Four key issues:

1. The fragmentation of the European Parliament and decline of the two main political groupings will complicate the appointment of senior EU figures.<

2. Filling the key posts will also require the balancing of national and EU-level concerns, and the process is likely to take several months.

3. Despite increasing their presence in the European Parliament, Eurosceptic figures are unlikely to gain any of the major EU roles.

4. Whoever occupies the top jobs, an increasing focus on environmental legislation is likely in the coming European Parliament term.

All change at the top

Former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger may never have asked the apocryphal question, “If I want to speak to Europe, who do I call?”, but the fact remains that there is no one figurehead in the EU and the bloc has multiple key players. By the end of this year, the four key roles – Commission president, Council president, Parliament president and High Representative for Foreign Affairs – are all highly likely to have new occupants and, once again, the rest of the world will need to work out where the real power lies in Europe.

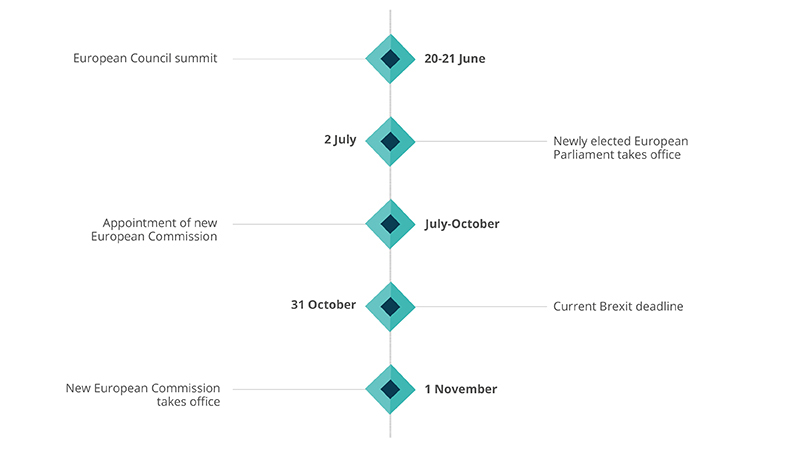

Appointing these figures is a balancing act between reflecting the results of the European elections and meeting the demands of key member states. Both the European Parliament and the European Council have veto rights over Commission selections, while each body individually selects its own president. Informal bargaining between EU leaders began the day after the results of the European elections were announced, and formal discussions continued at a meeting of EU heads of government on 20 and 21 June. The plan is for the new European Commission of 28 (27, if the UK has left) national representatives to take office in November. However, with the European elections failing to produce a single, strong political bloc and with differences emerging at member-state level, this timetable may need to be revised. It could be 2020 before all the posts are filled.

EU timeline

The role of parliament

In addition to having the ability to block any appointment (a majority must vote in favour of a nominee), the European Parliament is relevant to the process of selecting the new European Commission president by way of the so-called Spitzenkandidat process. This was brought in ahead of the previous European elections in 2014 in a bid to bring greater transparency to the process of choosing the Commission president.

Although political parties run on their own tickets within national borders for European elections, they sit in transnational groupings along ideological lines in the parliament. Under the Spitzenkandidat system, each political grouping in the European Parliament nominates a candidate for president. The position then goes to the candidate for the bloc that wins the most seats in the European Parliament. This system was used to appoint current European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker. However, the process is much more controversial on this occasion, as the largest political group – the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) – saw its vote share decline and its proposed candidate, German politician Manfred Weber, lacks executive political experience.

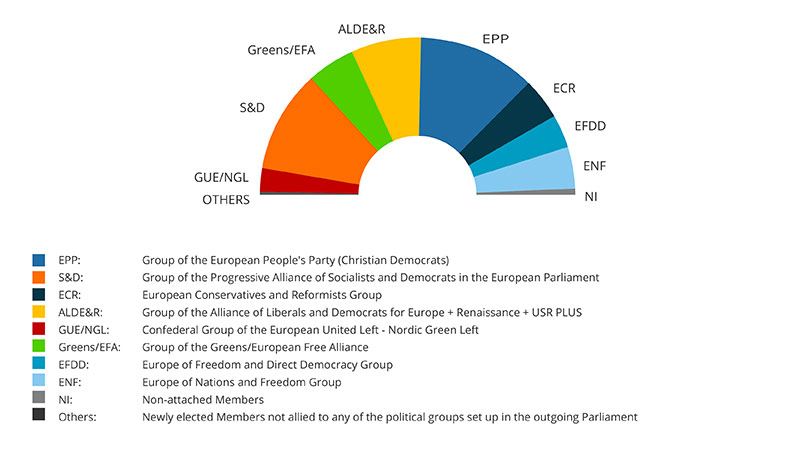

The following graphic shows the breakdown of the groups following the 2019 European elections, using the names under which they stood for elections and nominated presidential candidates – the centrist Alliance of Liberals and Democrats in Europe (ALDE) and the far-right Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF) have since changed their names to Renew Europe (RE) and Identity and Democracy (ID), respectively.

