- QAnon will continue to expand its following in the US and other Western countries in the context of COVID-19.

- QAnon will not seriously undermine political stability, though it is likely to further polarise political debate in some countries – particularly in the US ahead of the November 2020 elections.

- Conspiratorial narratives will remain a common feature of anti-lockdown and anti-vaccination protests in Western nations, particularly as restrictions are extended and – in some cases – tightened.

- Although the vast majority of believers are not inclined to engage in violence, precedent and the overlap with other conspiratorial ideologies suggest that QAnon is likely to inspire isolated acts of violence.

Q

QAnon emerged in 2017 when an anonymous individual using the moniker “Q” – a reference to a US government security clearance – began posting cryptic messages on niche online message board 4chan. Q – who is now likely to be several different people – claimed to be a US government insider with classified information about the administration of US President Donald Trump. Rather than a single conspiracy theory, QAnon is a nebulous collection of interweaving narratives, most of which have developed from other previously debunked theories. Essentially, QAnon’s believers think that Trump is leading a power struggle against purported “deep state” actors. Among other issues, they commonly assert that members of the media, business community and US Democratic Party are engaged in a range of nefarious activities such as human trafficking, paedophilia and the harvesting of a life-boosting chemical from the blood of children.

Interest in QAnon has expanded significantly since 2017. Widespread familiarity with many of the existing conspiracies that it draws upon has likely helped its spread. While Q “drops” first appeared on 4chan and then migrated to 8chan (now 8kun), their main narratives currently circulate on mainstream platforms and receive increasingly widespread media attention. This has doubtless broadened QAnon’s appeal with an older and typically less digitally savvy demographic.

Its following has grown significantly with the spread of COVID-19. This is not coincidental. Research has shown that conspiracy theories tend to flourish during periods of upheaval and crisis as they can provide believers with a way to understand and explain an increasingly uncertain world. The intense levels of misinformation and disinformation about COVID-19 – not to mention the significant gaps in our scientific understanding of the virus and how to combat it – have created fertile terrain for QAnon.

Q’s posts contain “crumbs” of intelligence that purport to guide followers to discover further “truths”. The fact that QAnon constantly develops new narratives and encourages followers to decipher events around them has helped it to cross-pollinate with other conspiracy theories that began circulating soon after the outbreak of the virus. Pandemic conspiracists have particularly pushed theories about the pandemic’s origins: that it was planned, that it was manufactured in a laboratory, and that fifth generation (5G) wireless technology and infrastructure have contributed to its spread. QAnon and COVID-19-related conspiracy theories have now become mutually reinforcing.

Global spread

Before 2020, QAnon was almost unheard of outside the US. As well as helping it to grow within the US, the pandemic has helped it spread overseas. The imposition of COVID-19-related restrictions on all aspects of life has led people globally to spend more time online, particularly on social media. This has likely helped introduce QAnon to a wider, international and – in some countries younger – audience. In recent months it has gained followers in other English-speaking countries, including the UK, Canada and Australia. QAnon-related social media groups in French, Spanish, Hungarian, Italian, Russian and Czech have helped it to gain significant traction across Europe. One of its largest followings is now in Germany.

Although the general thrust and tone of QAnon are similar in all countries, its global network of followers has also moulded its themes to local political and social conditions. German followers claim that Chancellor Angela Merkel is a “deep state puppet”. QAnon accounts in France have targeted President Emmanuel Macron, and in Italy Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte. Meanwhile, in the UK some followers allege that Q “installed” Boris Johnson as prime minister.

Prominent public figures with large online followings have helped to promote QAnon to their followers and have likely given it further legitimacy. In June, a high-profile British musician gave an interview in which he queried whether there was sufficient evidence to debunk aspects of the Pizzagate conspiracy theory – a predecessor to QAnon that has been co-opted by the movement. This theory asserts that senior members of the US Democratic Party (including former presidential candidate Hillary Clinton) were involved in a child sex trafficking ring run out of a pizza restaurant in Washington DC.

Political ripples

Although when QAnon has been acknowledged in political circles it has largely been dismissed, it is influencing debate on the margins. There is no political ideology underpinning QAnon, and some believers fall on different sides of the political spectrum or are otherwise apolitical. However, the movement’s theories appear to play best with the right and have particularly overlapped with other right-wing conspiracies.

In May, independent Italian politician Sara Cunial gave a speech in parliament in which she promoted theories that had been popularised by QAnon’s believers. However, given its origins and deeper penetration in the US, QAnon is having the greatest political impact in that country. Many of its followers stood in primaries for the November 2020 Congressional elections, and several will appear on the ballot. Although most are almost certain to lose, at least one is likely to be elected to the US House of Representatives. Marjorie Taylor Greene – the Republican candidate for Georgia’s 14th congressional district – is running in a reliably safe Republican seat and has described QAnon as a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to take this global cabal of Satan-worshipping paedophiles out”.

QAnon is also attracting the support – tacit or otherwise – of existing politicians or political figures. In July, former US National Security Advisor Michael Flynn posted a video online in which he recited an oath with slogans linked to the QAnon movement. Although many politicians have distanced themselves from the movement, it is possible that some have maintained a more ambiguous stance as they seek the electoral support of its followers. Before his Republican Congressional primary in July, former US Attorney General Jeff Sessions circulated a QAnon internet meme that had been popularised in 2018 when he was still in post. US President Donald Trump has also been accused of giving tacit support to the movement, and many QAnon members are visible at rallies in support of the president.

