This article is based on content originally published on our partner platform Seerist, a Controls Risks company.

- The authorities will introduce some economic reforms in the coming weeks. They will also maintain flexibility in the foreign exchange regime and delay work on certain state projects.

- However, President Abdul Fatah al-Sisi’s will and capability to significantly drive private sector activity by selling state-owned assets and levelling the playing field between the public and private sector remain in doubt.

- With the regime likely to fail to send a strong signal of its commitment to comprehensive structural reform, it will likely struggle to secure the additional funds it needs to meet its debt obligations.

- As a result, foreign operators will continue to face significant investment risks over the coming months, including contract risks related to delays to state projects.

Root causes

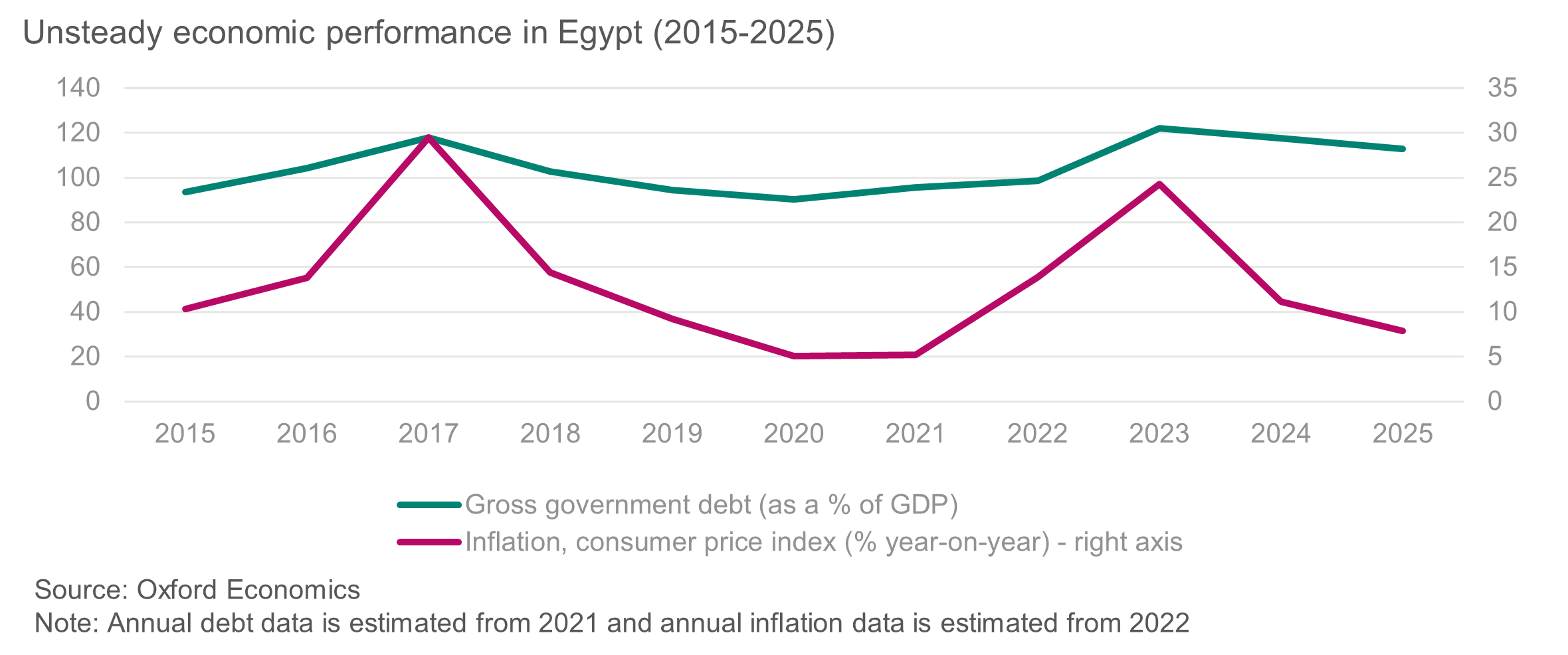

Egypt has experienced fiscal imbalances for several years. Oxford Economics, our strategic partner, assesses that the government’s debt has grown steadily, from 90% of GDP in 2020 to an expected 127% of GDP in 2023. A longstanding trade deficit has compounded the debt crisis and upped pressure on the currency. Amid this current account imbalance, foreign currency reserves dropped from USD 38.6bn in 2018 to USD 26.4bn in 2022.

High government spending in recent years has partly created the conditions for the current crisis. The authorities in November 2022 indicated that they have spent USD 400bn on infrastructure developments (likely since 2014), much of it on prestige projects that have offered limited returns thus far. For example, since 2015 the government has been building a new administrative capital at an estimated cost of USD 60bn.

