The annual UN climate conference will take place in Glasgow (UK) between 31 October and 12 November. In Keeping 1.5 alive – four issues to watch at COP26, we focus on the policy areas that will attract scrutiny in the weeks before – as well as during – the conference. Here we examine the geopolitical context of the most significant climate summit since 2015.

- National climate pledges will lay the framework for global climate policy for the next decade.

- Revised climate pledges submitted to date are not sufficient to keep global warming within the limits established by the 2015 Paris Agreement.

- The geopolitical landscape heading to Glasgow is also much less conducive to cooperation on climate between major emitters than it was in 2015.

- However, the urgency around action on climate change will likely secure some breakthroughs in Glasgow.

A crucial summit to kick off a crucial decade

Thousands of delegates including diplomats and industry representatives – as well as activists – will travel to Glasgow for the 26th conference of the parties (COP26) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Although COPs are an annual feature of the diplomatic calendar, COP26 is considered the most important climate conference since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015 at COP21. It will also have been almost 23 months since COP25 ended in Madrid (Spain), with COP26 postponed by a year because of COVID-19.

(Photo credit: Miguel Medina/AFP via Getty Images)

In the French capital in 2015, the international community committed to limiting global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial average temperatures, while striving for a more ambitious target of a rise of no more than 1.5 degrees. There is no single mechanism that forces countries to meet specific climate targets. Instead, emissions reductions are based on voluntary (non-binding) Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The Agreement is designed to encourage signatories to increase the ambition of their NDCs every five years by what is called the “ratchet mechanism”. As most parties submitted their first round of climate pledges before or after the Paris summit, their new or revised NDCs fell due by COP26. Like the summit, the deadline was pushed back from the end of 2020 to the end of July 2021 to account for the disruption caused by COVID-19. Although it is not mandatory to implement NDCs, preparing and communicating them is.

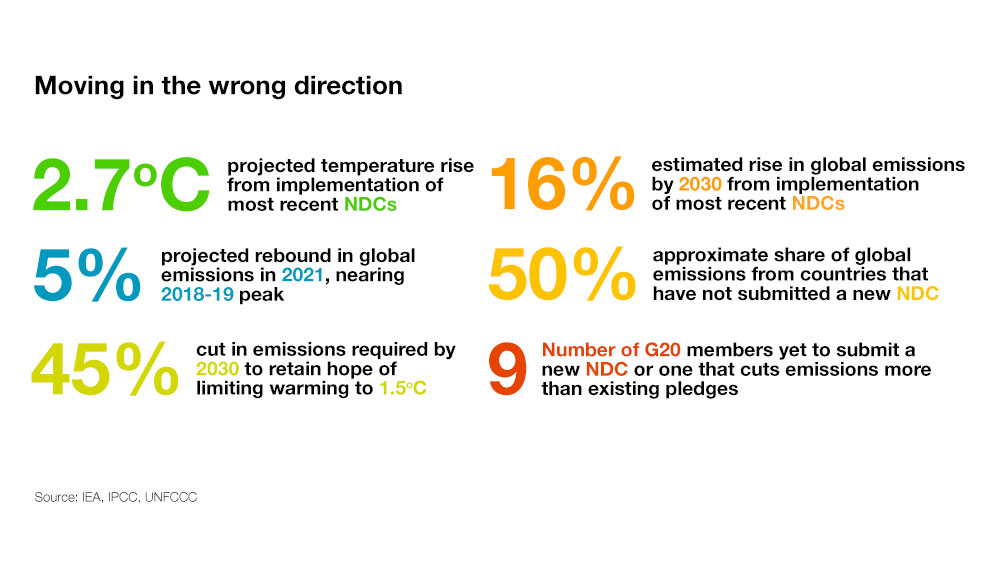

This round of NDCs should outline a roadmap for the coming years up to 2030, and they are the last that parties will have to submit before 2025 (though there is some impetus behind efforts to get countries to submit annual updates). While many governments now have plans to cut emissions to zero by the middle of the century, the scientific community believes that drastic cuts are required much sooner. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) believes that a cut of 45% by 2030 is necessary to keep alive any prospect of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees. Therefore, these pledges and the summit in Glasgow have been billed as the last best chance to stave off the worst effects of climate change. The overarching objective in Glasgow can be summed up as “keeping 1.5 alive”.

