The rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus from Wuhan in China to more than 200 countries by the end of March has had a dramatic impact on companies and their employees worldwide. The business continuity and economic challenges of the pandemic are being well documented as the situation evolves. Special Risks like kidnap and extortion may be a small subset of many companies’ concerns right now, but they are still present and evolving during the crisis.

The majority of infections are currently in business hubs and economic capitals across Asia-Pacific, Europe and North America, with the virus yet to fully take hold in the world’s kidnapping hotspots and conflict-affected environments. The impacts on the kidnapping and extortive environment are therefore different in heavily affected areas to those still awaiting an uptick in infections. Here we assess the Special Risks trends businesses need to be aware of now, and what scenarios they should consider for the future.

Immediate impact of COVID-19 on Special Risks

Wherever there is a crisis, criminal groups find ways to capitalise. Crisis management teams (CMTs) are having to grapple with questions about how to safeguard the health of their people while simultaneously dealing with a range of virtual and physical threats to their employees.

Opportunistic criminals were the first to develop new ways of using the COVID-19 pandemic to their extortive advantage. Before the lockdown was imposed in France, criminals posing as police officers and health workers issued fraudulent “fines” of EUR 150 to people wearing facemasks, which violate a 2010 law prohibiting the covering of one’s face in public places.

Then, as people began to keep off the streets in locked down countries the extortive market moved online. Cyber extortionists have found ways to exploit vulnerabilities as people become more anxious and more isolated. Increases in phishing campaigns and ransomware attacks using seemingly genuine websites or links providing information on COVID-19 are being used to infect computers, extract user credentials and elicit payments for fake goods such as masks, hand sanitisers, medicines and most recently, fraudulent offer of free COVID-19 test kits.

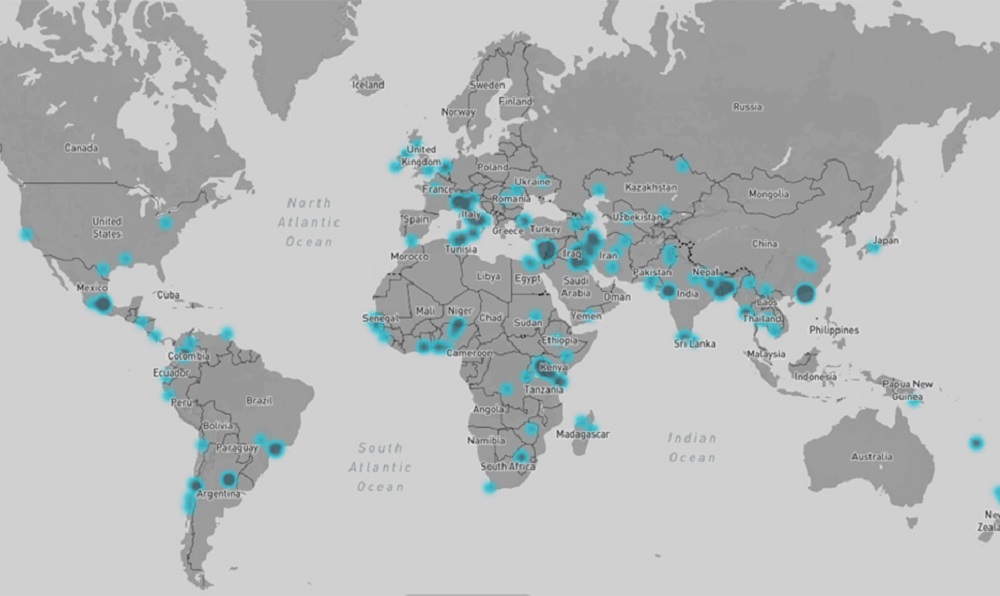

As the first cases of COVID-19 were reported in Latin America and Africa, this added another physical threat to CMT agendas: xenophobic violence and COVID-19-related threats to European, North American and Asian workers. In Mexico and Madagascar the public release of the positive test results of international workers for COVID-19 has led to threats against their safety from people who accurately guessed the identity of the infected expatriates in their communities. In Ethiopia and Cameroon, government officials and US embassy representatives have both warned of an uptick in violence and threats to foreign nationals, especially those of Western or East Asian appearance. Anti-foreigner sentiment has been expressed through stone-throwing, hitting cars, refusing access to public transport, and verbal and online abuse. COVID-19-related security incidents such as civil unrest and crime have been recorded all over the world.

