Two questions lie at the centre of what the global COVID-19 pandemic means for supply chains.

Has there ever been a moment when the global economy was more interconnected?

And, has there ever been a moment when every company in the world was in crisis at precisely the same time?

The answer to both is “probably not”. Like nothing before it, the pandemic has stopped us at our borders and in our board rooms.

Months of commerce-crushing lockdown, followed by a deeply fragmented exit from the acute phase of the pandemic, will continue to wreak havoc on supply chains. On some level, every company understands that, sooner or later, the physical gridlock of lockdown will ease. But as that process grinds haltingly forward, other equally critical concerns loom.

Our experts explain some of the political and practical concerns surrounding post-pandemic supply chains, and suggest where companies can identify, manage and mitigate those issues.

The politics

The resilience test that is COVID-19 will play a critical role in re-shaping business practices, government regulations and customer preferences long after the pandemic is brought under control. Some signs of these changes are already visible.

Governments are signalling their intent to tighten regulation to protect vitally important sectors from future disruption. Rising geopolitical tensions between China and the US could result in new rounds of trade wars and increased hurdles for foreign investment. Efficiency and resilience – not just cost and flexibility – will become new supply-chain mantras.

Regulatory risk on the rise

Changing government regulations pose one of the most significant long-term threats for companies with global supply chains. These threats stem from the fact that regulatory changes will happen simultaneously in countries around the world but will not be joined up at all. To make matters more complex, companies must anticipate that these changes will largely not be driven by market efficiency or global trade consideration. Instead, many will be driven by fracturing domestic politics and increasingly contentious geopolitics. This runs counter to the borderless world that commerce has sought to build over the past two decades.

As the post-pandemic economic crisis deepens, governments around the world are putting together national rescue plans. In some cases, these include taking equity stakes in large industrial and other systemically important companies. The beneficiaries of these bailouts will likely face demands to re-focus their business strategies from deriving global cost effectiveness towards creating jobs and delivering technological innovation at home.

This trend towards rising economic nationalism – by re-shoring or on-shoring manufacturing supply chains – was evident long before the crisis. The pandemic has accelerated and mainstreamed these ideas across the majority of developed market economies.

- The US under the Trump administration will coax, cajole and maybe even coerce companies to cut their addiction to the single dominant supplier – China.

- The EU will, for the foreseeable future, seek to direct investment toward projects that brings supply chains home.

- Developing countries – particularly those in Southeast Asia – will seek to consolidate the victories globalisation gave them. This part of the world will not easily relinquish its prominent position in global supply chains.

Companies will need to remain vigilant for, and sensitive to, these changes. They must adopt internal mechanisms to identify, among other things, the following divergent trends:

The key question for policymakers is: Does re-shoring or on-shoring supply chains make them stronger, or does it replace one sort of dependency with another? For many companies, the key solution to their post-COVID resilience concerns will be to ensure supply chain diversification.

Perhaps the other question – for policymakers and companies alike – is “will it work?” Companies initially moved their supply chains overseas for cost considerations. And, while that factor remains prominent, many companies now manufacture internationally to service those more distant markets. In some emerging markets, in fact, domestic production is now a condition for market entry. If your home market forces you to go home, your international markets may say “don’t bother coming back.”.

The brute geopolitics

The rise of economic nationalism coincides with the already fragile state of the global free trade system. Finding a new global consensus in support of the open trade regime will be extremely difficult, even if the White House has a new occupant following the US presidential elections.

In the coming years, companies will have to stress test their supply chains against the threats of rising protectionism, the exacerbation of trade wars, and increased government scrutiny of foreign investments and foreign business activity. This is particularly the case in more strategically sensitive sectors – the list of which has grown considerably during the pandemic.

- To prevent foreign investors from accessing sensitive technologies and data.

- To ensure that foreign investors do not control vitally important elements of the economy.

- To prevent national champions affected by the current economic crisis from being taken over by foreign capital.

The screening of inbound foreign investment was becoming an increasingly important government tool prior to COVID-19. The current crisis is set to make its applications even more extensive. The screening has three objectives:

Governments usually screen FDI in the so called “strategic sectors” of their economy. Before the pandemic they included dual-use (civil/military) technologies, IT and telecommunications. After the pandemic, the list will expand significantly and include the health sector, pharmaceuticals, biotech and potentially even elements of food security.