Taking to the streets

As QAnon’s support base has dovetailed with that of other conspiracy theories relating to COVID-19, its followers have appeared with growing frequency at demonstrations relating to the pandemic and ongoing restrictions on personal liberties. Supporters brandishing signs with common QAnon insignia (such as #SaveTheChildren and #WWG1WGA) appear side-by-side with anti-vaccination, anti-mask and anti-lockdown advocates.

To date, these protests have mostly been small and peaceful, and have not caused significant disruption, though some have drawn larger crowds. In Berlin (Germany), approximately 38,000 – some adherents of QAnon – on 29 August took part in a protest against COVID-19-related restrictions. With infection rates remaining high or rising again in many of the countries where QAnon is gaining support, restrictions are likely to remain in place or be tightened over the coming months. As well as adding to the conditions that have helped the QAnon conspiracy theory to spread, this situation is likely to prompt further protests involving its supporters.

The potential for violence

Followers have engaged in malicious targeted activity online, including by doxing individuals that they believe to be associated with the “deep state”. The vast majority of QAnon’s supporters are not inclined to engage in malicious violent activity offline. Unlike extremist ideologies, QAnon does not actively promote violence. Furthermore, it is a diffuse movement that lacks the kind of structure required to orchestrate violence in a coordinated and sophisticated way.

However, in May 2019, an FBI intelligence bulletin identified “conspiracy theory-driven domestic extremists” as a growing threat, specifically mentioning QAnon. In July 2020, also referencing QAnon, Twitter released a statement saying that it would take strong action against “behaviour that has the potential to lead to offline harm”. In the same month, it removed more than 7,000 accounts relating to the movement, and reportedly imposed restrictions affecting approximately 150,000 others. QAnon’s evolution and the incorporation of new narratives will likely make this content more difficult to moderate.

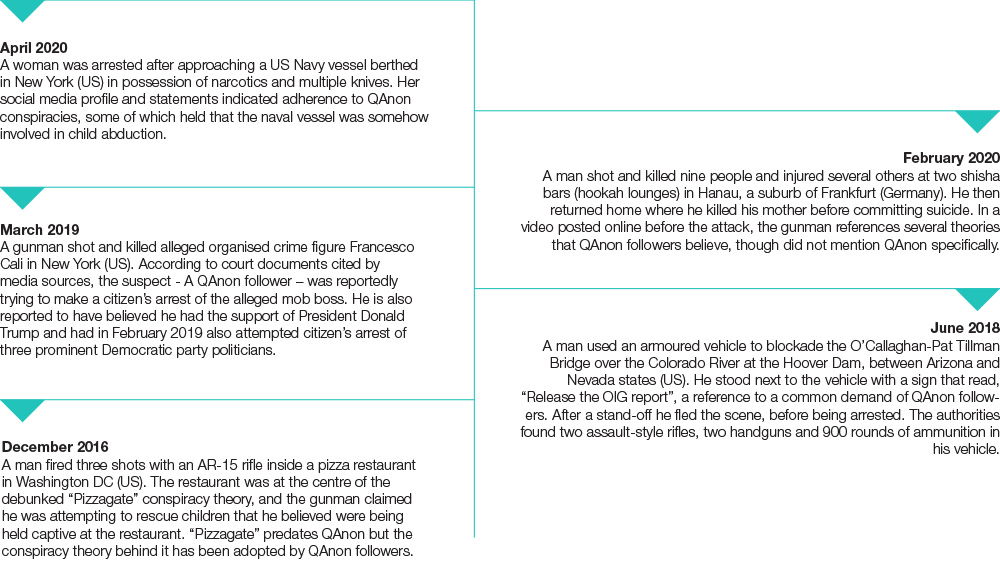

Incidents or threat of violence perpetrated by individuals with links to QAnon

Precedent has shown that QAnon’s polarising and divisive rhetoric is likely to inspire or incite individuals operating alone to carry out isolated acts of violence. In particular, the movement’s central focus on child abuse appears to be one of the themes most likely to inspire violence. In online interactions, believers have occasionally floated the idea of violence when fixating on the issue, which is often discussed in salacious detail.

The leaderless nature of the movement also means that the actions of radicalised believers cannot be easily controlled or condemned. Right-wing conspiracy theories circulated online have contributed to the rise in right-wing extremism in the West in recent years. More recently, anti-5G narratives have led to attacks on telecommunications infrastructure. QAnon’s cross-pollination with these and other conspiracies will likely reinforce the threats that they already pose in North America, Europe and Australasia. QAnon conspiracies may also overlap with or reinforce existing personal grievances or stresses.

The target profiles of any future attacks are likely to be informed by the continued evolution of the conspiracy theory’s narratives. They are likely to include the typical targets of right-wing extremists such as government assets, left-leaning politicians or activists, and racial, religious or ethnic minorities. However, precedent suggests that there is the potential for believers to engage in acts of misguided vigilantism against targets they believe to be involved in child abuse. The interpretation by individual radicalised followers of the various conspiracy theories popularised by QAnon is therefore likely to add a layer of unpredictability to potential attacks.