The number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa exceeded 3,300 by the end of March, with cases reported in all but five countries.

Three key risk points

1/ The outbreak of COVID-19 will cause substantial economic and fiscal challenges in sub-Saharan Africa, especially in oil- and tourism-dependent economies.

2/ Enforced isolation measures and associated economic hardship are likely to fuel security challenges and political tensions, especially in countries with planned elections.

3/ Governments have moved extremely quickly to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. However, if these measures are unsuccessful, healthcare systems in many countries will swiftly become overwhelmed, raising the risk of civil unrest.

Africa in lockdown

COVID-19 was slow to reach sub-Saharan Africa. It wasn’t until 27 February that the first case was confirmed, in Nigeria, and until mid-March the virus was limited to less than a dozen countries. Governments across the region took advantage of this delay. Angola in late February began to enforce quarantine measures for all people entering the country from high-risk destinations, and on 20 March closed all its borders, despite only recording its first two confirmed cases on 21 March. Lesotho, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Comoros have closed their borders to all but their respective citizens and emergency services, despite not yet having any confirmed cases.

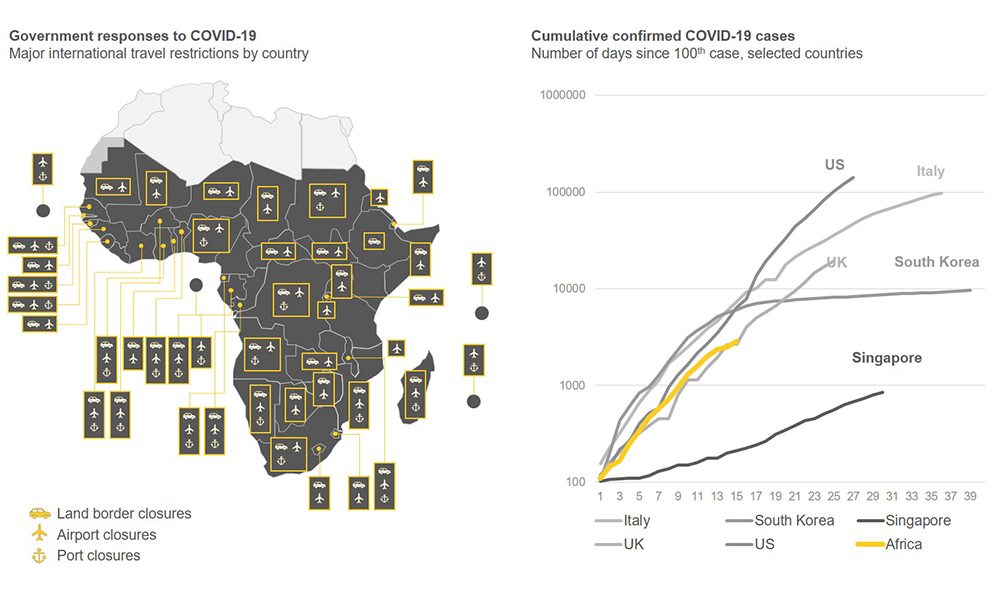

In total, 15 sub-Saharan African governments went so far as to partially or fully close their borders – closing airports, ports and in some cases land borders – before they had even confirmed a single case. As of 30 March, 46 of sub-Saharan Africa’s 49 sovereign states have imposed partial or full closures of their borders; 44 have closed schools, banned public gatherings, or put in place other social distancing measures; and 11 have declared a state of emergency. On a regional level, sub-Saharan Africa arguably responded more quickly and decisively than anywhere else in the world.

It is too early to determine how effective this government action has been. As of 31 March, there were confirmed cases in 44 countries. However, 45% of the total number of confirmed cases are in South Africa, 9% in Burkina Faso and 6% in Senegal. Only 24 countries have confirmed cases of domestic transmission, suggesting that some may have been successful in isolating imported cases quickly enough to prevent an outbreak. In many countries the number of confirmed cases remains in single digits even after one or two weeks. This is cause for optimism, with the caveat that a lack of testing or transparent reporting may be significantly distorting these numbers.

Prevention beats treatment

A number of media commentators initially argued that Africa might be shielded from the worst of COVID-19, and several maintain this stance. A young population is less vulnerable to the more severe symptoms of the virus, while low population densities and hotter climates could reduce transmission. But these factors may not provide the protection that many hope or they may be offset by other factors such as high rates of HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis in many countries. The number of cases in sub-Saharan Africa is increasing at a rate comparable to other regions at similar stages of the outbreak.

If African governments are unable to prevent outbreaks and are not protected by demographic or climatic factors, COVID-19 could spread quickly. Several countries have valuable experience of surveillance, contact tracing and community awareness campaigns, gained during recent outbreaks of COVID-19 and other diseases. The Pasteur Institute in Senegal is drawing on its experience to work with a British biotech company to develop a cheap and quick test for the virus. But even with this experience, governments will struggle to contain the virus. Social distancing guidelines are impractical in densely populated informal settlements and in economies that depend in large part on informal trading. A recent poll on COVID-19 in Nigeria found that 63% of people depend on daily earnings for subsistence.

