This article was originally published in Americas Quarterly.

Policies to fight graft are a low priority in both Brazil and Mexico and have lost momentum in the region as a whole.

Despite a wave of headline-making corruption cases, the hard truth is that most Latin American governments have relegated anti-graft measures to a lower priority in recent years, while voters have been less active and mobilised around the issue. With a few exceptions—as in Guatemala last August—anti-corruption pledges no longer define Latin American elections.

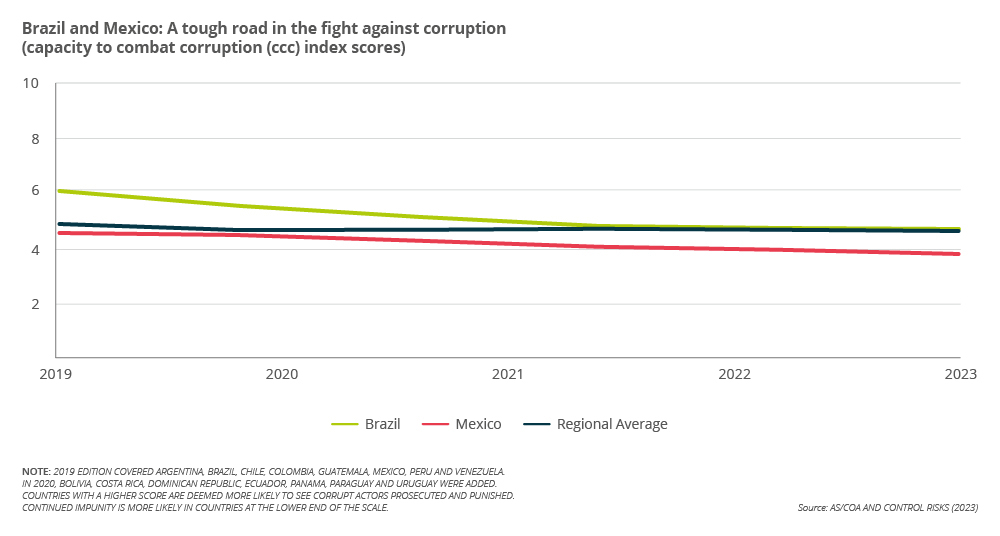

This is especially true in the region’s two most populous countries, Brazil and Mexico, which last decade showed glimpses of hope through high-profile corruption investigations such as Operation Car Wash. Yet, more recently, they have struggled with entrenched corruption and limited political will to tackle related issues. Over the past five years, both countries have faced a particularly troublesome road in the fight against corruption as measured by the Capacity to Combat Corruption (CCC) Index, co-published by Control Risks and the Americas Society/Council of the Americas (which publishes AQ). The index evaluates and ranks 15 Latin American countries based on their ability to detect, punish and prevent corruption.

In the 2023 CCC Index, Brazil’s score stabilised just above the regional average, while Mexico’s fell for the fourth consecutive year. (The next edition of the CCC Index is set to be published in 2025.) In both countries, rhetoric against corruption has proven stronger than their capacity to combat it.

Since the CCC Index was launched in 2019, the region’s trajectory in the anti-corruption environment has been under strain. Attention has shifted to other issues, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent economic recovery, rising crime and, in some cases, democratic backsliding. Recent corruption events highlight troubling trends, from accusations that high-profile investigations are politically motivated to key appointments that risk derailing anti-corruption efforts.

At the same time, collaboration between the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and its enforcement counterparts in Latin America remains strong. Examples include the DOJ’s Anticorruption Task Force aimed at combating corruption in Central America, launched in 2021, and partnerships between the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Brazil, Colombia and Ecuador. Even though these efforts demonstrate some level of interest in prosecuting white-collar crime, they are insufficient to reverse the stagnation trend in the region’s fight against corruption.

Brazil stumbles

The anti-corruption agenda in Brazil gained traction in 2014 after a multi-billion-dollar corruption scandal came to light, leading to Operation Car Wash (Lava Jato). In 2015, Brazilian pollster Datafolha showed that for the first time, voters said corruption was the country’s biggest problem. By contrast, more recent polls indicate that the economy and violence are the two main concerns for Brazilians, with corruption now ranking fifth.

