In this article we explore how government responses to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic are evolving in sub-Saharan Africa, and what this means for business.

- Governments across the continent are beginning to shift responsibility for public health on to companies and individuals as they seek to restart their economies after months of disruption.

- A lack of regional coordination and often abrupt changes to reopening plans will continue to complicate travel and supply chain management in the region and sustain congestion at border trading posts.

- Meanwhile, localised lockdowns can be imposed with little or no warning, and will sustain operational challenges in some countries.

- Businesses will face a greater compliance burden in the coming months as governments increasingly introduce regulations mandating the provision of additional health and screening measures at workplaces.

Lasting caution

Most African governments responded swiftly to the pandemic, sealing their borders and implementing social distancing measures from March despite in some cases having recorded no or very few cases of COVID-19. They also implemented some of the harshest measures globally. Regional giant South Africa stopped almost all economic activity as it sought to “flatten the curve” while it readied its healthcare sector. Meanwhile, a large number of countries banned inter-regional travel, imposed curfews, closed informal markets and schools, and shut down their services sectors.

From May, governments across the region began to lift measures – but slowly. Initial easings came in response to socioeconomic pressures wrought by the pandemic and resultant restrictions. Many households, particularly those reliant on informal labour and therefore lacking any form of safety net, struggled to cope. In some countries – notably South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya and Côte d’Ivoire – this pressure resulted in outbreaks of civil unrest, including protests against restrictions and security incidents such as looting of food stores.

However, the generally slow pace of easing showed that governments were initially not willing to accept the increased public health risks entailed by restarting the economy, allowing domestic freedom of movement and reopening international borders. This was evidenced by ongoing tensions between civil society and government over the reopening of schools, particularly in South Africa, Kenya and Mozambique, and ongoing delays to the reintroduction of international flights, observed across West Africa.

It even affected trade. In May, Tanzanian President John Magufuli’s apparent refusal to acknowledge the seriousness of the pandemic and implement health and screening measures at trading posts saw Kenya and Zambia close their borders for a few days to road freight to prevent the importing of cases, despite the drastic impact on the movement of freight – particularly for landlocked Zambia.

Gradual shift in focus

Our ongoing monitoring of government responses showed a growing acceptance of increased risks to public health from the end of July, with some countries reopening their borders to commercial traffic and others allowing the hospitality sector to resume activities and permitting domestic travel. The pandemic’s hitherto relatively limited impact on the region – which has seen a limited number of confirmed cases, a generally low mortality rate and, in some cases, a high recovery rate – has driven a softening of government approaches.

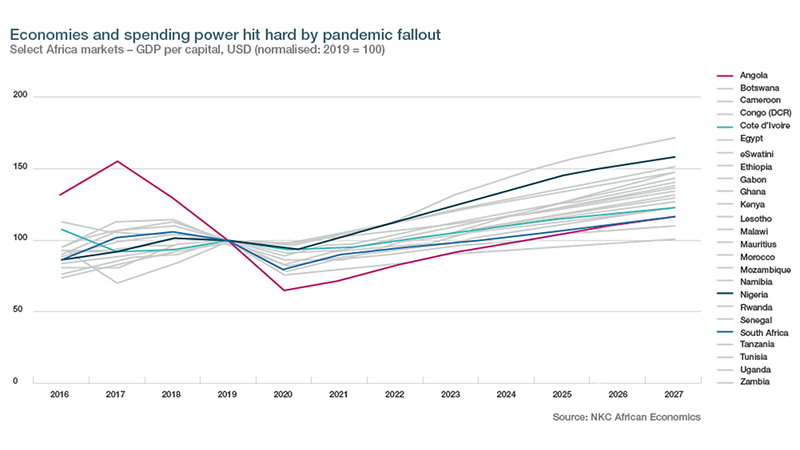

Meanwhile, regional economies have suffered a huge knock since the start of the outbreak and can no longer afford to sustain such restrictive measures. The IMF in June stated that the fallout from the pandemic would wipe out a decade of GDP per capita growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Sectors across the board – from retail to tourism, mining and construction – have been severely affected and need to be kickstarted. Although some governments have been granted debt moratoriums and have benefited from donor funding, very few – with South Africa the exception – have been able to inject the necessary liquidity into their economies. Even then, the continent’s most industrialised economy is set to record its deepest contraction in more than a decade.

