Infrastructure and geopolitics are inextricably linked – from the development of public-private partnerships (PPPs) in response to inflation and high interest rates caused by geopolitical turbulence in the 1970s to Donald Trump rolling back Biden-era momentum for renewables in the first weeks of his second term.

With geopolitical flashpoints in Ukraine and the Middle East in constant evolution and a US administration rewriting the foreign policy playbook, investors must remain vigilant. This article looks at four geopolitical shifts that are shaping infrastructure investment.

Energy transition meets energy security

Geopolitical dynamics, including national security expansion, the Ukraine conflict, instability in the Middle East and intensifying US-China tensions, have prompted decisionmakers to reevaluate their critical energy infrastructure.

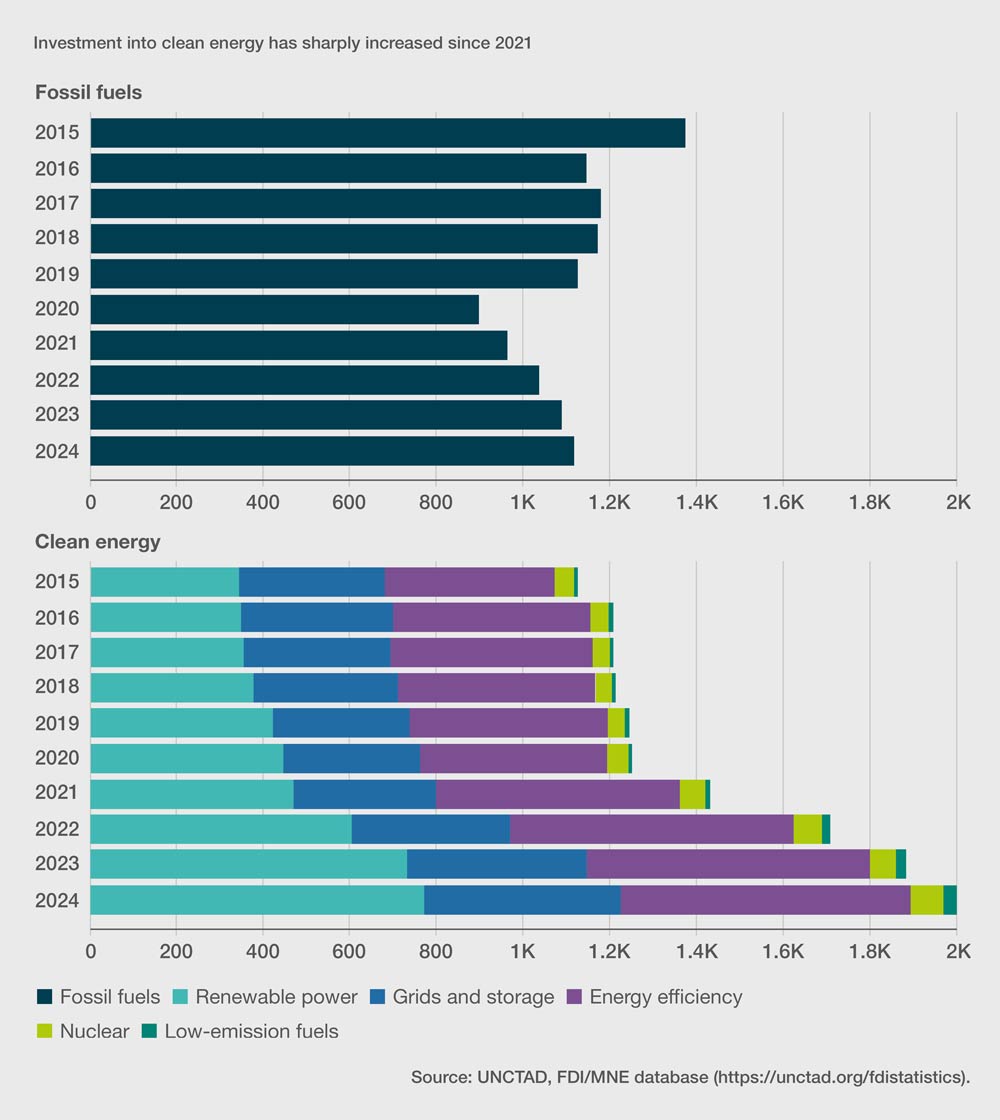

Globally, governments have shifted to viewing the energy transition as interconnected with energy security. As a result, they have sought to advance domestic renewable energy capacity, expand power grids and diversify supply chains. Reflecting this trend, global energy infrastructure investment is set to exceed USD 3trn for the first time in 2024, with USD 2trn going to clean energy technologies and related infrastructure. Access to electricity also underpins the integration of renewable energy technologies – including electric vehicles (EVs), solar panels, wind turbines, battery storage and heat pumps – into wider energy networks. Electricity grids have benefitted from the largest percent increase in investment in recent years (reaching USD 85bn); however, even with increased investment, electricity still lags well behind other key areas.

