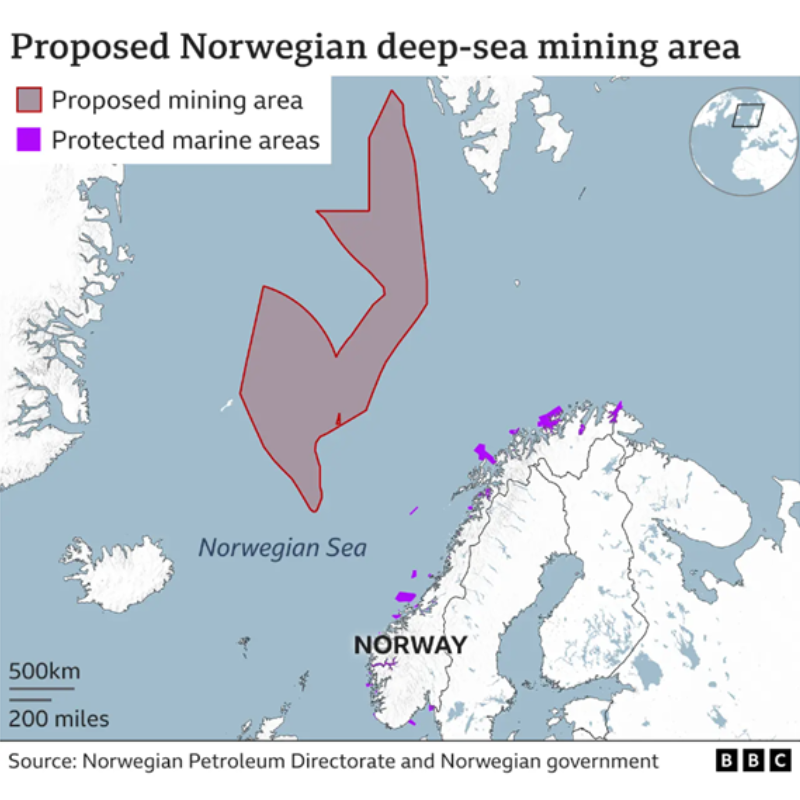

On 9 January, Norwegian legislators voted to open national waters to seabed exploration, making Norway the first government in the world to approve seabed mining. As demand for critical minerals intensifies, we expect a focus on seabed mining to intensify significantly this year, despite a high risk of associated controversy. Seabed mining carries environmental risks and could tap into or generate maritime disputes. However, it also offers huge opportunities for companies and governments alike.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-67893808

What to watch

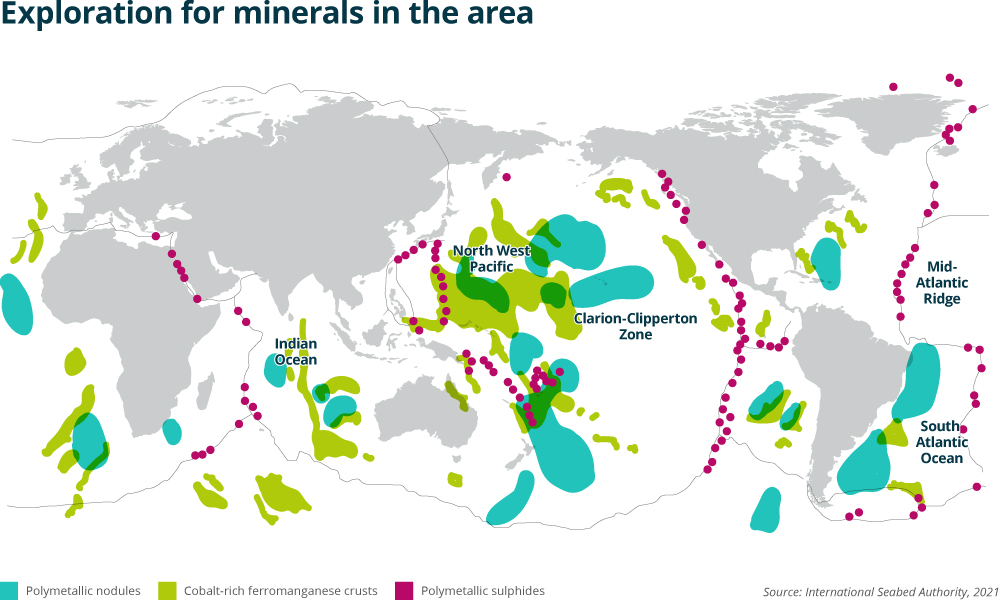

Widespread seabed exploration is not expected in 2024, and no mining is yet happening. But governments will move towards identifying and opening up water areas where seabed mining may be commercially viable, evidenced by Japan, Norway and the Cook Islands for example, and to facilitate the significant private sector investment required to extract minerals from the seabed.