Source: Seerist

While head offices in major cities across the world may be consumed with COVID-19 crisis planning, the threat of kidnap-for-ransom and other forms of extortive crime to their global operations continues unabated. Control Risks’ data for Mexico, Nigeria and India, three of the world’s kidnap-for-ransom hotspots, show that incident numbers in the first quarter of 2020 held steady in Mexico and increased by 30% in Nigeria and 50% in India compared with the same quarter last year. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador on 3 April announced that violence between organised crime groups has persisted despite the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. Under these conditions, CMTs may find themselves forced to deal with a serious and complex risk-to-life situation at a time when they are already severely stretched.

Outlook as COVID-19 hits kidnapping hotspots

As the COVID-19 crisis takes hold in the world’s kidnapping-for-ransom hotspots, it has begun to suppress abduction rates as people go into lockdown, reducing the potential victim pool for kidnappers. Many kidnapping groups abduct people from the street rather than their homes as it is easier for criminals to target victims opportunistically while they are vulnerable. In addition, the crisis is likely to hit household incomes across the socio-economic spectrum, reducing the ransom amounts that people are able to pay. Global GDP projections for the COVID-19 crisis suggest that countries may experience a 5%-10% contraction year-on-year as the initial economic shock caused by reduced economic activity and increasing sickness develops into a long-term economic crisis.

We have seen similar conditions before, albeit not as a consequence of a global pandemic. In Venezuela, an estimated 15%-19% of the population (some 4.7m-6m people) is thought to have left the country since the economic and political crisis began in 2012. Those who remain have seen GDP fall by 79%, hyperinflation hit 10,000,000% and the average family’s access to cash dwindle. Control Risks’ data shows how rates of kidnapping-for-ransom have dropped as the economy has contracted and the population declined, with incident numbers in 2019 around a third of where they were in 2012.

As profits from kidnapping reduce, criminal groups look to diversify their activities. In Venezuela, Control Risks recorded a spike in extortive crimes such as threat extortion, cyber extortion and illegal detention in the country, even as kidnapping declined. These forms of extortion can be more accurately targeted at those parts of society more likely to retain access to funds than the general public, such as successful businesses and high-net-worth individuals. The threat is compounded by the fact that these individuals often have a visible public profile and their names may be widely associated with their company’s operations.

In addition, although overall kidnapping levels have declined, groups have not stopped kidnapping altogether. Some have adapted their tactics to maximise profits despite the smaller victim pool and the limited ability of many families to pay high ransoms. For example, since 2012 the average duration of kidnaps has dropped by 41% nationwide, and groups often accept high-value items such as jewellery and vehicles as part of ransoms. Most incidents in the capital Caracas are now resolved in hours rather than days, allowing groups to make money quickly even if the profitability of the crime has decreased significantly.

As COVID-19 hits the kidnap economy, criminal groups will remain highly motivated to maintain their income levels. High-capability groups may be able to refocus their kidnapping operations on seizing victims from protected locations such as residential compounds or secure worksites. Those that cannot, will likely adopt new tactics to maximise profits in uncertain times, including diversifying towards other forms of extortive crime like threat extortion, virtual kidnapping and cyber extortion. They will also continue to kidnap victims in areas where lockdowns are less successful in keeping people off the streets, for example because enforcement is weak, or in rural areas that are less affected by the crisis. However, overall levels of kidnapping will nonetheless remain depressed.

As soon as lockdowns are relaxed and economic activities begin to recover, groups will very quickly resume their activities. Rates of kidnap may even exceed previous levels as criminals attempt to recoup as much cash as possible in the early days of economic recovery. Control Risks’ data from the first quarter of 2020 shows that incidents in Venezuela increased by one-third compared with the last quarter of 2019. The country since early 2020 has informally adopted a dollar economy, meaning that more money is circulating through small businesses and households again. This demonstrates the speed at which kidnapping rates can rebound even before countries achieve a full recovery.

Outlook as COVID-19 hits fragile and conflict-affected states

Although countries such as Mexico and India might see a short-term fall in kidnapping rates during the COVID-19 pandemic, countries that are already grappling with high levels of instability or armed conflict such as Iraq, Libya, Mali and Syria are unlikely to see similar decreases. COVID-19 will draw security forces away from tackling criminal and militant groups and towards enforcing curfews in urban areas. This will create a security vacuum that could increase kidnapping rates both immediately and in the longer term.

