This article is based on content originally published on our partner platform Seerist, a Controls Risks company.

- A fragile coalition cobbled together and led by the PML-N will take office in the next few weeks, navigating multiple challenges and facing a polarised populace while the military maintains substantial involvement in internal politics.

- The government will have to stay the course on the IMF’s ongoing financial assistance programme, but it is likely to backtrack on any long-term programmes over the medium term while structural inefficiencies remain unaddressed.

- With the military at the helm of external affairs and driven by economic troubles, Pakistan will maintain a pivot towards the Gulf countries.

- Initiatives like the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC), created to attract investment from Gulf countries, will remain in place, but the country’s fiscal health will sustain some levels of investor hesitancy.

But first, elections

On 8 February, Pakistan held its long-delayed general and provincial elections in a political environment marked by muted campaigning and amid concerns that the results had already been engineered in favour of the military’s preferred political party, the PML-N. A nationwide suspension of mobile networks in effect on election day coupled with abrupt revisions in result announcement procedures contributed to widespread accusations of poll rigging. Such concerns were further exacerbated as results began to trickle in more than 48 hours after the expected deadline and were not fully announced until nearly four days after the completion of polling.

Preliminary estimates by the civil society group Free And Fair Election Network put voter turnout at 47%, lower than the 51.3% and 53.7% reported in 2018 and 2013, respectively. While political observers expected a far lower turnout, and one that would put the PML-N in a much more comfortable position to form a coalition government, the results have left many surprised.

Former prime minister (2018-22) and now incarcerated leader Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party was widely considered to be the underdog. After being ousted from power in April 2022, Khan has been under arrest since August 2023. A week before the election, a special accountability court convicted him in three separate cases with a combined incarceration term of 31 years and banned him from political participation. Earlier, on 22 December 2023, the Election Commission of Pakistan had withdrawn the PTI’s iconic symbol of a cricket bat – a decision that was contested and subsequently upheld by the Supreme Court on 13 January – forcing candidates from the party to run as independents and creating confusion in a country where illiteracy rates remain high.

Changing of the guard?

Despite these last-minute developments, independent candidates associated with the PTI defied the odds and managed to secure the highest number of seats (93) among the 266 seats that were up for grabs in the lower house. The PML-N followed with 75 seats, while its traditional rival and former coalition partner the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) secured 54.

With no party securing 134 seats out of the 265 elected seats required to form a simple majority in the National Assembly, the country’s key parties have engaged in horse-trading to cobble together a weak coalition. The independents associated with the PTI, despite their victories, have no prospects of forming the government amid the party’s strained ties with the military. Even as the PML-N, PPP, and other smaller parties have united to form a fragile government resembling the former PML-N-led coalition – the Pakistan Democratic Movement (April 2022-August 2023) – they will have to demonstrate prowess in navigating multiple challenges while facing a polarised electorate. This new coalition is expected to take office by early March.

A drastic or significant change in regulatory policies is unlikely during the initial months of the new administration as the new government settles into office. The coalition is marked by varied ideological differences and political interests, so indecisiveness and slow decision-making will likely remain key features. Despite these shortcomings, it is anticipated that the coalition will have, at least at first, the support of the country’s powerful military – the only constant and most influential player in the political arena. Amid another hybrid regime, institutions and regulatory bodies – particularly those associated with key strategic sectors such as telecommunications – will continue to see significant military involvement and oversight while institutional independence continues to take a backseat.

