Several high-profile economic interventions in recent months signal a government struggling to address growing macroeconomic and political instability, and are driving unprecedented levels of uncertainty for businesses.

- The central bank’s numerous changes to monetary policy over the past year indicate its ongoing inability to strengthen the local currency (Zimbabwean dollar – ZWL) and reduce hyperinflation.

- Meanwhile, its targeting of private businesses signals that it is seeking to scapegoat external actors for macroeconomic challenges.

- Businesses will face an ever more hostile environment for their operations amid growing uncertainty around the security of their investments.

- Political stability and civil unrest risks are also growing as the government adopts increasingly repressive measures to maintain order amid rising dissatisfaction among civil society, business and the military.

Economic interventions

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) has been battling currency instability since the reintroduction of the Zimbabwean dollar in February 2019. Over the past 19 months it has revised the monetary policy framework several times in an attempt to address the high inflation rate and limited currency reserves, often in a haphazard and unpredictable manner. To date, none of these interventions has been successful. Limited reserves of the Zimbabwean dollar and low confidence in it, alongside the persistent demand for foreign currency by both business and consumers continue to fuel the growth of the parallel market, resulting in the ongoing erosion of the value of the local currency.

As the country has slid further into hyperinflation, the government in June and July made several far-reaching economic interventions:

New foreign exchange trading system: On 23 June, the RBZ introduced a foreign exchange auction system (FEAS), replacing the fixed exchange rate system adopted in March. The exchange rate is determined by the average of bids for hard currency made once a week. This has seen the official exchange rate settle at ZWL 57 to USD 1, higher than the fixed exchange rate of ZWL 25 to USD 1.

Ban on mobile money payments: On 26 June, the government banned all mobile phone-based payments, citing the need to address “economic sabotage”. It accused the largest mobile money platform, EcoCash, of distorting the official exchange rate by trading in US dollars. Mobile money payments account for around 84.8% of all transaction volumes in the country, according to the RBZ, following long-term cash shortages at banks.

Closure of the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (ZSE): On 30 June, the army shut down trading on the official stock exchange with immediate effect, reportedly without consultation with the country’s economic chiefs. The ban remained in place for over a month, resuming on 3 August.

Suspension of three companies from the ZSE: The government in July suspended Old Mutual Ltd, PPC and SeedCo from trading stocks, accusing them of distorting the official exchange rate. Ncube stated there was a link between the movement in prices of these three dual-listed stocks and the climbing parallel market rate of the Zimbabwean dollar (estimated at between ZWL 75 and ZWL 95 to USD 1). These companies were excluded from trading on the ZSE when it reopened on 3 August.

Growing business challenges

Ongoing revisions to monetary policy are doing little to stabilise the currency, given that it can take anywhere from three months to two years to witness any impact on inflation. The adoption of the FEAS represents the fourth monetary policy shift since the local currency was reintroduced, while the RBZ has previously switched monetary policy regimes within a period of three weeks.

As well has having limited success, the frequency of these revisions is driving ongoing uncertainty for businesses across all sectors. Changes occur frequently around the use of foreign currency as legal tender, while the official exchange rate varies depending on the monetary policy framework. This is complicating an already difficult operating environment.

Actions taken towards companies also indicate a trend of growing hostility towards business over the past year. The recent actions against companies are not the first time the government has accused business in the country of undermining monetary policy and taken severe action. In 2019, the RBZ temporarily froze accounts belonging to four companies it accused of manipulating the exchange rate and weakening the local currency. In January, it did the same to Chinese company China Nanchang for similar reasons. It warned then that more companies would be singled out for fuelling activity in the parallel market.

Meanwhile, the closure of the stock exchange shows a disregard for investors’ property rights. This will further spook operators and exacerbate the challenges facing businesses. Assets that are tied up in the country will not be easy to shed, while the inability to trade shares publicly prevents a major source of equity finance from being raised to support business operations and growth.

