut costs to mitigate the growing budget imbalance.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact has not been limited to causing a drop in hydrocarbons revenues: it has also negatively affected employment opportunities for populations across the Gulf, particularly among the region’s youth. This has generated conflicting policy imperatives and led governments to differ in their localisation strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: on the one hand, some governments focus on reducing operational costs, while on the other hand, other governments prioritise maintaining high national employment rates.

Government responses

Some Gulf Arab governments have prioritised maintaining or increasing employment of nationals in the private sector. They have expanded the number of professions reserved for nationals, lowered the wage gap between the public and private sector and subsidised nationals’ wages from private sector entities. Some governments requested that private sector companies refrain from laying off locals amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Saudi Arabia in April announced that all ride-hailing jobs would be reserved for nationals and began subsidising 60% of nationals’ wages in the private sector. Riyadh cut the cost of living allowance distributed to public sector employees. Bahrain also started to subsidise the salaries of nationals employed in the private sector in April, and Oman in May announced that it would reduce the salary of new civil servants by up to 22%. In the UAE, the central bank requested that banks retain all national employees.

However, not all Gulf Arab states have been as focused on maintaining or increasing private sector employment to limit operational expenditure; some have instead hired more nationals in the public sector. This usually entails replacing foreign public sector employees with nationals. Therefore, the risk of growing unemployment among nationals is mitigated, but government spending does not reduce and may even increase, as nationals tend to expect high wages.

Kuwait in June announced that it would replace foreign workers in the public sector with nationals and ban all expatriate hires at the state-owned Kuwait Oil Company until the end of 2021. In Qatar, major state-owned entities have cut hundreds of expatriate jobs, and the government has instructed state-owned entities to slash spending on expatriate pay by 30%.

Business impact

Some governments have chosen to prioritise protecting nationals’ employment in the private sector; others have resorted to stepping in as employers amid the economic downturn. Such differing approaches will have varying impact on labour risk. Saudi Arabia, Oman and Bahrain will likely be more aggressive in promoting the employment of nationals in the private sector over the coming months. Oman and Bahrain will continue to face significant budget constraints that the pandemic has exacerbated, and Saudi Arabia will need to generate jobs for its (on average) annual 400,000 labour market entrants.

These three Gulf Arab governments will likely seek to mitigate the costs of new localisation measures on the private sector over the coming months as they seek to preserve their weakened private sectors until they recover from the pandemic-induced economic downturn. For instance, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain have extended partial payments of nationals’ private sector wages and could further lower public sector wages to incentivise private sector employment. However, more assertive measures, such as earmarking certain professions for exclusive national employment and increased national employment quotas, will likely be introduced over the coming years for professions requiring few qualifications, including in the banking, retail and hospitality sectors.

Kuwait has not significantly propped up private sector employment of nationals in recent months. However, it will come under growing fiscal pressure to implement reforms to mitigate the large proportion of the budget allocated to civil servants’ wages to balance government finances amid low oil prices. Kuwait will likely seek to achieve this by increasing employment quotas for nationals across the private sector and dissuading immigration by restricting expatriates’ rights. In the UAE and Qatar, localisation policies will likely be less aggressive, in part due to these governments’ strong fiscal positions and the two Gulf states’ very high dependence on a foreign workforce. However, they are both likely to speed up localisation efforts once they recover significantly from the global economic downturn.