This article is based on content originally published on our partner platform Seerist, a Controls Risks company.

How have the GCC states disbursed different types of financial support and why will they continue to be such large donor countries?

Political stability focuses minds

The disbursement of financial aid – through central bank deposits, loans, investments and to some extent currency swaps – from the Gulf across the region is primarily designed to support governments in times of crisis where their political stability, fiscal stability and legitimacy is under threat.

Ensuring political stability in the MENA-AfPak region in direct response to the political instability which began in Tunisia in December 2010 and spread across the region also became a necessity. Governments in the GCC – namely Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE, with occasional participation from Kuwait – have since become, and will likely remain, the financial backstop of last resort for a number of politically unstable countries.

Ensuring the regional status quo and preserving the stability of pro-Gulf governments across their allies in the region is a fundamental policy priority for the Gulf states. And although Egypt tends to be given a wider berth and is often referred to as ‘too big to fail’, the approach to other countries shows this attitude of influence and preservation is region-wide

Multi-purpose aid

Supporting governments at times of crisis may be the primary purpose of the Gulf states’ largesse, but it is not the sole driver. Providing support that underpins economic stability in a country creates a direct avenue and point of leverage for political influence.

Such leverage is not a given, however. The difficulty in using finance to drive politics can be seen in the changes that have developed over time in the relationship between Egypt and the Gulf states. Between 2014 and 2016, Egypt exhibited independence on two key foreign policy areas.

The first was in 2014 and 2015, when regional support for the Syrian political opposition movement to President Bashar al-Assad was deepening. Egypt refused to side against the status quo, fearing a repeat of its own experience with the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood to political power could manifest in Syria.

The second was when Egypt kept its involvement in the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen to a minimum. Saudi Arabia and the UAE both expended considerable resources in early 2016 on behalf of the Yemeni government to try and reverse the Houthi rebel movement’s takeover of the capital Sanaa.

This strategy of minimal involvement changed when, frustrated by Egypt’s lack of reciprocity after receiving considerable financial aid, the UAE and Saudi Arabia pressured President Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi and the government in 2016 to relent on conditions required by the IMF in talks to approve a USD 12bn Extended Fund Facility (EFF). The Gulf states were influential in ensuring that the large agreement passed inside the IMF. Subsequently, Egypt was the only non-Gulf state to join the boycott against Qatar, which began in June 2017 and continued until January 2021.

New fiscal rules

The dynamic with Egypt also reflected the Gulf states’ changing expectations of how debtor countries should behave. No longer content for debtor countries to use deposited funds as they wished without any meaningful accountability, the GCC states demanded to see more fiscal responsibility, employing a top-down approach to ensure that their support designed to stabilise the economy –, was delivering on this aim and not being taken for granted as an endlessly replenishing handout.

This conditions-based method also underpinned the Gulf bailout to Bahrain in 2018 – USD 10bn from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE – to ensure the government was focusing on building the country’s long-term economic stability through diversification and reducing costs. This bailout followed a USD 10bn package in 2011 from the GCC, which shored up the regime in the face of massive politically and socioeconomically driven protests, but with which the monarchy had done little other than paper over social welfare cracks

The new strictness was driven by a period of instability in the mid-2010s dominated by regional political rivalry combined with the 2015-18 low oil price period. Regional competition was rife, with the anti-Muslim Brotherhood grouping of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt on one side, and pro-Brotherhood Turkey and Qatar on the other. Concerned that more countries could find themselves with governments led or influenced by the Brotherhood, Saudi Arabia and the UAE saw themselves as holding back the tide while carefully balancing the dramatic collapse of their budgets and their own increasing domestic political risks.

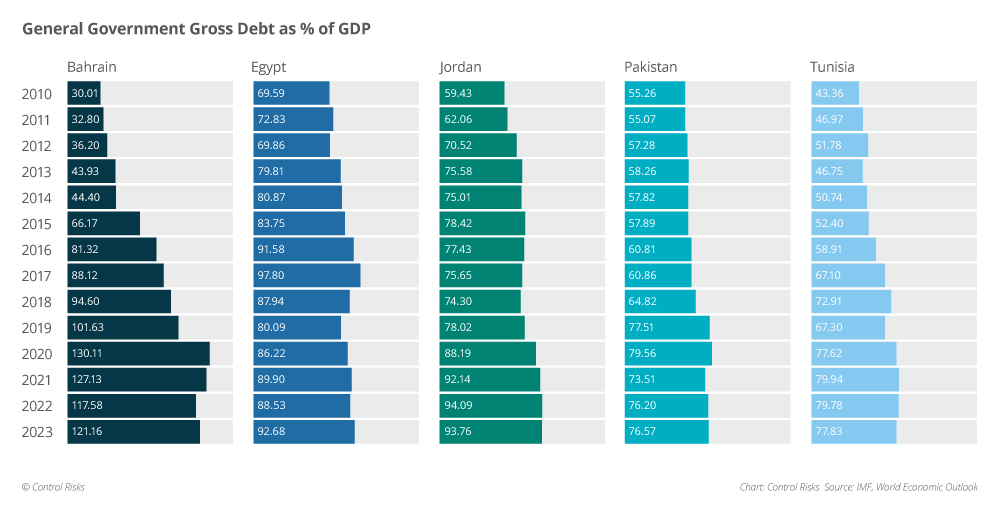

But even with conditionality, government debt in target countries such as Bahrain, Egypt and Jordan has continued to grow. While loans and central bank deposits to stabilise the currency and availability of foreign currency may help governments in some areas, such aid is not the ultimate panacea for balancing a government’s budget.

Future benefits

Since around 2020, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar have all become more proactive in the foreign private sector through buying up government-owned businesses and winning government tenders as bidders to deliver projects. With increasing influence in key sectors of the economy – such as oil and gas, renewables, logistics and transport, real estate development, and infrastructure – this will allow the Gulf states a third lever by which to guide the direction of governments through political, economic and business means.

The sovereign wealth funds of these countries will continue to use this influence as an opportunity to diversify their portfolios. Buying up assets cheaply is always a smart move – and buying up cheap assets in markets that are set to grow through population or gradually expanding economic bases such as Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia, creates the potential for meaningful value growth. Portfolio diversification in these markets is doubly useful, as the markets of nearby neighbours are not considered ‘risky’ or ‘difficult’, whether politically or through regulation, in the same way that markets in Europe or the US might be. Although these are countries that still struggle with economic pressures, their increasing populations and potential for growth are likely to create a backstop for continued value generation, even when the Gulf may be going through periods of saturation or recession.

Soft power with strings attached

The rest of the region can view nationals of Gulf states as high-spending and demanding tourists, and perceives their governments as not respecting debtor governments or people.To help flip this poor perception gain tangential benefit from their economic influence, Gulf states are aiming to cultivate soft power through how they operate in debtor countries, running business effectively, providing stable jobs, and contributing to local communities' security.

While cultivating soft power is not a priority in itself for Gulf countries, the buy-in of local communities can help ensure the success of newly-acquired businesses.