As African countries face supply chain disruption brought about by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, we consider the various food security challenges facing the continent.

- Efforts to address the drivers of existing strains on food supplies, including climate disasters and conflict, will likely be deprioritised given the need to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic.

- COVID-19 will exacerbate food insecurity across the continent amid restrictions on movement and the resultant falling incomes, fuelling popular dissatisfaction and incidents of unrest in the coming months.

- However, the combination of COVID-19 and food supply challenges will likely prompt improvements to agricultural value chains and regional trade in the coming years.

Multiple crises

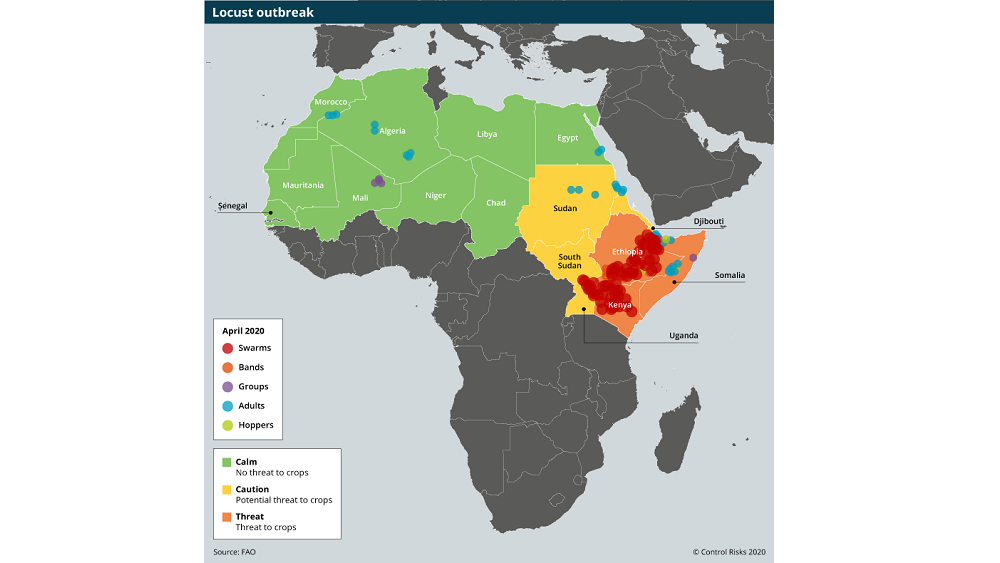

Although measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 have dominated media coverage in recent weeks, other threats to food security remain. In East Africa, the second wave of a locust swarm – estimated to be the largest in the region for at least 100 years – will have a devastating impact on harvests, and place further strain on food supplies. East Africa has also been affected by severe flooding, which has had an impact on food production and the accessibility of some regions. The World Bank in April estimated that, as a result of these crises, food production on the continent could fall by 3%-7% in 2020 unless steps are taken to prevent this.

Meanwhile, conflict-affected regions in sub-Saharan Africa – notably in the Horn of Africa and Sahel – already face critical food supply challenges given insecurity and difficulties in securing humanitarian access. This is particularly the case for regions with high numbers of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees, such as Somalia, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Mali, Burkina Faso and the Lake Chad basin. In the Sahel region, this will also coincide with the “lean season” between harvests (April-August). The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) estimates that up to 25m people in East Africa and a further 17m in West Africa will need emergency food assistance in the coming months, with more than 50m more at risk should COVID-19-induced disruption persist for several months.

Multiple causes

COVID-19 and the associated restrictions on movement are further complicating the food security situation by distracting from efforts to resolve its root causes. These include a reliance on rain-fed agriculture, limited access to quality seed and fertiliser, poor agricultural storage, weak infrastructure networks and broader inefficiency in internal food systems. Although the movement of food and other cargo continues across the continent, additional screening for COVID-19 is already causing delays to agricultural supply chains as border crossings become bottlenecks. Estimated clearance times at ports in Kenya and Nigeria have reportedly increased from days to weeks. Extended shortages have not yet been reported, but some landlocked countries such as Rwanda and Uganda have already recorded delays to supplies.

Meanwhile, the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) in April estimated that up to 70% of Africa’s workforce is employed in the informal sector. Government efforts to mitigate the negative socioeconomic impact of the pandemic through “traditional” measures such as tax breaks will therefore likely only favour wealthier segments of the population with access to formal employment.

With full or partial lockdowns implemented in many urban areas to limit the spread of COVID-19, these areas have been hit hard and will likely continue to feel the effects in the coming years. Access to daily labour and food purchases will be problematic for many urban residents as long as restrictions remain in place, potentially pushing thousands more below the poverty line. In addition, the closure of major food markets in urban areas and border towns including in Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Kenya will likely prompt an increase in food prices despite government attempts to limit price hikes through measures such as reduced value-added tax (VAT – sales tax) on essential goods.

Meanwhile, the focusing of global attention on the pandemic risks neglecting humanitarian aid considerations in areas where insecurity and conflict have decimated food systems. School meal and nutrition programmes have also been halted given school closures, exacerbating nutrition concerns among vulnerable populations. In addition, cash-strapped governments have announced the closure of some refugee and IDP camps. For example, Ethiopian authorities in April said that they would close the Hintsats refugee camp, which houses 18,000 Eritrean refugees, because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19. Although the government has committed to resettling the refugees, it is unlikely to have the capacity to do so given the need to focus on tackling COVID-19, thereby leaving thousands of people without direct government support. Supplying food for such populations is likely to become problematic and politicised, especially as countries’ own citizens also experience food shortages.

