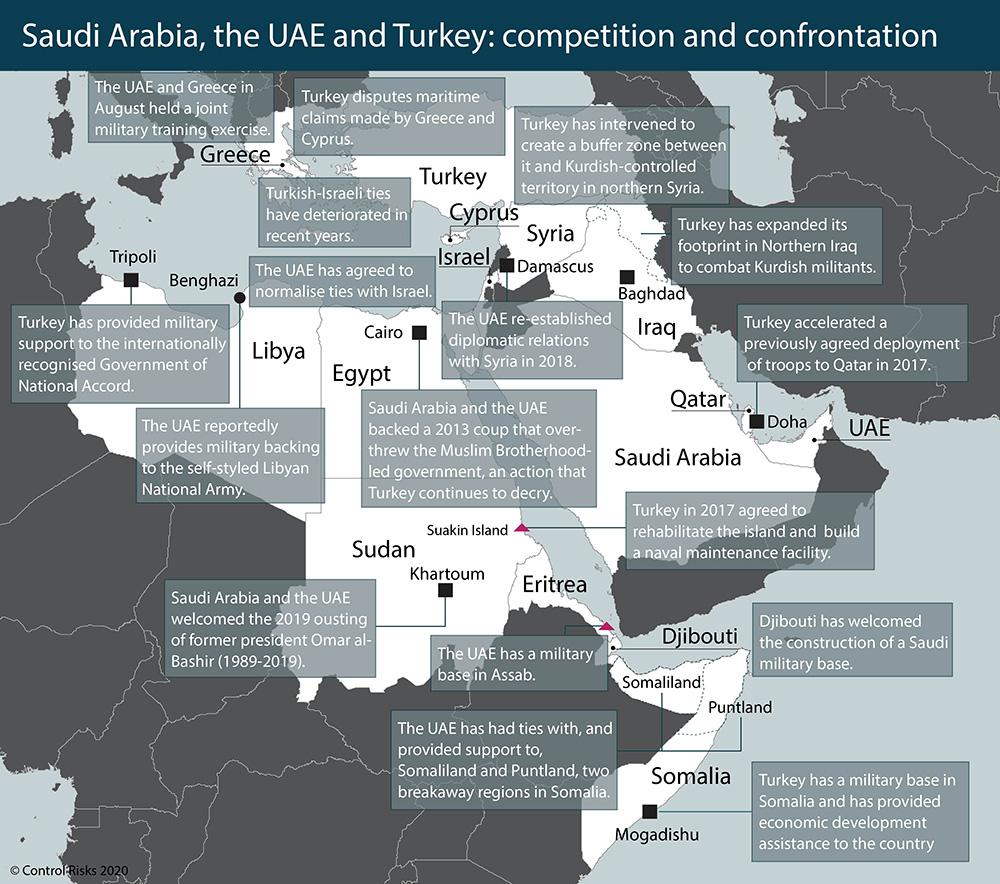

Turkey on the one hand and Saudi Arabia and the UAE on the other have been in confrontation in an increasing number of regional theatres, as they pursue competing projects to shape the region’s future.

- Competition will continue to develop in the public sphere, as both the Saudi-Emirati axis and Turkey seek to mobilise domestic and regional support by appealing to ideology, religion and identity.

- Saudi Arabia and the UAE will increasingly place Turkey alongside Iran as their principal regional adversaries, as they view both as destabilising and revisionist powers.

- Turkey will continue its assertive foreign policy, as it seeks to assume what it views as its rightful place among world powers and the leadership of the global Muslim community.

Background

Deteriorating relations between Turkey on the one hand and Saudi Arabia and the UAE on the other have been playing out in a public war of words. In July, Turkish Minister of Defense Hulusi Akar claimed that Abu Dhabi was harming Ankara’s interests and that “at the right place and time, accounts will be settled”. UAE Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash retorted that Turkey should stop its colonialist interference in Arab affairs.

Both sides seek to support the military and financial power they deploy to various regional theatres but also attempt to draw on historical legacies to frame these clashes and garner domestic and regional public opinion. In 2017, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and UAE Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan traded cutting remarks over the Ottoman Empire’s actions in the Arabian Peninsula. Saudi Arabia subsequently pulled Turkish TV series and revised its history curriculum to highlight resistance in the peninsula. There have been social media campaigns in the kingdom calling for boycotts of Turkish goods and Turkey as a holiday destination.

Underlying these wars of words and cultural clashes lie two competing visions. Saudi Arabia and the UAE on the one hand and Turkey on the other have increasingly depicted the other camp as rivals.