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) has long been screening all foreign investments in US companies or operations against national security concerns. The process can be lengthy, and its decisions are not transparent. Now, the US Congress wants to take steps to ensure that the US pharmaceutical sector, including prescription drugs and health products, is less reliant on China.

In Europe, screening is now being undertaken at both national and EU levels, making these procedures lengthy and costly. In countries like Russia and China, extensive foreign investor screening is likely to tighten and become opaquer.

Let us not forget another popular government protectionist tool, sanctions. Sanctions have been a major disrupter of supply chains, along with trade wars and traditional security threats. The COVID-19 pandemic opened the door to the application of sanctions on health policy grounds.

Evolution, not revolution

Fear not. Or at least, not too much. Despite the political rhetoric around supply chain issues, changes in business practices and government policies will be gradual and come with opportunity. We face not a revolution in global supply chains, but rather an organic evolution.

We were already heading in this direction. The pandemic has primarily served to accelerate and mainstream many existing policies and trends. Companies were already taking steps to diversify their supply chains from the overwhelming dependency on China. Increased foreign investor screening and rising protectionism were already hallmarks of the Trump Administration; copycats were already taking root elsewhere.

Navigating roadblocks you can see

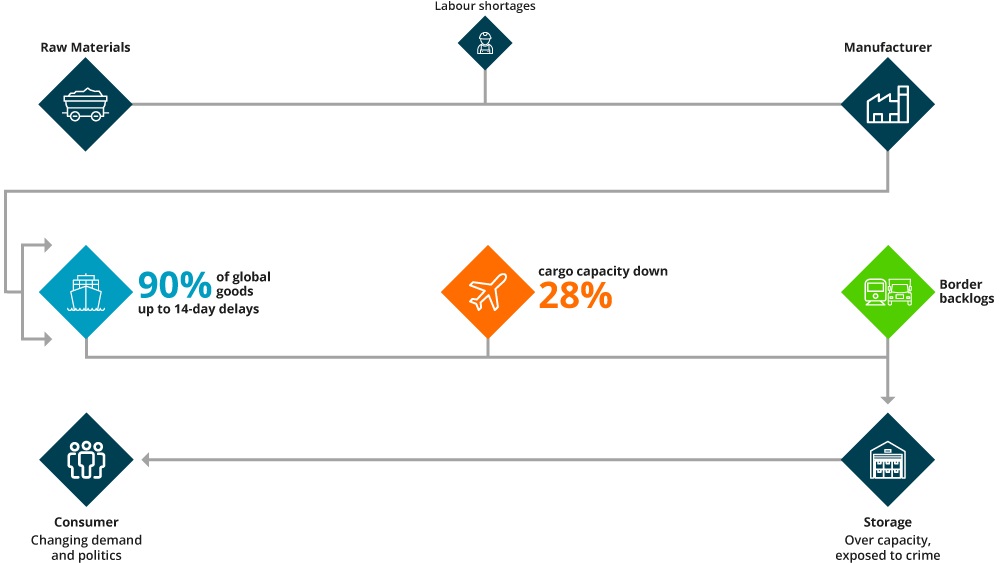

- The major transport modes of aviation, rail, road and – most of all – shipping will continue to face delays at border points, keeping supply chain lead times up to 75% longer than pre-crisis levels. The onus will be on operators to innovate and adapt, rather than wait for government action.

- Supply chains will be exposed to security issues in the hardest-hit developing economies while demand fluctuations will push warehousing and storage in Europe to capacity, exposing supply chains to theft and organised crime.

- The reconstitution of supply chains will force companies into the arms of completely new third parties – and their associated risks. Bear in mind though, supply chain diversification presents an opportunity to bring long-term resilience against future crises.

So much for the boardroom navigating the global patchwork of politics and protectionism. Here come the immediate roadblocks – the kind that will literally stop your truck at a border checkpoint.

A port bottleneck

A sophisticated transport network underpins almost everything we consume. This supports the ability to move raw materials mined in Africa to a manufacturing plant in Asia to consumer markets anywhere in the world. The network, which connect the chains, relies on the ability of those goods (and the people moving them) to seamlessly cross borders. The COVID-19 pandemic has not so much broken the chain, but severely disrupted the network by introducing government restrictions that hamper that seamless movement.

