Four key risk points:

1. Control Risks considers a majority Labour government to be an outlier scenario. However, we view a hung parliament in which no party has a majority as the most likely outcome of the election and such a result could lead to a Labour-led coalition administration.

2. A Labour government would introduce the most significant shift in business regulation in the UK in decades, including increased workers’ rights and a higher tax burden on companies.

3. Nationalisation and expropriation risks would significantly increase under a Labour government, mainly, but not only, for utilities companies.

4. Nevertheless, in the credible scenario of Labour leading a coalition government, many of the party’s more extreme policies would be likely to be watered down or abandoned.

An election for uncertain times

Businesses operating in the UK have faced an uncertain time since the country’s vote to leave the EU in June 2016. With Brexit still unresolved, a general election on 12 December compounds and increases businesses’ concerns about operating in the UK in the coming years. Although the incumbent centre-right Conservative Party has what seems like a commanding lead in opinion polls, this does not tell the whole story and a Labour-led coalition government is a credible post-election scenario.

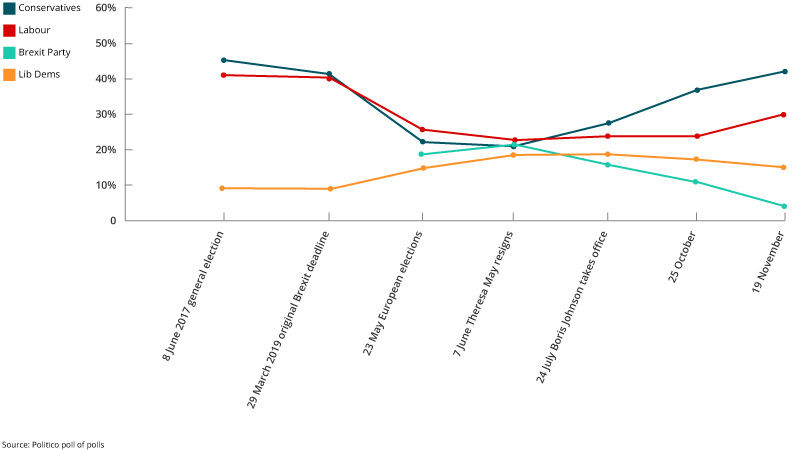

Variations in opinion polling since 2017 election

Both the Conservatives and Labour have seen their poll ratings rise since the announcement of the election in October. However, headline polls are of only limited use given the UK’s constituency-based electoral system. Parties may have overwhelming support in some areas, but almost none in others, and this variation is not reflected in national polls. The polls could be indicating that the Conservative party is increasing its support across the country, allowing it to gain the majority that eluded it in 2017. However, more credibly, the party could be attracting back Brexit Party or former UK Independence Party (UKIP) voters in areas that have always been strongly Conservative.

The election is likely to see the Conservatives take seats from Labour in the north and centre of the country but lose seats to the centrist Liberal Democrats (Lib Dems) in the south, and to the Scottish National Party (SNP) in Scotland. As a result, while there is likely to be a lot of change in terms of individual seats, the overall make-up of parliament is likely to be broadly similar, with no party having a majority. That could lead to a new minority government or see Labour gaining enough support from smaller parties to have an effective majority.

Brexit

The UK media has dubbed this the “Brexit election” and it is certainly in the Conservative Party’s interests to focus on the issue. Labour is aiming to shift the election campaign away from Brexit, on which the party has struggled to find a clear approach, and on to domestic concerns – with some success. Critics dismiss Labour’s Brexit policy as weak and the party has certainly tried to keep both remain (anti-Brexit) and leave (pro-Brexit) voters onside. The party’s manifesto provides some clarity on how it would tackle Brexit immediately after taking power, with an ambitious plan to renegotiate the withdrawal agreement within three months and hold a new referendum within six. However, the issue on which Labour – and Corbyn in particular – is most vulnerable is how the party and its leader would campaign in a referendum to choose between any new agreement and remaining in the EU.

We assess that a Labour government would prolong uncertainty over when or if the UK will leave the EU. However, it would be likely to give more clarity over the future relationship with the bloc than the Conservatives would by mid-2020, with either the UK remaining in the bloc, or leaving and staying closely aligned to EU structures.