Gulf grievances

Saudi Arabia and the UAE have embarked on a more interventionist foreign policy since the 2011 Arab uprisings. The perception of the threats posed by political Islam and Iran to regional stability has driven such interventionism.

The two countries found themselves opposed to Turkey regarding political Islam. Turkey – and Qatar – saw Islamists in ascendance after 2011 and viewed the Muslim Brotherhood’s assumption of power in Egypt and Tunisia as an opportunity to expand Turkish influence, given the Islamist roots of the ruling Justice and Development Party (known by its Turkish acronym AKP). Conversely, the two Gulf states saw the Muslim Brotherhood as a regionwide ideological movement that could threaten stability.

The Saudi-Emirati view of Turkey has hardened in recent years. They saw Ankara’s move to back Doha against the Saudi- and Emirati-led boycott in 2017 as intervening in a Gulf dispute and Turkey’s establishment of a military presence in the emirate as provocative and a national security threat. Turkey’s attempt to exploit the 2018 murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul by Saudi state agents confirmed the Emiratis and Saudis’ perception of Turkish hostility. Erdogan was seen as attempting to use the murder to oust Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman bin Abd al-Aziz Al Saud (known as MbS).

Turkey has increasingly competed with Iran as the two Gulf states’ principal regional rival. Gulf news outlets depict Turkey as being driven by a combination of Ottoman revanchism, what they see as Erdogan’s megalomania (backed by Qatar) and drawing on and supporting an extremist Islamist ideology.

The two countries’ critique of Turkey parallels their objections to Iran: both are seen as non-Arab interlopers that seek to mobilise transnational and sectarian ideologies and identities and work via non-state actors to exploit the Arab state system. In contrast, the two Gulf states depict themselves as committed to preserving prevailing state structures and the security architecture in the region while prioritising economic development over political reform.

Turkey’s take

In Turkey, the UAE and Saudi Arabia are increasingly portrayed – particularly within the pro-government press – as antagonists seeking to undermine Turkey.

Turkey has grand foreign policy ambitions and in recent years demonstrated a willingness to project power and act unilaterally to achieve its goals. Turkey’s approach is driven by both pragmatic immediate concerns, such as border security, and future, more abstract goals of establishing itself with independence on the world stage and reducing its vulnerability to shifting global and regional geo-politics.

Turkey’s government seeks to place its foreign policy within a moral narrative to secure domestic support and shape regional publics’ perceptions of its actions. Turkey is both claiming to act as a force for good by supporting the democratic aspirations of its Muslim neighbours and take a place on the world stage proportionate to its self-perceived military, economic and cultural power. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are portrayed as clashing with Turkey due to their support of a depoliticised form of Islam and reactionary opposition to democratic Islamist movements.

Turkey is unlikely to alter its foreign policy without a major shift domestically. Its assertive stance sits well with nationalist voters, on whom the government has become increasingly reliant, while its pan-Muslim world rhetoric attracts Islamist voters.

Turkey believes that it is seeing the returns of its assertiveness: its intervention in Libya has provided it with a new ally in Eastern Mediterranean maritime disputes; Somalia has invited Turkey to explore oil in return for Turkish military and economic support; and Turkish retail products have grown their market share in North Africa. In Syria, Turkey has become a key arbiter of the country’s future alongside Russia and Iran while countering the Kurdish independence movement, which Ankara sees as a national security threat.

The rivalry with Saudi Arabia and the UAE has proven to be a useful addition to Turkey’s moral framing of its foreign policy. Ceding to Saudi Arabia and the UAE would curtail Turkey’s ambitions and be politically costly domestically.

Power plays

There is little prospect for reconciliation between the two sides over the coming year. Turkey’s intervention in Libya this year and the UAE’s recent entrance to Eastern Mediterranean power dynamics have exacerbated already tense regional relations. Both sides will likely remain involved in areas where the other desires to project influence and entice leaders with investment deals.

The rivalry will play out in the West where the UAE’s arguably greater diplomatic leverage will counterbalance Turkey’s strategic – but increasingly troubled – ties with the EU and the US.

All three countries face economic difficulties due to the COVID-19 pandemic – Turkey had pre-existing economic challenges. They could take dramatic measures on the world stage to change their fortunes, such as a Turkish attempt to forcefully secure access to gas reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean.

As the US continues to adjust its presence in the Middle East and relationship with some of its traditional allies, both sides have demonstrated a willingness to go against the grain of the established international order and “go it alone”, pursuing a unilateral approach. This rivalry will likely play out over more issues and lead to increased military involvement in ongoing and future conflicts.