Border closures and the grounding of aircraft because of COVID-19 have posed a significant operational challenge for companies. We assess the outlook for operational disruption to business associated with COVID-19-linked restrictions on movement by air, both within and between states.

- Governments are prioritising lifting internal restrictions over opening for international travel, and in some countries border restrictions will be among the final measures to be lifted.

- Most border reopening will take place within countries and regions at first, partly driven by economic imperatives and the regional integration of markets.

- The reopenings will be piecemeal and businesses will have to grapple with a complex and continuously changing patchwork of restrictions, hampering travel planning for the remainder of the year at least.

- Restrictions that have been lifted are likely to be re-imposed at very short notice in the event of renewed spikes in infection rates, compounding operational challenges.

Hard landing

With the spread of COVID-19, countries worldwide from mid-March closed their borders and introduced entry restrictions on almost all but essential travel. Those countries that did not impose significant restrictions at their borders have seen arrivals fall anyway as international airlines grounded fleets and demand plummeted.

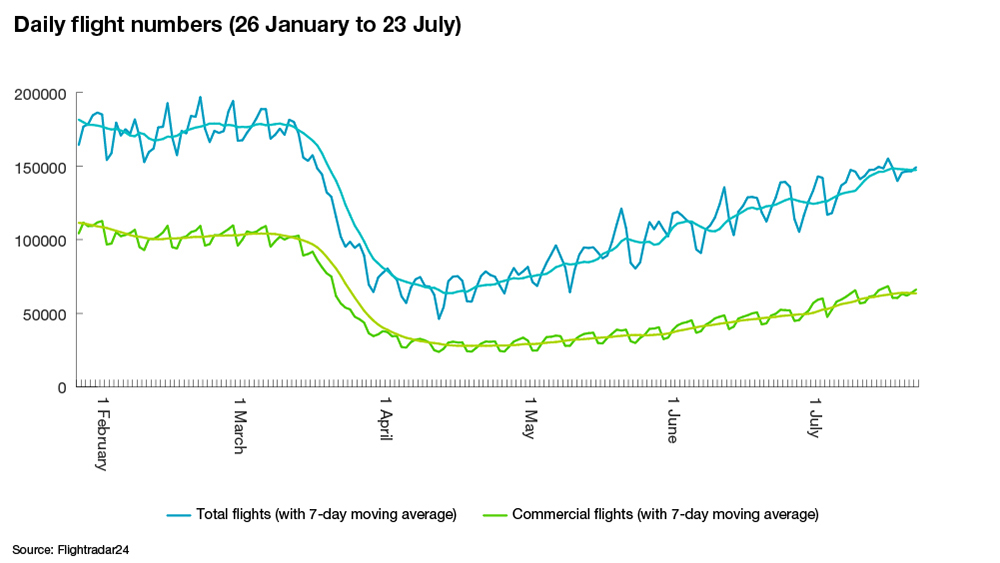

Courtesy of Flightradar24.com

Since April, there has been a modest recovery in the number of international journeys. Surging and urgent demand for personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical supplies provided some relief for struggling airlines that repurposed cabins to transport more freight. Domestic flights have also held up more than international ones, given more limited constraints on movement within countries’ borders.

Chocks away

Although “non-essential” travellers are starting to plan overseas trips or to take to the skies again, the recovery will be slow, uneven, and possibly subject to sudden reversals.

Countries have so far mostly prioritised loosening social distancing measures and lockdowns within their territories over opening up their international borders. There is little point loosening restrictions to travellers if they are then subject to stringent social distancing measures and stay-at-home orders upon arrival at their destination.

Many countries that have so far lifted or have not imposed total bans on non-essential travel are demanding that passengers quarantine on arrival for 14 days. A resumption of normal international travel under these conditions is near impossible.

Forever blowing bubbles

As an alternative to mandatory quarantines, states are starting to consider the phased reopening of borders for individuals from selected countries. Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia on 15 May opened the first full “travel bubble” or “bridge”, allowing citizens and permanent residents of the three Baltic states to move freely within and between them.