High costs

Such ambitious transformation projects come with very high realisation costs. NEOM has an estimated cost of USD 500bn. The country also has plans to transform the capital Riyadh into an economic, social and cultural hub by 2030 at the cost of USD 800bn. Several other multibillion projects are planned to be completed by 2035. Although the authorities count on attracting foreign investors to participate in the development of parts of these projects, the financial burden on state finances will be daunting, particularly at a time of low oil prices.

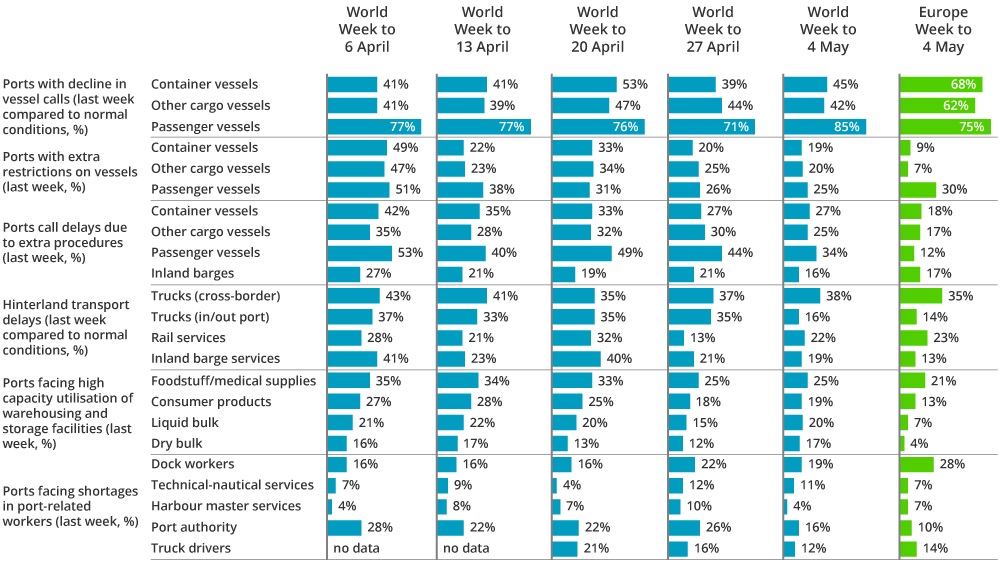

We believe many governments will move toward easing restrictions on the maritime community, including implementing a framework of protocols recommended by the industry. Progress is likely to remain globally inconsistent for the rest of the year; industry effort and cooperation will continue to be critical.

Aviation

Passenger aircraft usually carry additional freight in their cargo holds, which constitutes about 28% of global air freight . The grounding of the majority of these aircraft during the pandemic has created a backlog for goods wanting to shift to the purely cargo-bearing air fleet. That logjam comes even in the face of sharply decreasing consumer demand.

Airlines are adjusting to alleviate the bottleneck, but FMCG supply chains, among others, will continue to face delays in the air and increased freight rates: Shanghai-Europe rates have already increased 340% year-on-year, and Shanghai-North America rates by 272%. Electronic, seafood and luxury goods have been hit particularly hard by the trend, which will persist while passenger traffic remains severely restricted. The slow resumption of passenger traffic will ease, but not immediately resolve, the cargo capacity problem.

Rail/Road

Rail freight was making a comeback pre-COVID-19 and is quickly absorbing air freight in an attempt to ensure essential and FMCG supply chains. It represents a viable alternative for those supplies stuck in the aviation bottleneck but cannot come close to compensating for the crisis in the maritime sector.

Planes, trains, automobiles… and data

Managing personal travel during the pandemic has been pretty easy: in most cases, don’t. Goods are another story. The complexity of the transportation matrix above is a significant challenge to even the most sophisticated companies and their logistics partners.

Fortunately, challenging situations in these modern times do us one great favour: they create a lot of data. Almost any company can now have the tools to extract that data and make it meaningful to them.

Some of the most important analytics to extract from your supply chain data is the resilience of both suppliers and customers. Which of your partners is getting you inputs fastest? Which of your customers is seeing a spike in demand? How vulnerable to external shocks are both of these critical partners, and what might those shocks look like?

These are difficult, but not impossible, questions to answer. They require only two things – speed and firm decision-making. The global environment for supply chains may be evolving; your company’s supply chain may not have that much time.