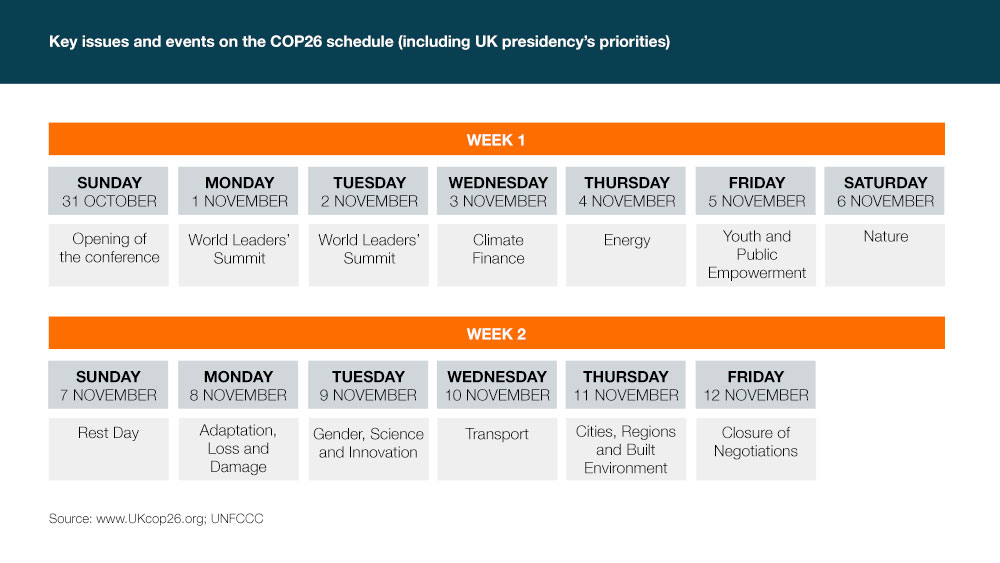

The annual UN climate conference will take place in Glasgow (UK) between 31 October and 12 November. As outlined in our accompanying note, Keeping 1.5 alive – the significance of COP26, the summit’s outcomes will largely be determined by governments’ pledges submitted before the conference. Here we focus on the policy areas that will attract scrutiny in the weeks before – as well as during – the conference.

- Climate finance, coal and adaptation planning will be among the key agenda items at the conference itself.

- The toughest negotiations will focus on carbon markets, where agreement on several key details remains elusive.

- The most significant policy announcements are likely to emerge piecemeal before and during the summit.

- A best-case scenario would see the summit keep alive the 2015 Paris Agreement stretch target of a 1.5-degree rise.