Finding a scapegoat

Blaming businesses for currency instability and suspending their operations appear to go beyond the stated aim of addressing hyperinflation. It is true that dual-listed companies that externalise capital – that is, trade listed shares on the ZSE and then sell them off in hard currency on another stock exchange – can drive distortions in the exchange rate. Indeed, Old Mutual has stated it is working with the authorities to handle its listing so that it “does not continue to create the concerns raised in the recent past”.

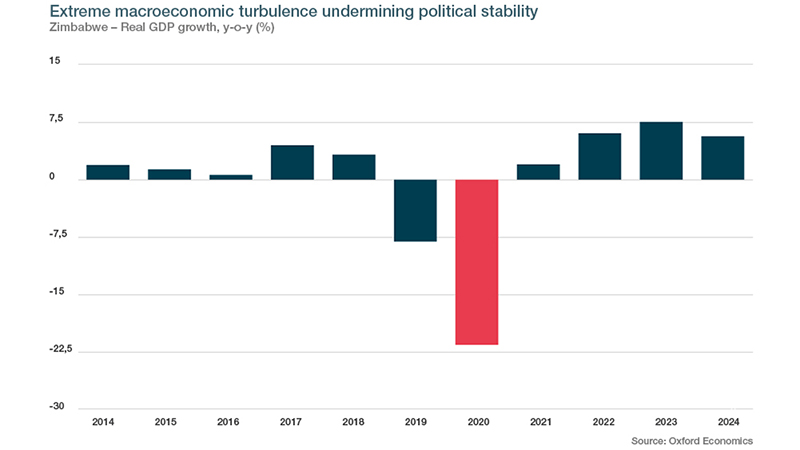

However, targeting businesses also provides a way for the government to pin ongoing economic woes on other actors. This is important as the current extreme macroeconomic turbulence has the potential to threaten political stability. Zimbabwe is facing the twin impact of an ongoing drought and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This could result in its worst economic performance in more than a decade. Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube has warned GDP could contract by 20% in real terms over 2020. The increasingly repressive stance adopted by the government in recent months reflects the growing political pressure it is facing in the wake of these challenges.

Zimbabwe – Real GDP growth, y-o-y (%)

In early May, the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF)-led government expelled members of a breakaway Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) faction – the MDC Alliance. This prompted MDC Alliance members of parliament to suspend their participation in parliament. In mid-May, an MDC MP and two youth leaders were arrested and held for several days for leading a demonstration in the capital Harare to protest the lack of government assistance for the poor during the nationwide lockdown imposed to halt the spread of COVID-19. They were reportedly beaten and tortured during detention.

Additionally, the introduction in mid-July of tighter measures to respond to the pandemic appear to be aimed less at limiting the spread than at containing political unrest. The government and army have warned that anyone participating in any kind of protest faces arrest for contravening social distancing measures.

Another coup?

The army’s clear dissatisfaction with the Mnangagwa administration – indicated by its intervention in the economy by closing the ZSE – and growing macroeconomic and political instability signal the potential for another military coup. There is no threat to ZANU-PF’s rule, given that the army is aligned with the party, and the opposition and civil society do not have the power to force a regime change. However, Mnangagwa’s position is clearly growing more tenuous.

At present, we do not expect Mnangagwa to be ousted in the coming months. First, he has no clear successor. Although in 2018 First Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga, a former army general and key figure in the 2017 coup that ousted longstanding president Robert Mugabe (1987-2017), reportedly harboured presidential ambitions, his support base has been weakened significantly. Second, the past two years have seen Mnangagwa increase his influence over the security forces. Meanwhile, the army and any potential replacement will be aware that another coup would be likely to prompt a more critical response from the local and international community than the one in 2017, given the precarious position in which it would place Zimbabwe’s already tarnished democracy.

Nonetheless, given the loss of confidence in his regime amid severe economic turbulence, there is a threat that Mnangagwa will not finish his term. This will drive further uncertainty for businesses. The lack of a clear successor means there is no way to anticipate the economic strategy of any new president. The installation of a new leader would also further disrupt the policymaking environment as attention turns towards consolidating political power and away from economic reform.