Growth in clean energy infrastructure investment remains highly concentrated among the key economies of China, the US and the EU, supported by legislation such as the EU’s REPowerEU. However, the amount of investment in clean energy is rising in India, Brazil, and parts of Southeast Asia and Africa amid new policy initiatives and improved grid infrastructure, providing key indicators of fledging growth.

Flashpoints and investment: Foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows into Europe tumbled after the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war. Over time, the war has increased support within the bloc for adopting cleaner technologies and diversifying energy supplies more broadly.

Strategic partnerships

The demand for gas fired power plants will likely increase over the next decade. Geopolitical dynamics combined with domestic climate goals will drive long-term strategic liquefied natural gas (LNG) agreements. This will facilitate investment into surrounding infrastructure, especially digital infrastructure, which is heavily reliant on access to power and cannot rely on renewable energy alone.

At present, LNG markets are highly concentrated. However, more than 250bn cubic meters per year of liquification capacity is scheduled to come online by 2030, with the US and Qatar making up 60% of this new capacity. Under the Trump administration, the US will seek to boost LNG exports, including in ease permitting for new projects, some of which were restricted under President Joe Biden’s administration due to climate considerations. In February, the US and India agreed for Delhi to increase US fossil fuel imports. (The US provided a fifth of India’s gas imports in 2024.) In recent years, several governments have signed record-breaking long-term contracts with these growing LNG players: in 2023, China, Italy and France all signed 27-year contracts with Qatar.

The Ukraine conflict has increased European countries’ interest in diversifying their LNG suppliers. Italy signed gas supply deals with Angola, Congo-Brazzaville and Algeria between April and July 2022, while schemes for West African gas pipelines crossing the Sahara that had been abandoned were suddenly revived.

Europe’s interest in diversifying gas imports away from Russia will drive interest in LNG exports from new African markets, but volumes will remain small amid competition from the US, Qatar and other dominant LNG exporters. African governments will increasingly support gas infrastructure investments for domestic consumption to meet rapidly rising energy demand and support industrialisation objectives. There will be pockets of opportunities where a cluster of industrial users and gas power plants could provide enough reliable gas demand to make a project economical – like in Angola, Nigeria, Ghana and Egypt – but will still require government support to structure bankable projects.

Geopolitical competition

Geopolitical competition has spurred new funding initiatives for infrastructure in developing countries. Many of these initiatives will likely be long term and have significant impacts in target countries.

In the past decade, China expanded the mobilisation of capital, construction assets, and technology in the interest of increasing infrastructure development within several geographic corridors between Asia and continental Europe. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has continued to evolve and is now focused on sustainability, open markets and high standards of development. This stresses how future projects will increasingly be assessed for quality, risk and impact.

The US and others have announced similar development initiatives, such as the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) and the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII). The original memorandum of understanding for IMEC included plans for pipelines to transport electricity and hydrogen to Europe and India, produced using renewable sources in the Arabian Peninsula. Saudi Arabia will benefit economically by maximising its exposure to US and Chinese-related trade corridors, though Saudi-UAE competition could challenge smooth trade flows.

Innovation drives new investments

Innovation will play a significant role in upcoming infrastructure projects. Middle Powers will actively display their geopolitical pragmatism in new energy technologies, including nuclear small modular reactors (SMRs) and green hydrogen. Brazil, Colombia, South Korea and India have all announced support for domestic green hydrogen production.

India has balanced its strategically neutral positions to garner support for its nuclear energy sector. In addition to working with Russia, New Delhi has strengthened ties with France and the US to secure supplies and technology. Türkiye has reportedly started talks with the US in an attempt to attract US companies to its nuclear energy market. South Korea is also a prominent nuclear energy country and facilitates international projects regularly, such as building the UAE’s first nuclear power plant. Seoul is also engaging Saudia Arabia and Türkiye to facilitate new nuclear projects in the fledgling nuclear energy states.

AI innovation will also drive investment into related infrastructure projects. On 21 January, the US announced a private sector investment of up to USD 500 billion to fund infrastructure for AI. Further, several major tech companies have announced plans to integrate clean energy – including nuclear energy – into hyperscale data centres that support AI systems.

Business outlook

Infrastructure is entering an expansive new phase. But as geopolitics continues to rattle markets, investors must look far ahead to manage uncertainty. Studying geopolitical scenarios should always be part of long-term planning. Companies that expect complexity will have the advantage.

Authors

You may also be interested in

Download our Investing in Infrastructure Report

Our global report provides practical advice on how to mitigate risk and increase the value of your infrastructure investments.