Coal, cars, cash and trees

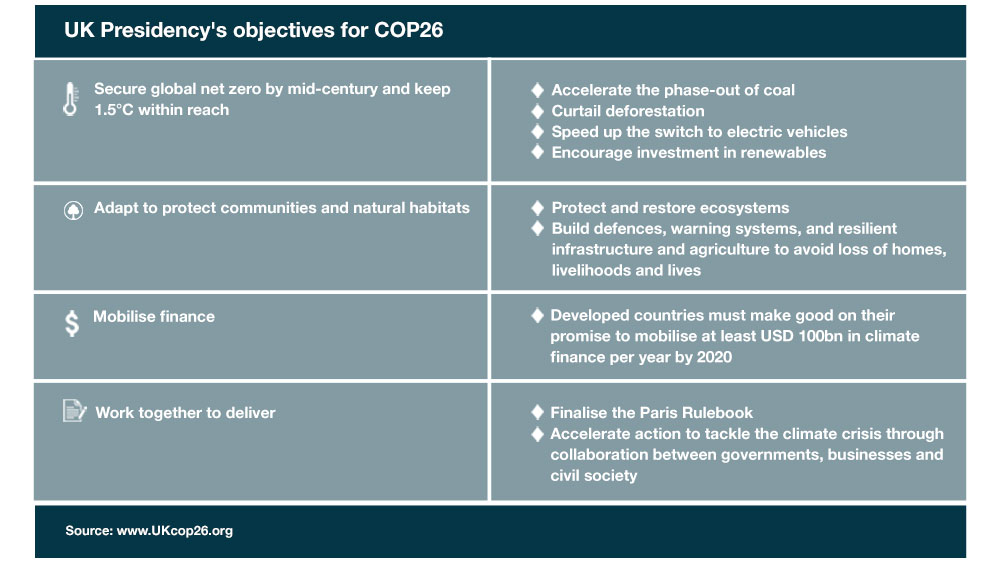

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson has summarised his core objectives for COP26 itself under the tagline “coal, cars, cash and trees”, and has outlined specific commitments on all four that he is seeking from delegations. We believe that the success of the summit will hang on four key areas: climate finance, coal and other phase outs, adaptation planning and finalising the Paris rulebook.

Put your money where your mouth is

Rich countries since 2009 have pledged to mobilise USD 100bn per year to help developing countries mitigate and adapt to climate change. They reaffirmed this in Paris in 2015 and agreed to raise this target by 2025. However, they have consistently fallen short, and it has become an increasing source of rancour at climate negotiations. Many developing countries’ climate pledges are contingent on climate finance (public and private). Failure to secure the sums required would limit their capability to make or to meet ambitious emissions reduction targets.

Wealthy governments including the UK, Germany and Canada as well as the EU have pledged to increase climate finance in recent months. Despite his inclination towards “boosterism” (talking up the UK, making big plans and worrying about the details later), UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson in mid-September only put the chances of hitting the USD 100bn target before Glasgow at just six out of ten.

However, after his commitments to double US funds in April were met with scorn, President Joe Biden on 21 September used his maiden speech to the UN General Assembly (UNGA) to commit to quadrupling the figure to USD 11.4bn per year by 2024. Although the sums required for developing nations to mitigate and adapt to climate change will continue to rise, this will be well received. It is likely that the USD 100bn target will be reached for the first time in 2022.

However, additional commitments are likely to be necessary in Glasgow to generate the necessary good will, particularly among the least developed states that have to date received far less climate finance than other developing economies.

Coal and co.

The UK hosts hope that COP26 will be when the world “consigns coal to history”. A series of major announcements on coal have already been made before the summit begins. In the most notable – and following hot on the heels of Biden’s pledge – China’s President Xi Jinping on 22 September told the UNGA that China (the most significant international financier of coal) will end construction of coal power projects overseas. This followed similar announcements from South Korea and Japan (the second and third most significant international financiers of coal) in April and July, respectively. Together, these will accelerate the collapse in the coal pipeline in emerging markets and will lead to further project cancellations.

With the pipeline dwindling, there will be growing pressure on and impetus for governments to commit to phase-out dates for existing coal projects. A central request of the UK government is that developed and developing nations commit at COP26 to phasing out coal power generation by 2030 and 2040, respectively. Most European governments (as members of the Powering Past Coal Alliance, PPCA) have already committed to the earlier date. If there is to be a major multilateral move on phasing out existing coal projects in the coming weeks – including with support from China – it will likely require agreement at the G20 leaders’ summit on 30 to 31 October. When environment and climate ministers from the group met in July, they failed to reach an agreement on such a phase out, though the most difficult decisions are likely to have been left to the leaders’ summit. If the club’s leaders reach an agreement, it could pave the way for more pledges in Glasgow. However, recent power shortages in China will undermine imminent action on phasing out coal. Until early 2022, the single largest consumer of coal power may boost coal mining and power to ensure residential electricity supplies.

While coal is the main phase-out focus, other initiatives and alliances seeking to set timelines for the end of carbon-intensive activities will attract new members at COP26:

- Costa Rica and Denmark will launch the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA), with members establishing a deadline to end oil and gas production. Few major economies have made significant commitments to phase out production, and it is currently unclear which ones may seek membership.