The spark

Following two years of COVID-19-induced economic difficulties, longstanding structural fiscal weaknesses came to fully bear on the economy when the start of the war in Ukraine in February 2022 sent shockwaves across global energy and food markets. As a major importer of cereals and a net energy importer, Egypt strongly felt the impact of the dual commodity shock. In this context, investors, including many with stakes in Egypt’s debt market, pulled USD 22bn in just six months.

With funds exiting the country, the Egyptian pound (EGP, local currency) came under growing pressure. To mitigate the foreign exchange imbalance, the authorities introduced new rules to slow imports. In particular, the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) in February 2022 issued a circular requiring domestic importers to secure letters of credit from banks to unlock US dollars for cross-border transactions. The measure caused import bottlenecks, resulting in severe pressure on companies’ operations.

Changing tack?

In the face of fiscal pressures, the government in March 2022 turned to the IMF for the fourth time in six years. The negotiations eventually led in December 2022 to an agreement on an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) of USD 3bn to be disbursed in stages over 46 months. The IMF board made clear that the funds were being provided within a “comprehensive” framework of economic reform focusing on “macroeconomic stability, restor[ing] buffers, and pav[ing] the way for inclusive and private-sector-led growth”, including by introducing “wide-ranging structural reforms to reduce the state footprint”.

In line with these objectives, the government has announced it will delay government-led projects that drive foreign currency spending. The central bank has also allowed the currency to devalue further in January, with a US dollar now worth approximately EGP 30. In parallel, the central bank at the end of December 2022 lifted the letters of credit requirement for imports. Through December and January, the government worked to clear the USD 14bn backlog of imported goods held at ports that had resulted from the requirement.

Perhaps most significantly, the government has reaffirmed its commitment to privatisations. Sisi in December 2022 approved a state ownership policy that plans for a decrease in state interests in several sectors, and on 8 February the Prime Minister announced stake sales in 32 state-owned companies by the end of March 2024. On 18 January, the Minister of Planning and Economic Development had announced the country planned to raise USD 2bn-USD 2.5bn in asset sales by mid-2023. In addition, the authorities are reportedly considering levelling the economic playing field, potentially by scrapping or reducing tax exemptions for companies affiliated with the state, including the economically dominant security apparatus.

High stakes

This is not the first time the government has committed to structural reforms of the economy. However, fiscal pressures are currently greater than at any other point in recent years. In addition, the IMF’s proposed disbursement remains a far cry from the total amount that the government needs in external financing – an estimated USD 17bn over the next four years according to the IMF. Sisi will therefore need to demonstrate his commitment to reform if he is to secure additional financial support in the coming months.

Egypt has previously turned to Gulf Arab states for financial support and investments, and will continue to do so; the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia and Qatar deposited USD 13bn in the CBE in 2022. However, after years of support, even these states will be demanding guarantees that their Egyptian investments do not become portfolio deadweights. Consequently, this time around external pressure for structural economic reform is likely to increase and extend beyond that applied by multilateral emergency lending institutions.

Tall order

The government’s renewed commitment to implementing structural economic reform has been positively received by investors globally. The central bank indicated that foreign currency inflows had reached USD 925m in a matter of days following the pound’s devaluation on 11 January.

Still, the necessary economic overhaul will demand significant political will, which will likely remain lacking. Local currency devaluations have driven up inflation and put economic pressure on the population. In response, the government will need to dedicate funds to support the most vulnerable segments of society. For example, on 16 January it said it would start selling bread at a discount to the public. Meanwhile, Sisi’s capacity and will to rein in the sprawling economic interests of the security apparatus remain in doubt. Sisi has been instrumental in strengthening the institution’s grip over the economy in recent years, and the military and intelligence services constitute one of his key power bases.

Consequently, the authorities will likely struggle to send a strong enough signal to the international community as they seek to balance economic priorities with political and social ones. Managing this trade-off will mean that foreign investor sentiment is unlikely to improve sufficiently over the coming months to rapidly and durably reverse the course of the ongoing currency crisis. Credit rating agency Moody’s’ downgrading of Egypt’s sovereign rating further into junk territory on 7 February highlights ongoing concerns.

Foreign companies will therefore remain exposed to significant investment risks. The weak currency will continue to undermine the profitability of Egyptian ventures and drive up the cost of production inputs, while possible further devaluations could see the pound continue to drop over the coming months. In addition, volatile foreign currency supply will likely translate into an illiquid domestic foreign exchange market. Such frictions could translate into renewed import bottlenecks. Finally, delays to state projects will also drive contract and non-payment risks for foreign contractors and suppliers.

Source: Control Risks

This article is based on online analysis provided by Control Risks exclusively to Seerist. Find out more about Seerist – the only augmented analytics solution for risk and intelligence professionals