Scoring badly

Climate pledges will not be written at the summit (though some may be announced there) and so the success of the attempts to secure emissions reduction pledges consistent with Paris Agreement targets will largely be decided in advance. The UNFCCC on 17 September published an analysis of revised climate pledges issued by the end of July. A total of 113 parties met the revised deadline. According to the analysis, if these pledges were enacted in full, these countries’ collective emissions would be 12% lower in 2030 than in 2010 and represent an increase in ambition from their initial pledges made when joining the Paris Agreement. However, collectively these 113 countries only account for approximately half of global emissions. If all of the most recent NDCs (including from those countries yet to submit revised pledges) were enacted in full, global emissions would rise by approximately 16% by 2030, leading to an estimated 2.7 degrees of warming.

The UNFCCC will publish another report days before the summit to incorporate late additions. The greatest attention will be on the leaders of the G20 who will meet in Rome (Italy) on 30 to 31 October. This group of nations accounts for three-quarters of global emissions. Four G20 members (China, India, Saudi Arabia and Turkey) have yet to publish their NDCs and five (Australia, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico and Russia) have submitted pledges with similar targets to their original ones or that allow for an increase in emissions. China’s NDC is hotly anticipated. However, Beijing is more likely to use the coming weeks to outline a clear roadmap and timeframes for its pledges to reach peak emissions by 2030 and net zero by 2060, rather than bring these dates forward.

COPenhagen 2.0?

While current pledges are still way off the mark, the geopolitical and diplomatic landscapes heading to Glasgow are also inauspicious. Agreement between then President Barack Obama and China’s President Xi Jinping was key to securing an ambitious deal in Paris, but relations between the world’s two largest emitters and economies have soured significantly since then. Although they have moderated since Joe Biden’s inauguration, relations have not normalised. While the Biden administration had hoped to keep cooperation on climate separate from other aspects of US-China relations, Beijing in recent weeks has made clear that climate cannot be treated separately.

The faultline has also widened as the US seeks alliances in confronting China. The timing of a new defence deal between Australia, the UK and the US (AUKUS) has raised particular concern among climate activists who fear it could derail attempts to secure cooperation with China on climate change. Xi has not left China since the start of the pandemic, and AUKUS has cast even more doubt on his attendance in Glasgow. The deal also generates bad blood between the US and UK on one hand and France (a key climate ally) on the other, while rewarding Australia (widely seen as a climate laggard). Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison on 27 September cast doubt on his own attendance, describing it as just “another overseas trip”.

Meanwhile, there are concerns that the UK government (in part because of the COVID-19 crisis) has not made sufficient diplomatic outreach to secure major breakthroughs. In the 18 months before COP21 in Paris, the French government threw the full weight of the French diplomatic corps at the summit.

Hope

Even in 2019 when a global wave of climate activism had increased momentum behind international climate action, COP25 ended in disappointment with few major outcomes and the thorniest issues kicked down the road to COP26.

However, the pandemic aside, much has changed since then. Heading to Madrid in late 2019, only a handful of states had committed to reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions by around mid-century, and US President Donald Trump (having announced Washington’s withdrawal from the 2015 Paris Agreement) was eyeing a potential second term in the White House. Heading to Glasgow, net zero pledges are ubiquitous and (increasingly seen as) a minimum commitment by governments and businesses alike, and Biden has committed to restoring US global leadership on climate change.

Meanwhile, the scientific community has coalesced with even greater certainty around the links between human activity and climate change, and many major emitters are increasingly aligned on the importance of reaching the Paris stretch target. Furthermore, in recent months, unprecedented extreme weather events have hit countries that will be key to ensuring success at COP (including the US and China), shattering the illusion for their populations that climate change is something that exclusively impacts other people.

While a Paris-style breakthrough is unlikely, these factors are likely to ensure some progress on shared climate objectives in Glasgow.