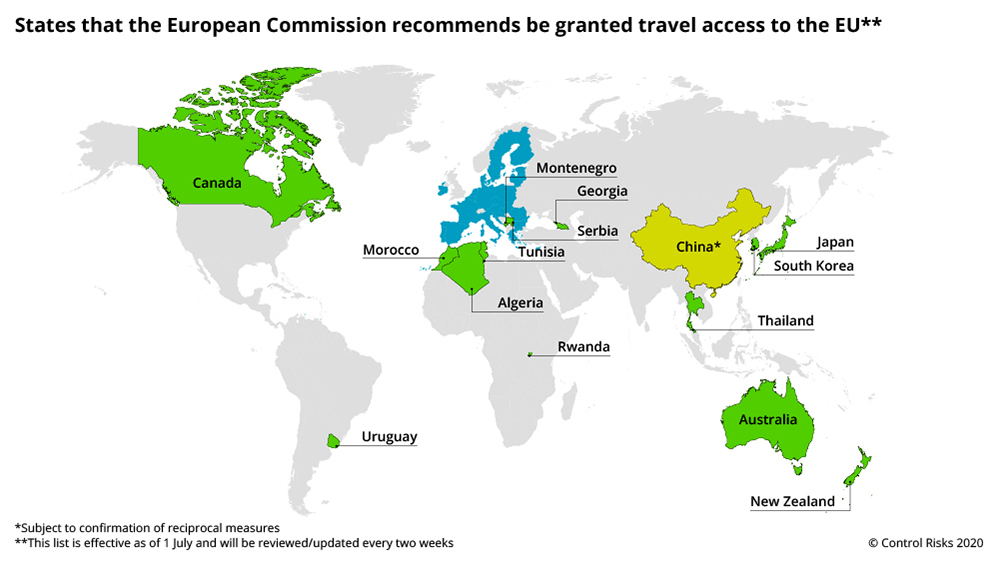

Similar measures have been brought in elsewhere in Europe. EU member states began opening up to some of their neighbours from 15 June, reinstating a degree of free movement within the single market. The bloc on 30 June published a non-binding recommendation that states allow travel from a list of countries deemed “safe” and from which travel was permitted from 1 July (though individual European governments have the right to decide how to implement the list).

A number of other travel bubbles have been mooted and remain under discussion, including several across Asia Pacific. In late April, Australia and New Zealand announced plans for a “Trans-Tasman alliance”, though this is yet to be finalised. Thailand is reportedly considering “business-travel bubbles” with Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Japan, and some Chinese provinces .

More bubbles and bridges are likely to form in the coming weeks and months. Membership will depend primarily on the spread of the virus in prospective member states, as well as the perceived capability of their governments to suppress it. Those countries that have flattened the curve of infections are unlikely to open their borders to others where cases continue to rise exponentially. Those that have the virus under control but where it is still in general circulation are unlikely to be granted unrestricted access to others where it has been almost eliminated. Those with low levels of testing and where the true spread of the virus is unclear are also more likely to be overlooked and excluded.

Economic imperatives will underpin decisions on border reopening. If there is no strong economic need to open borders between two states, then a reopening of these borders is more likely to be delayed. On the other hand, countries that rely heavily on industries and sectors that require travel (such as tourism) may look to restore movement before others, possibly taking unilateral measures to reopen before securing access to other states. Poorer states that fail to suppress infection rates may unilaterally open their borders but are likely to face the longest wait for reciprocal measures from countries other than their immediate neighbours in similar situations.

Over time, “bridges” will increasingly form over large distances. The countries for which access to the EU has been permitted include both near neighbours as well as distant states that have had relative success in suppressing COVID-19. Notably, the US has been excluded.

Geopolitical and diplomatic factors will also shape the reopening. Many countries that open their borders to others will expect reciprocal treatment. France has explicitly stated that it will reciprocate if any European country imposes a quarantine on its travellers. The EU is ready to include China on its “safe” list if Beijing offers similar treatment to European visitors. Some governments may use restrictions or the lack thereof as leverage in other unrelated negotiations or disputes. Since 31 January, the US has prohibited travel from China, despite the relative containment of the virus there, indicating that some restrictions might prove to be “sticky” for geopolitical reasons.

Reopenings could be reversed

Just as bubbles may expand to incorporate new members over time or as lists of “safe” countries grow, they can also burst or shrink as states reimpose restrictions in the event of a spike in infection rates. Europe’s list of approved countries is being reviewed every two weeks, presumably allowing access from certain countries to be revoked at short notice. After being included on the EU’s “safe” list, Serbia and Montenegro were removed at the first review. Such reversals could force trip cancellations or leave travellers stranded away from home.

The reopening of international borders will not be uniform. Other restrictions may remain in place and will vary from country to country. “Fast lanes” are one such example: these allow for travel but require passengers to test negative for COVID-19 on departure or arrival, stick to pre-identified itineraries and download the host country’s contact tracing telephone app. China has established “fast lanes” for business travel between some of its provinces and Singapore and South Korea.

Keeping it local

Although states have imposed fewer internal travel restrictions than external ones, many have limited some movement across provincial or regional borders in recent months. The varying pace of domestic reopening will add another layer of complexity to travel planning in the next few months. Where domestic restrictions are in force, bubbles and corridors will open for many of the same reasons as at the international level, minus the geopolitical and diplomatic concerns. Having all brought COVID-19 case numbers to near zero, Canada’s four easternmost provinces on 3 July opened the so-called “Atlantic bubble” to allow quarantine-free travel between them.

As at the international level, the lifting of domestic restrictions will be subject to reversal, especially as states move from applying nationwide measures to more localised ones to snuff out new outbreaks.

Longer-term outlook

The long-term outlook for the travel and aviation sectors is uncertain, not least given the significant financial hit they have already taken. IATA in June forecast that airlines will post losses of USD 84.3bn in 2020 (compared with USD 30bn in losses during the 2008-09 financial crisis). Several airlines have already filed for various forms of bankruptcy. Unprofitable routes may ultimately be scrapped entirely. A global recession will act as a drag on passenger demand throughout the coming year.

Demand is likely to take longer to rebound than the global economy. The pandemic has changed public and even business sentiment towards travel. With companies coping without travel while the most stringent of border restrictions have been in place, many are questioning the need to return to the skies at a time when costs are coming under greater scrutiny.

However, teleconferencing will not replace business travel entirely. In some sectors, moving staff internationally or between project sites domestically will remain essential to ensuring business continuity. This is likely to apply to a range of industries in sectors as diverse as oil and gas, manufacturing, and mining. Meanwhile, generating and maintaining relationships between businesses will not shift online entirely, with salespeople particularly likely to lead the way in resuming travel to engage clients in person.