Many governments will tread carefully, conscious that the ecological consequences of seabed mining are uncertain. There are also implications for a range of sectors and stakeholders including fishing communities, and navigation routes for shipping.

Seabed geopolitics

Steps forward anywhere will have implications everywhere. Seabed mining is critical to energy transition and so is ESG compliance for companies who may ultimately be involved in extracting, processing or using minerals sourced from the seabed. States, mindful of the need to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and secure energy supply, want to ensure control over access to, and trade in, minerals obtained from seabed sources.

Globally, expect continued debate, and varied regulatory progress by those states deciding to push forward. In the longer term, regulation to manage seabed mineral-linked supply chains, notably through taxation and import restrictions is likely. Progress to make seabed mining more viable also risks giving rise to questions around major geopolitical issues including unresolved maritime boundaries, and compliance or otherwise with bilateral or regional environmental regulation. Relations are likely to be tested amid the few states dominant in the space, and for mineral-rich areas beyond national jurisdiction, differing views on how exploitation should be managed will persist.

In 2024, States Parties to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) through the International Seabed Authority (ISA) will continue progress toward a mining code for what will be a novel industry. Even in the absence of a code, an earlier decision by Nauru to trigger a legal provision may force the ISA to consider a submission (with Nauru as sponsoring state) of a plan of work. Nauru is among several small island states whose seabed mineral wealth gives them greater voice in this forum than they may have elsewhere. The balance of power between states and the mining companies wanting to operate in their waters is a potential flashpoint in coming years.

How the Nauru-sponsored application would be processed – absent internal processes to respond – is likely to generate debate among the ISA’s 169 members (168 member states and the EU) and take time to progress. It will be closely watched by key players both within, and outside of the UNCLOS system. Notable among these is the US, where recent moves include a direction from the House Armed Services Committee to the Department of Defense to submit an assessment of the domestic processing of seafloor polymetallic nodules. Such action underscores the links between supply chain and national security considerations across many states.

Nauru in 2021 notified the ISA of its intention to apply for approval of a plan of work for exploitation in the international seabed area in two years. This procedure allows a State Party to request that the ISA adopt the necessary rules and regulations for seabed mineral exploitation within a two-year time frame. Following the expiry of the two-year time frame in 2023, an application in the absence of finalised rules and procedures is possible, although the commercial entity Nauru Ocean Resources Inc has indicated a preference for waiting until such rules and procedures are in place.

First mover risks and opportunities

Other states will likely take similar steps to Norway, creating conditions more conducive for business to make the significant investments needed to operate in this emerging space. This will benefit those companies already in the space and tip the balance for several waiting on the sidelines. While being mindful of the risks, those companies that invest early will be best placed to step in should other countries decide to open up their seabed, or act as a sponsoring state for mining on the international seabed in the coming years. There being elatively few operators ensures a clear first-mover advantage.

Businesses will have to maintain awareness of incoming regulation, and the implications in different markets for any move made into seabed mining space where states positions diverge. Continued scrutiny by international and national environmental groups is expected. Targeting of vessels far offshore will remain within the capacity of a few such groups, notably Greenpeace. Greenpeace activists targeted seabed mining exploration activity by boarding a research vessel in the Clarion Clipperton Zone in November 2023.

Whether considering operating in or accessing minerals derived from seabed mining as part of their value chain, companies will need to embrace stakeholder engagement. The associated risks will need to be proactively managed in a holistic and data-driven way, drawing on technology to facilitate monitoring and reactivity.

We are supporting clients by helping to ensure that their approaches to risk incorporate ESG materiality assessment exercises, scenario-forecasting, regulatory and risk monitoring, and investment due diligence, at a minimum.

Awareness of the relative value and risk associated with the emerging industry is key, given the shifts to be expected nationally and internationally in the years ahead.