This article is based on content originally published on our partner platform Seerist, the augmented analytics solution for threat and risk intelligence professionals.

Costa Rica's security situation is rapidly deteriorating, with skyrocketing homicide rates transforming what was once one of the safest Latin American countries into a much more dangerous environment. The implications for the business landscape are significant. Crime and violence are expected to continue escalating in the coming years, outpacing the government's resources and capacity to tackle the issue effectively.

Without a clear security strategy, the government of President Rodrigo Chaves will struggle to improve conditions amid pressure from the population and business sector. While direct risks to businesses remain unlikely, exposure to incidental violence will become more prevalent, contingent on the local context and the implementation of risk management strategies.

At the front seat

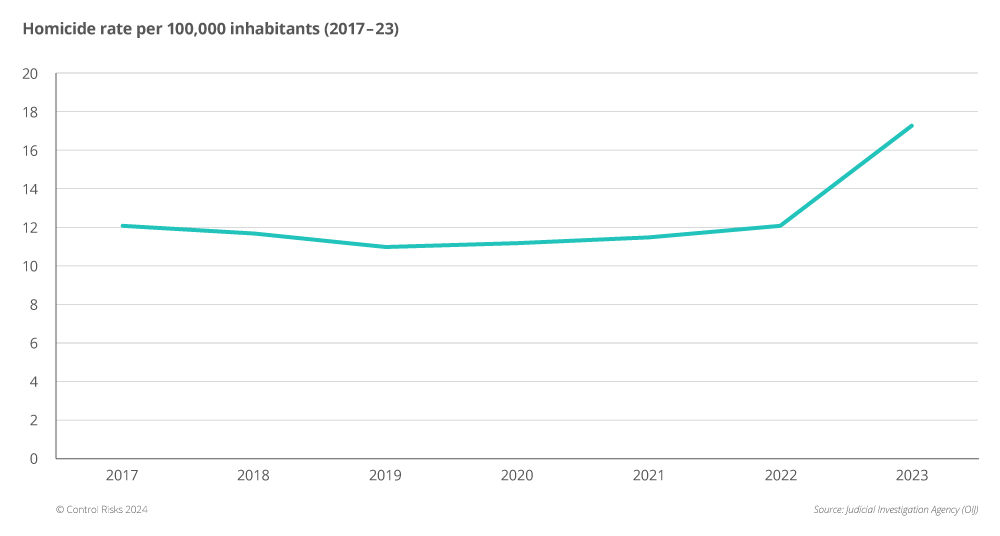

The increasing links between local gangs and transnational groups – mainly from Mexico, Colombia and Venezuela – have made the country a key hub in the international drug trade. For many years, Costa Rica was only a transit point through which small shipments of illicit narcotics were trafficked. Now, local groups have expanded their activities beyond the national level to control international trafficking routes and double their profits. Clashes between local gangs led to a homicide rate of 17.2 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2023, a 38% increase from 2022.

In October 2023, Security Minister Mario Zamora stated that the number of criminal organisations in Costa Rica has increased from 35 to 340 over the past decade. This escalation has led to disputes spilling over from marginal areas and coastal provinces, such as Limón and Puntarenas, into more urban regions. Criminal groups have expanded their territorial presence to include, for instance, the capital San José and the industrial hub of Alajuela province in their efforts to control the drug trade nationwide.

Episodes of violence are also the result of confrontations between law enforcement agencies and criminals. As of 9 July, the Judicial Investigation Agency (OIJ) reports 449 homicides, with Puntarenas and Cartago provinces registering an increase of 16% and 20%, respectively, compared to the same period of 2023. In line with this, perceptions of insecurity among the population are increasing significantly. According to an opinion survey by the Center for Research and Political Studies (CIEP) published in April 2024, 41.8% of Costa Ricans consider insecurity and crime as the most serious problems in the country, compared to 13.3% in October 2022.

No clear road

The increasing activity of transnational criminal organisations will continue to pose challenges to the Chaves administration (in office until May 2026). This will be partially due to the lack of a comprehensive security strategy, the widespread availability of firearms and the limited human and financial resources to tackle violence. Although insecurity is not a new problem, it has significantly worsened since 2022 and the country has not been institutionally prepared to respond. Zamora on 2 May admitted that criminal groups, particularly those associated with transnational organisations, “generate a force that exceeds the current police capabilities, the administration of justice and laws”.

In an attempt to ease the population’s concerns and improve security conditions, the government on 22 February published in the Official Gazette the Costa Rica Segura Plus 2023-30 security plan. Among other things, the strategy includes hiring 1,004 new police officers and another 1,000 by the end of 2024, installing scanners at the Moín port terminal (the country’s largest port) and increasing the salaries of police forces. Concerns around the latter have also created an environment conducive to police corruption and facilitation of criminal activity.

Now halfway through his term, Chaves is rushing to drive improvements in the security environment. Aside from the security plan, he has sought international co-operation to bolster the country’s capabilities and opted for a collaborative approach instead of iron-fist policies (as seen in other countries like El Salvador). Considering the security situation and the government’s capacity, tangible improvements are unlikely at least in the next 12 months.

Business as usual?

Despite the country’s favourable business environment with market friendly policies and increasing investment flows, insecurity will likely become a key challenge for businesses in the coming years. Risks will evolve and vary depending on the location of operations, as well as companies’ security risk management frameworks. Below are some security challenges that key industries will likely face in the coming years.

Although criminal groups do not directly target business operations, organised crime will continue to drive violent crime such as homicides and shootouts. According to OIJ data, 45 homicides were bystander incidents in 2023. This trend has been on the rise since 2021, when only seven such cases were recorded. Areas more prone to this risk include port provinces such as Limón and Puntarenas.

In other areas of the country – like free trade zones and industrial hubs – risks are lower, primarily because such buildings typically maintain robust security measures and protocols, like surveillance. Nevertheless, there are outstanding risks to consider:

- For supply chains: Export-oriented operations will remain prone to criminal infiltration to facilitate the smuggling of narcotics at the country’s ports.

- For personnel: Issues such as inadvertent exposure to violent events, including shootouts or carjacking, and being a target of petty crime will pose the main challenges.