Pressures building

With patience over government restrictions wearing thin, particularly as confirmed cases of COVID-19 remain comparatively lower than in other parts of the world, governments across the region are facing rising pressure to tackle looming food supply issues. Many countries have been stockpiling vital food reserves such as maize and wheat, and media reports suggest supplies in most countries are more robust than previously, having managed through food shortages and droughts in the past decade. However, stockpiles are likely to dwindle amid rising demand for emergency food supplies, particularly if the disruption caused by the pandemic persists for several months.

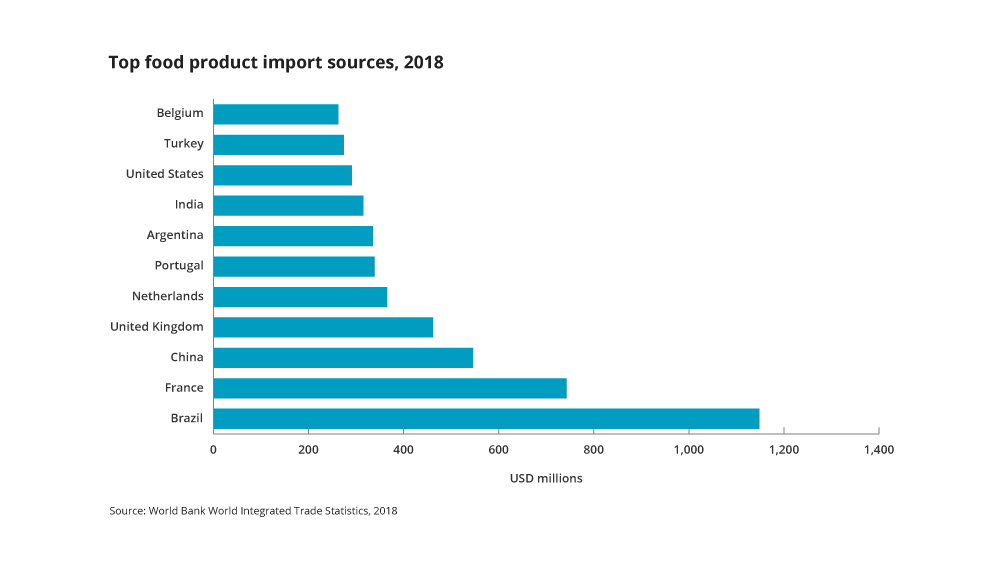

In addition, since many African governments are net food importers, this will be difficult to sustain for extended periods given other COVID-19-related budgetary pressures. Commodity-exporting countries (particularly those exporting mineral resources and oil) will find their ability to purchase additional food supplies more limited amid falling commodity prices. Countries such as South Sudan, Angola, Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea and Zambia will be particularly vulnerable. This will be further complicated as global food producers such as India, Thailand and Vietnam place temporary limits on food exports as they too seek to mitigate the threat of food insecurity at home amid concerns about the adequacy of upcoming harvests.

Moreover, African governments have limited social assistance or safety net programmes, leaving donors, charitable organisations or businesses to fill the gap for the majority of their vulnerable populations. Levels of crime and civil unrest are likely to rise as falling incomes drive economically motivated crime, as well as dissatisfaction with governments. For example, several instances of looting of shops during curfew hours have been reported in urban areas in South Africa and Kenya. Several countries across the continent – including Cameroon, Nigeria, Congo (DRC), Sierra Leone and Burkina Faso – have also seen protests by groups including taxi and motorcycle drivers, fishermen and informal traders agitating for the end of COVID-19 restrictions. It is for this reason that some African countries, including Uganda and Ghana, have lifted some restrictions in urban areas, allowing residents to resume daily food purchases and vendors to regain their incomes.

Radical redesign?

Nonetheless, the advent of several crises affecting food supplies will likely prompt a rethink of food security strategies in the coming years. Greater attention is likely to be paid to internal agricultural supply chains as nation states take steps to ensure their own food independence. Most workers across entire agricultural value chains have been designated essential, meaning that work related to food production has largely continued unhindered despite the COVID-19 pandemic. The primary problems facing producers have been the logistical and bureaucratic bottlenecks that have precipitated delays in produce reaching internal markets. Governments are working hard to reduce these. In addition, multilateral donors including the African Development Bank are channelling funding towards small and medium-sized agricultural enterprises and logistics operators. These efforts will likely have longer-term impacts beyond the current crises.

Alongside government interventions, businesses have also been forced to move their activities online, including in the food and consumer goods sectors. Across the larger cities on the continent, e-commerce platforms have added the delivery of food direct from farms and groceries from supermarkets to their services – offerings for which uptake had been limited prior to COVID-19. Bolstered by dynamic mobile service providers and expanding internet access across the continent, efforts to digitise aspects of the food supply network such as access to markets will help to eliminate blockages and inefficiencies in the coming years.

In addition, although the African Union has suspended the implementation of the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), originally due to come into effect on 1 July, to redirect resources towards the COVID-19 response, the pandemic and associated food supply challenges will also prompt a renewed effort to tackle barriers – both tariff barriers and physical barriers such as infrastructure – to regional trade. This will likely create investment opportunities as well as lower the price of food on the continent in the coming years.