Austerity over

Whichever party takes office, government spending is likely to increase in the next parliament. Both Labour and the Conservatives have declared the era of austerity well and truly over and pledged to boost funding of public services. However, Labour’s plans go much further in terms of cost and the increased taxation levels required to fund these promises.

Labour plans to increase public spending from the current level of around 40% of GDP to 43.3% by the 2023-24 financial year – the Conservatives plan an increase to 41.3%. Both figures are significantly higher than the pre-financial crisis levels of 37.4% of GDP in the 20 years to 2006-07 and both Labour and the Conservatives intend to fund the planned spending increase via taxation rather than borrowing. Labour also aims to increase corporation tax from 19% to 26% and to introduce a new levy on multinational companies, as well as a windfall tax on oil and gas companies. A Labour government would also increase the tax burden on more affluent individuals, with a rise in income tax rates for those earning more than GBP 80,000 (USD 103,000), higher rates of capital gains tax and a reversal of cuts to inheritance tax.

A regulatory revolution

Labour’s priority in government would be to reform the operating environment to boost workers’ rights and more closely regulate the ways in which companies operate. Labour intends to introduce significant changes to corporate governance. It would bring in a new system of oversight comprising three new commissions – on companies, finance and enforcement – to govern the private sector.

The financial services sector would be likely to be the focus of regulatory changes, including a new financial transactions tax on the trading of assets including commodities, foreign exchange and interest rate derivatives. However, Labour would also be likely to target other industries that it views as profiting at the public’s expense. For example, a Labour government would target the pharmaceutical industry in a bid to lower drug prices.

Curbing executive salaries and boosting those of the lowest paid are key tenets of Labour’s planned policies. The party intends to bring in maximum pay ratios of 20:1 for the public sector, but also for any company bidding for public contracts. Labour would move to give workers a stake in the companies where they work, by creating structures whereby 10% of shares go to employees as a right. Meanwhile, Labour would raise the national minimum wage from GBP 8.21 per hour to GBP 10.00 (the Conservatives are pledging the same and this will almost certainly come into force in the next parliament). Labour has garnered headlines in recent weeks with its plan to bring in a four-day working week. However, this is a ten-year ambition.

Nationalisation and expropriation

Another headline-grabbing element of Labour policy is its nationalisation plans. Re-nationalising the regulated monopolies of energy and water supplies, postal services and railway operators has long been in Corbyn’s sights, but the announcement on 15 November that Labour would nationalise broadband internet is a new ambition and indicates that the party might expand the scope of its nationalisation project.

When nationalising utilities companies, a Labour government’s priority would be to bring assets into public ownership and address the rate of compensation afterwards. Attempts to acquire assets based on the book value rather than market rate would be likely to face opposition from more moderate MPs and potential legal challenges. As a result, a Labour government would likely need to be pragmatic and end up paying full market value.

Housing and land reform

A Labour government plans to enact a major programme of building council and social housing but will also move to make existing housing stock more affordable. Labour would target owners of multiple properties, by increasing council tax for second homes. Longer term, the leasehold system of property ownership could feasibly be a target of a Labour government. For now, Labour will focus on increasing taxes on land ownership and making it easier for the state to acquire land.

Climate change policy

Whatever the result of the December election, the next parliament is likely to see a greater focus on environmental legislation, as all parties are pledging to do more to tackle climate change. Labour has planned a “green industrial revolution”, aiming to increase investment in environmentally friendly business and creating tens of thousands of “green apprenticeships”. Labour has also threatened to delist companies from the London Stock Exchange if they fail to take steps to tackle climate change. However, the party appears to have watered down a pledge to cut emissions to net zero by 2030 and instead is now talking of doing so “well before 2050”, while cutting the “substantial majority” of emissions before 2030. Labour’s close relationship with trade unions is ultimately likely to delay any real commitment to winding down carbon-intensive industries.

Limitations

As with any election manifesto, not all its pledges are likely to become law, even in the unlikely event that Labour wins a majority. Although some centrist Labour MPs have stood down or left the party ahead of the December election, many are likely to return and will not give a Corbyn government a free ride on his more controversial measures. Assuming a coalition is the only credible way for Corbyn to lead a government, then in all likelihood some of Labour’s policy pledges would be watered down. However, even if a Labour-led government could only implement half of its proposals, this would still represent a significant change in the UK’s operating environment.