- The US and the EU will launch a Global Methane Pledge, a global initiative to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030. Although the pact will not set sector-specific targets, supportive governments will likely target quick wins by placing stricter regulations on fugitive emissions from natural gas. Several are reportedly interested in joining.

- Among his central goals for COP26, Prime Minister Johnson has also called on governments to commit to an end to the sale of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles by 2040. In its Net Zero Roadmap published in May, the International Energy Agency (IEA) called for an earlier deadline of 2035. A growing number of countries have committed to ICE phase outs in the last 18 months. With manufacturers responding to these market signals with commitments to end the sale of such vehicles, new government pledges are likely in Glasgow.

While we expect governments to lay out plans to phase out old polluting technologies, it is also likely that leaders will use the coming weeks and the Glasgow summit to outline plans for the expansion of new cleaner technologies. As well as making a commitment on coal when he spoke to the UNGA, Xi stated that “China will step up support for other developing countries in developing green and low-carbon energy”. Expect more announcements on the expansion of zero emissions vehicles and renewable energy capacity.

Adapting to the inevitable

With a temperature increase of 1.5 degrees now all but baked in, and extreme weather events increasing in frequency and intensity, adapting to climate change is just as critical as mitigating it. However, adaptation projects are typically considered a much less attractive destination for private finance than those focusing on mitigation.

The Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) – a club of 48 nations spread across Africa, the Middle East, Asia Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean – on 7 September published its COP26 manifesto, with adaptation at its centre. Recent extreme weather events in Europe, North America and China are increasing the focus on adaptation in these regions too. The issue will attract much more attention than at previous COPs.

Rules of the game

The Paris Agreement does not provide clear instructions on how country pledges will collectively be used to achieve its core goals – for this an accompanying rulebook was necessary. Most of the rules were finalised at COP24 in Katowice (Poland) in 2018. However, reaching agreement on Article 6 proved too difficult in Katowice or at COP25 in Madrid (Spain) a year later. There was also no significant progress on the issue at pre-COP intersessional talks between May and June this year and reaching an agreement will be central to success in Glasgow.

Article 6 outlines voluntary mechanisms to promote investment and ambition through two market-based measures and one non-market measure:

- Article 6.2 would create bilateral cooperation on NDCs by allowing countries that have overachieved (for example on emissions cuts, renewable energy growth or forest expansion) to sell their overachievements (“international traded mitigation outcomes”) to countries that have failed to meet their own pledges.

- Article 6.4 would create a global carbon market to allow for public and private sector actors to trade internationally in carbon credits. Credits would be generated by emissions reductions and would count towards Paris Agreement pledges and would be governed by a UN supervisory body.

- Article 6.8 would create a formal framework for non-market cooperation between countries, for example through development aid.

Article 6 recognises that countries have different capacity to reduce emissions and so achieving deep decarbonisation requires a system that promotes cooperation. Article 6.4 would also provide a means to incorporate corporate climate commitments into what is otherwise primarily an inter-governmental process. Well-defined rules governing Article 6 could help governments (and companies) raise the ambition of their climate pledges by increasing efficiency in their implementation. Increased efficiency would lead to cost savings that could in turn (hypothetically) be reinvested in climate objectives.

However, poorly defined rules with significant loopholes could actively undermine climate objectives. Proposals aimed at preventing double-counting of carbon credits remain contentious and achieving multilateral agreement on the issue in Glasgow hangs in the balance. Brazil in particular may continue to argue for loopholes that others will not accept – double counting could see emissions cuts counted against national targets by both the party selling credits and the party buying them.

Sweat the small stuff

There are certain to be major announcements, but they are more likely to be a drip-feed of new commitments and pledges that fall short of the historic finale achieved in Paris. A best-case scenario sees the curtain close in Glasgow with hope that the stretch target of the Paris Agreement is kept alive. This will not be guaranteed.