Select Africa markets – GDP per capital, USD (normalised: 2019 = 100)

Instability in the region has also forced governments to prioritise other issues, particularly as COVID-19 has not had as severe a health impact initially anticipated. For example, the coup in Mali and Ivorian President Alassane Ouattara’s decision to stand for a third term have dominated the in-tray of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in recent weeks. Meanwhile, in Congo (DRC) another outbreak of the Ebola virus has taken precedence in the government’s healthcare response.

Difficult operating environment

This shift in focus will go some way towards easing operational challenges in the coming months. For example, the reopening of borders has been particularly critical for businesses and economies that rely on the regular movement of foreign labour. However, businesses will continue to face disruption from some ongoing restrictions and the lack of a coordinated regional response.

Although governments are now unlikely to reinstate nationwide lockdowns as the extensive economic disruption has become unsustainable, some favour localised lockdowns. This is where a high-risk region is placed under stricter measures and movement in and out of the area severely limited. Namibia, Botswana and Angola have used this approach to combat periodic spikes in case numbers. Namibia has placed port city Walvis Bay and most recently the capital Windhoek under lockdown. Botswana and Angola have done the same with their respective capitals, Gaborone and Luanda. In Kenya, some county governments in and around Nairobi have requested that limits on inter-regional movement be reinstated after a ban was lifted in June. Uganda last month warned residents the capital Kampala could be locked down in the coming weeks.

These changes have often come with little advance warning, having typically been implemented within a 24-hour window and with the proposed date of lifting unclear or subject to change. Although such lockdowns will not prevent business-related travel, movement will then require permits, adding further layers of bureaucracy for affected operators.

Some governments will likely continue to use this approach. It provides a useful way to reduce movement without the extensive disruption caused by nationwide lockdowns, and helps to limit the spread of the virus from urban to rural areas, where it is more difficult to report and treat. However, we expect this strategy to continue to be favoured largely by countries with small populations and capable security forces, given the policing of internal borders that it requires.

Limited regional coordination complicating resumption

The limited regional cooperation witnessed during the pandemic will also continue to drive operational challenges. Only ECOWAS has attempted to align its response regarding the reopening of borders, introducing a two-phase plan. However, this has had limited success. Member states continue to constantly adjust the scope of travel bans, while requiring time to adapt new health and screening measures. Meanwhile, limitations in terms of reciprocal access to other countries will continue to undermine the commercial viability of regional airlines. Senegal delayed the planned resumption of international flights by several weeks, as well as Nigeria. Meanwhile, in the latter the operating environment remains particularly complex, with federal states introducing measures that differ from those imposed by the national government.

Relations between Tanzania and Kenya will also remain strained. When Kenya reinstated international flights on 1 August (again after several weeks of delays), it excluded Tanzania from the list of countries permitted to enter, still concerned over its neighbour’s lax approach to the pandemic. Tanzania promptly revoked access for Kenyan travellers. We do not expect Kenya and Zambia to close their shared borders to trade again, but supply chains originating in Tanzania will remain subject to increased scrutiny and delays. Increased health and screening measures are also already causing logistical headaches, particularly in East, Central and southern Africa, where road networks have always suffered from congestion.

Burden shifting to businesses

As government responses continue to evolve over the coming months, they will increasingly seek to transfer responsibility for protecting public health on to companies and individuals. This will manifest in, for example, regulations mandating the implementation of social distancing measures, and other health and screening requirements at workplaces. In countries such as South Africa and Angola, lack of adherence to such regulations can result in penalties, as mandated under disaster management legislation.

These policy shifts will drive new sources of operational risk in the coming months. Businesses will need to constantly monitor and adapt to government regulations to remain compliant, and avoid costs in terms of penalties and disruption to operations.