Former President Jair Bolsonaro (2019-22) was elected on an anti-corruption platform, which was still the top concern for voters at that time. However, the Lava Jato investigation was dismantled under his administration. Bolsonaro’s attempts to shield his sons and inner circle from corruption investigations by meddling in the federal police were also a significant blow to the country’s efforts to prevent and combat corruption. (Bolsonaro denied any undue interference with the probe.)

Bolsonaro still faces dozens of probes, including for an alleged conspiracy to incite an uprising after he lost the 2022 presidential election. The electoral court in June 2023 banned him from running for office until 2030 due to the use of the state television channel and official meetings with diplomats to promote his reelection bid and sow distrust about the vote.

While the Supreme Court declared the opaque practice of the “secret budget” unconstitutional in 2022, negotiations between the executive and legislative branches are still heavily conditioned on pork-barrel practices. The distribution and the use of federal funds from lawmakers happen with little oversight or transparency, creating fertile ground for corruption.

Even so, the 2023 CCC Index registered improvements in Brazil’s democracy and political institutions score, reflecting their resilience despite several years of acute strain, and particularly the effective institutional response to the riots of January 8, 2023. However, the current administration is not prioritising an anti-corruption agenda. Instead, it is focused on economic and environmental issues, and President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has openly criticised Operation Car Wash. He proposed to amend the State-Owned Companies Law to allow political appointments to senior positions in state-owned companies, setting off alarm bells over the risk that those entities may be run for short-term political gain over long-term sustainability. This March, the Supreme Court upheld the restrictions on appointing politicians to these companies, but ruled that appointments made since the suspension of the law in March 2023 remain valid.

Mexico’s downward trajectory

In 2023, Mexico lagged behind the regional average in the index’s legal capacity category. This reflected the stagnation of anti-corruption efforts under President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), despite his election on an anti-graft platform. Through AMLO’s Fourth Transformation agenda, his administration has attempted to weaken or dismantle institutions that serve as checks and balances on government power, as well as watchdog agencies tasked with calling out corrupt practices.

Prominent corruption cases remain unresolved; the federal government has frequently attacked civil society organizations and journalists; and the Attorney General’s Office has taken politically motivated actions, particularly at the state level, where governors are often accused of interfering in corruption investigations, deciding who is investigated and the speed with which investigations advance.

As AMLO’s term has approached its end, these issues have become only more pronounced, raising concerns about Mexico’s anti-corruption future. If approved, AMLO’s proposed judicial reform will allow the selection of judges through popular vote. The ruling Morena party’s popularity is likely to spill over to any of its potential candidates for the judiciary, allowing the party to extend its reach across all three branches of government and potentially shield itself from corruption probes.

President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum, who takes office on October 1, will inherit a system deeply rooted in entrenched corruption, which has been exacerbated by political interference and budget cuts for anti-corruption agencies. Despite this panorama, it appears that, for now, she will continue to follow AMLO’s approach on this front.

The road ahead

Sheinbaum will undoubtedly face significant challenges on the anti-corruption front. She plans to create a Federal Anti-Corruption Agency, which will depend on the executive. This dependence will likely undermine its effectiveness in combating corruption. This is not to say moderate improvements will be impossible during her sexenio, but at least in her first year, tangible results are doubtful. In Brazil, meanwhile, the prevalence of opaque mechanisms for the distribution of funds and political appointments in exchange for support in Congress will continue to dent the integrity environment.

However, on the bright side, the continued strengthening of Brazil’s Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Federal Police, which have played a fundamental role in investigating recent corruption cases and punishing corrupt actors, may yield improvements in the years ahead. The Federal Police has spearheaded most investigations involving Bolsonaro, and the Prosecutor’s Office is leading several corruption investigations involving mayors in Brazil.

While a dramatic deterioration in Mexico’s and Brazil’s capacity to combat corruption is unlikely over the coming year, significant improvements seem far off. Anti-corruption measures will remain on the back burner as governments prioritise other issues.

This stagnation in anti-corruption efforts has led to the progressive weakening of the corporate compliance culture in Latin America’s largest economies. This exposes companies to increased integrity risks, though corruption will not be an insurmountable obstacle to business operations and future investment in these countries. For the private sector, Mexico’s security situation and Brazil’s tax burden will remain the top challenges.