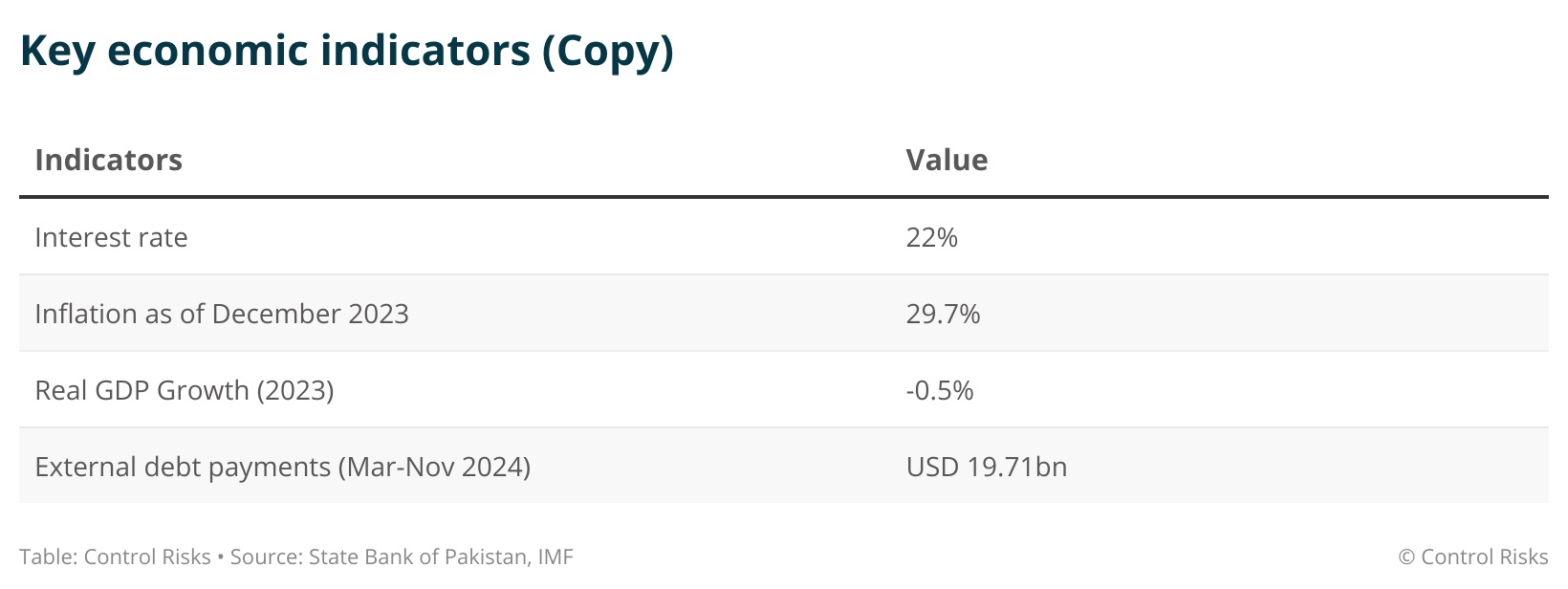

Problems of the purse

According to our strategic partner Oxford Economics, Pakistan’s economy was marked by a significant debt-to-GDP ratio in 2023 – more than 75%. The elected government faces the mammoth task of ensuring recovery following years of fiscal mismanagement by successive governments, including the previous PML-N-led government (April 2022-August 23). Pakistan is currently in the midst of the IMF’s USD 3bn Standby Arrangement (SBA), which is set to expire in April. During its initial months in office, the elected government will stay the course, implementing short-term measures, such as fuel price hikes, to secure the final tranche of assistance.

The completion of the nine-month SBA will do little besides providing immediate and short-term relief to Pakistan’s economic troubles. Sustained fragility will mean that the country will require a much longer-term financial assistance programme, like the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) programme it agreed with the IMF between 2019 and 2023. However, Pakistan has a mixed record in completing IMF programmes, as the recurring derailment of the EFF and similar previous programmes have shown. History is set to repeat itself as the coalition government, led by those who have previously backtracked on commitments to IMF programmes, will likely defer to old practices and succumb to internal pressures by deviating from unpopular but critically-required fiscal policies.

With no strategy to handling the economic and energy crises, or for setting Pakistan on a growth trajectory, the weak coalition government’s ability to address the country’s financial troubles will depend on its ability to implement much-needed structural reforms – progress on which will either remain slow or absent. In line with its predecessors, the elected government will avoid targeting the sectors most associated with the elite interests that form their base vote bank – and that enjoy fiscal incentives and subsidies – while increasing the burden on the national exchequer and sustaining low levels of revenue. The economy will continue to be marked by low levels of foreign reserves and will remain heavily dependent on debt while vicious cycles of current account and fiscal deficits affect its growth potential.

Friends, allies, and foes

With the military at the helm of its external relations, and as it continues to grapple with multiple challenges ranging from a fragile economy to a resurgent militancy, Pakistan will maintain a diversified foreign policy. Islamabad will seek to balance its ties by turning to Washington for support on matters relating to multilateral assistance from the IMF, and by relying on Beijing for shoring up additional foreign direct investment (FDI). Although Pakistan will remain keen to provide fresh impetus to the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), progress on the USD 62bn project will remain slow while concerns over the security of Chinese interests in the country – as well as of Pakistan’s ability to meet its debt obligations – prevail.

Islamabad’s economic troubles will also continue to drive its pivot towards Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, both countries with which the civilian and military leadership share close ties. Even as the elected government takes office, the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) which was created in June 2023 to ensure a conducive environment for investments from these countries, will remain in place. While the instatement of a government with a wider, long-term mandate is likely to translate to foreign assistance and investment from its Gulf allies, continued reluctance stemming from concerns over Pakistan’s fiscal health will mean that any such flows are likely to be limited.

Nonetheless, Pakistan’s economic challenges will be viewed from within a security paradigm. Even its traditional allies will remain wary of tensions in the region. Amid a strained relationship with its long-time rival and eastern neighbour India, and amid increasingly fraying ties with the Afghan Taliban due to a resurgence in militancy, Pakistan will seek to prevent an escalation in recent tensions with Tehran. The new government is likely to focus inwards, driven by its own economic challenges, and will refrain from involvement in wider conflicts in the Middle East.

The new government will face challenges on multiple fronts as its constituent parties remain keen on promoting their individual interests. Doubts over the government’s commitment to economic recovery and prospects of economic growth will weigh heavily on investor sentiments over the medium and long term.

Sources:

“Shehbaz prevails in race for PM House”, Dawn

“Watchdog says voter turnout in Pakistan elections around 47%”, Anadolu Agency