Political groups in the European Parliament

The EPP remains the dominant actor in the 2019-24 parliament, but it has seen its vote share fall since 2014. An increase in the number of Eurosceptic MEPs, combined with the dwindling support and reduced representation for the centre-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), has reinforced the trend of fragmentation in the parliament. Together, the EPP and S&D have 332 MEPs, 44 fewer than needed to form a majority. As a result, they will need to ally with either RE or the Greens, or both, to create a majority to keep the Eurosceptic influence down. However, in doing so, they may need to compromise on adhering to the Spitzenkandidat process. RE – which includes French President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance national list – has been particularly critical of Weber’s suitability for the Commission presidency and would likely vote against his confirmation and prevent him from gaining majority backing. However, for now at least, the EPP remains committed to the Spitzenkandidat process and to Weber, and they could also block an alternative candidate. As a result of these divisions the process to appoint a new Commission president is likely to take several months.

A Divided Council

Weber also has multiple critics within the European Council. Despite the Spitzenkandidat system, it is the European Council of EU heads of government that officially nominates the Commission President. It appears that a majority of council members oppose Weber – or are at best lukewarm about his prospects (including German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who officially backs him). However, if they reject him, they will need to find a candidate who can get parliamentary approval. One option could be to find an alternative, compromise EPP candidate. The most obvious choice would be Michel Barnier, the EU’s lead Brexit negotiator. He would satisfy the demand for an EPP candidate, but, as a Frenchman, could also appeal to Macron. Alternatively, the Council could push for a candidate from another grouping, such as RE’s Margrethe Vestager (currently European Competition Commissioner) and offer the EPP one or more of the other major roles, most likely Council and/or Parliament president.

Eurosceptic surge overblown

Headlines across Europe in the run-up to European elections often indicated that the European parliament was about to be overrun by Eurosceptic parties. This was borne out to some extent, with parties fitting this description winning the most seats in Italy, France, the UK and Hungary. However, overall gains by such parties in the European Parliament were relatively modest. In addition, despite the efforts of prominent figures like Italian deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini to form a solid bloc of nationalist parties, this will have a limited impact on both the selection of candidates for president and on longer-term policymaking. Salvini and the leader of the far-right French National Rally (RN) Marine Le Pen have trumpeted the creation of ID. However, diverging policy stances on issues including relations with Russia, migration and budgetary discipline, will make cohesion difficult. In addition, the decision of Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage not to join ID confirms divisions between the Eurosceptics and demonstrates that they will struggle to form a cohesive bloc to try to disrupt policymaking.

In terms of the process for replacing EU figures, the Eurosceptic parties are likely to have a limited impact. They might be instrumental in blocking a more liberal candidate if the EPP also opposes an appointment, but they will not be able to prevent a candidate with the support from the centrist blocs from taking office. Salvini has argued that, as his League has among the largest numbers of seats of any party in the European Parliament, a candidate of his choosing should be well placed for a major position in the EU. He has said that he wants Italy’s commissioner to hold the trade, competition or agriculture brief. However, this is very unlikely to transpire. Even ignoring the fact that domestic pressures in Italy could prevent a League representative being nominated as Italy’s commissioner, a Eurosceptic candidate would be very unlikely to be approved by the European Parliament for any of these roles.

Green priorities

One wild card option for a major position that could gain widespread support would be a Green candidate. Green parties performed above expectations in several member states and the mood in Brussels is very much that the EU will need to focus on tackling climate change in the next five years. Even without a key role for a Green politician, the increasing presence of Green representatives is likely to reinforce the European Parliament’s focus on environmental legislation in the coming term. While measures like more ambitious carbon emission reductions will continue to divide opinion at Council level, they are likely to have an easier ride in the parliament. Traditional political parties in those member states where Green parties did well are already beginning to indicate that they will respond to this success with increasingly Green policies, and this is likely to aid the passage of environmental policies at EU-level. However, before policy making can begin in earnest, those key EU positions will need to be filled.

Part of the Big Picture Series, taken from Seerist.