And if COVID-19 spreads, healthcare systems in much of the region are ill-prepared. Public health spending in sub-Saharan Africa has been flat for the last two decades, at an average of 5.2% of GDP, compared with 10% globally. In various rankings measuring healthcare indicators or vulnerability to pandemics, African countries perform poorly: sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 17 of the 20 lowest ranked countries in the Healthcare Access and Quality Index; 18 of the 20 countries ranked most vulnerable in the Rand Corporation’s Infectious Disease Vulnerability Index; and 18 of the 20 countries ranked most at risk in the European Commission’s INFORM Epidemic Global Risk Index. Data shows that most African countries have fewer than 100 intensive-care beds; Nigeria may have more lawmakers and senators in Abuja than ventilators across 36 states.

Bitter economic medicine

The economic toll of the crisis is already visible, exacerbated by the cost of mitigation measures to prevent outbreaks. This year was supposed to be a recovery year for sub-Saharan Africa: the region’s GDP growth was projected at 3.5%, with bright prospects in East and West Africa in particular. South Africa would gradually recover from years of stagnation, while countries such as Angola and Namibia were due to come out of recession. Growth forecasts are now being slashed.

Africa’s oil exporters are arguably being hardest hit. Nigeria based its 2020 budget on a forecast oil price of USD 57 per barrel, and Angola on a slightly more conservative USD 55. As of 27 March, the global price for a barrel of Brent crude was less than USD 25 per barrel. Both countries now face major drops in government revenue. Africa’s tourism sector was the second fastest-growing in the world, accounting for 8.5% of the continent’s total GDP – and far more in smaller countries such as Mauritius (24.3%) – but has ground to an almost complete stop. It is too early for reliable statistics, but what data there is suggests a massive slowdown in both investment and trade. The more diversified economies of East Africa and the West African Franc CFA zone (UEMOA) are in a better place to weather the crisis, but there are no winners.

Adding to this slowdown in economic activity is the fiscal cost of government responses. Initial responses in sub-Saharan Africa have primarily involved monetary policy adjustments by central banks to shore up liquidity and freezes on spending. Some governments have announced stimulus or social welfare plans. In Madagascar, for example, President Andry Rajoelina has introduced a “social emergency plan” that includes food and cash disbursements for those unable to work due to the lockdowns imposed on Antananarivo and Toamasina.

In absolute value, none of these measures come close to the packages announced by governments across Asia or the Western world. Madagascar’s “social emergency plan” allocates just MGA 10bn (USD 2.7m) for cash disbursements, alongside a planned injection of MGA 620bn (USD 165.6m) of central bank capital into the banking system to increase liquidity. But they represent huge expenditure for governments that in many cases are already struggling with significant debt burdens. An October 2019 report by the IMF identified seven African countries as being in debt distress and another nine at high risk. There are ways of potentially funding response and stimulus packages: nearly 20 governments have requested emergency support from the IMF; African finance ministers have already called on wealthier creditors to suspend debt repayments; and the African Development Bank (AfDB) has raised USD 3bn through a “Fight COVID-19” Social Bond. Nonetheless, it is difficult to see many countries respond at the scale necessary while avoiding substantial increases in debt.

Associated security symptoms

Meanwhile, a combination of enforced isolation measures and economic hardships will trigger incidents of unrest, such as those witnessed in Liberia during the 2014-15 Ebola outbreak. On 17 March in Senegal security forces clashed with dozens of people who were defying movement restrictions to attend a traditional ceremony. A riot broke out on 23 March in Niger after authorities closed mosques and arrested a popular cleric who had defied a ban on religious ceremonies. In South Africa and Kenya there have been protests by taxi drivers angry over the impact of lockdowns on their livelihoods.

There have also been reports of mob violence against foreign nationals suspected of propagating COVID-19 in Ethiopia, Uganda and Kenya. There is a threat that engaging security forces to enforce isolation measures will allow room for Islamist or other militant groups to strengthen in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa or northern Mozambique. Meanwhile, necessary measures to contain the virus may be perceived as authoritarian attempts by governments to consolidate control, leading to a loss of faith in democratic processes. Ethiopia is said to be considering postponing its August general elections, and opposition parties – some of which were until very recently armed militant groups – would resist any delays. A further eight presidential elections are due later in 2020, including in countries where political tensions are already high, such as Burundi (20 May) and (2 July).

Inflation, spending cuts and frozen projects will disrupt the patronage flows of many regimes, especially in the petro-states of Central Africa. Because the mobile elite is smaller and more likely to visit the same places, the worst-case scenario – COVID-19 hitting at the heart of government – is no longer a remote possibility. In recent days, six ministers in Burkina Faso and the Nigerian president’s chief of staff have tested positive.

All these risks – economic, security and political – will increase the longer restrictions are in place and normal economic activity is suspended. They will also rise if the number of COVID-19 cases increases, overwhelming healthcare capacity, fueling anger and fear, and prolonging restrictions on international travel. If the rapid action taken by governments to prevent outbreaks are successful, sub-Saharan Africa may soon start to recover. For the time being, governments and companies should hope for the best and prepare for the worst.