Despite announcements of a coronavirus-related “humanitarian pause” by combatants in Libya, proposed ceasefires by separatists in western Cameroon, the Saudi-led Coalition in Yemen and the National Liberation Army (ELN) in Colombia, pledges to avoid military engagement by the Syrian Democratic Forces and agreements to halt fighting in the Philippines, the outlook for conflict-affected states as COVID-19 numbers rise is bleak. Terrorist and criminal groups can quickly capitalise if state resources and attention are redirected elsewhere. Control Risks is already seeing such a scenario in Iraq as the number of kidnaps conducted by Islamic State (IS) begins to rise again after a significant decline, enabled by the redistribution of Iraqi forces to enforce lockdowns in the capital Baghdad. Comparably, IS in Afghanistan is likely to benefit from a similar movement of forces away from its strongholds in the east to reinforce those in the capital Kabul.

In addition, Control Risks’ data for previous global health emergencies suggests that underlying insecurity creates a permissive environment for kidnapping and disease to spread together. This was the case in Congo (DRC), which declared the tenth outbreak of Ebola in 40 years on 1 August 2018. With a total of 3,453 cases confirmed by 30 March 2020, it was the country's largest Ebola outbreak and the second-largest Ebola epidemic ever recorded, behind the West Africa outbreak of 2014-16. High levels of ongoing insecurity, including the kidnapping of aid workers deployed to provide healthcare to communities, complicated efforts to contain the crisis.

50% of kidnapping incidents recorded by Control Risks in the DRC during the first quarter of 2020 have been local medical workers.

Control Risks’ data for Congo suggest that where infection and poor security provision collide, rates of kidnapping can rise dramatically throughout the course of a health emergency. Criminals and armed groups can capitalise on increasing impunity in the early phases of a crisis and can sustain high levels of kidnap even after the infection is brought under control because security in these areas is weakened in the long term. This was the case during a smaller-scale Ebola outbreak in Congo in 2012-14, when the rate of kidnapping increased by 92% between the start and end of the outbreak and did not fall again until 2016.

It is difficult to separate the impact of Ebola on kidnap rates in Congo from the negative effects of widespread insecurity in the country that pre-date the health crisis. However, the direct impact of Ebola on the kidnap risk in some sectors is easier to establish. Health emergencies can lead to an influx of foreign nationals and aid money into fragile environments, and aid workers providing critical first response relief can be particularly vulnerable to kidnap by both criminal and armed groups, which are able to operate with relative impunity in many of these areas. Kidnapping groups in Congo have repeatedly targeted frontline workers such as medical and health staff as a direct result of their efforts to contain the spread of Ebola. During the most recent outbreak, an international aid agency suspended some of its programmes to counter Ebola after gunmen in February abducted two local staff members for two hours. Meanwhile, persistent insecurity means that some victims can experience long periods in captivity. During the 2012-14 Ebola outbreak, four employees of an international aid agency were abducted while they were assessing the medical needs of villages in North Kivu province. In August 2014, one of the captives successfully escaped, but no news has been received of the remaining three victims.

In the short term, conflict-affected countries will be less able to enforce lockdowns and curfews than their more stable counterparts. They are therefore unlikely to see the same sort of decline in kidnapping that we are beginning to see in other global hotspots. In the longer term, breakdowns in security provision, heightened civil unrest and significant loss of income as the virus spreads will likely sustain high kidnapping rates. These conditions will create a challenge for businesses, particularly in sectors on the frontline of the crisis such as healthcare, pharmaceuticals, aid and development, but also in oil and gas, manufacturing and other sectors with operations in countries such as Iraq and Libya.

Conclusions

The ongoing crisis across Asia-Pacific, Europe and North America is providing criminals with entirely new opportunities, both physical and virtual, to target employees and businesses. At the same time, companies are likely to have to respond to a complex and life-threatening crisis unfolding in a kidnap hotspot not yet fully affected by COVID-19.

Looking ahead, the spread of the pandemic into these hotspots will see new groups emerge and established players adopt new tactics, posing challenges for businesses. This will force companies to closely monitor and re-evaluate the threat to their people, projects and presence around the world. Elsewhere in conflict zones, a different trajectory will unfold, with high kidnapping rates likely to persist throughout peaks in infection.

Looking even further ahead, as soon as the conditions for kidnapping rebound, groups will scramble to improve their cashflow through increased kidnapping activities. COVID-19 may see the emergence of criminal and armed groups that have exploited reduced security force pressures to become more powerful and adaptable. It is essential that businesses return more prepared, more resilient and ready to meet that challenge.