The EU is the world’s largest open market. None of its member states nor the bloc itself would accept accusations of protectionism. Nonetheless, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated plans to give governments more room to screen foreign investment and to block on the ground of security and public order. The EU in 2019 passed legislation – due to come into force in October – to bring in a common approach for governments towards foreign investment in energy, ports and airports, and the communications and financial sectors. This was in large part driven by the pattern of foreign investment into Europe changing away from more established Western partners to emerging economies, such as China, and the growing involvement of government related entities in deals.

However, the pandemic’s impact on economies and businesses has increased the political intent behind this. The devaluation of listed companies has made them more financially attractive to investors, and bankruptcies and insolvencies have left companies looking for inward investment, especially as government support schemes are wound down and banks tighten lending. On top of these drivers, governments – many of which faced criticism for a failure to ensure the availability of medical equipment and supplies – are keen to on shore their health sectors and reassure the public that actions are being taken to manufacture equipment and supplies at home.

EU vs national initiatives

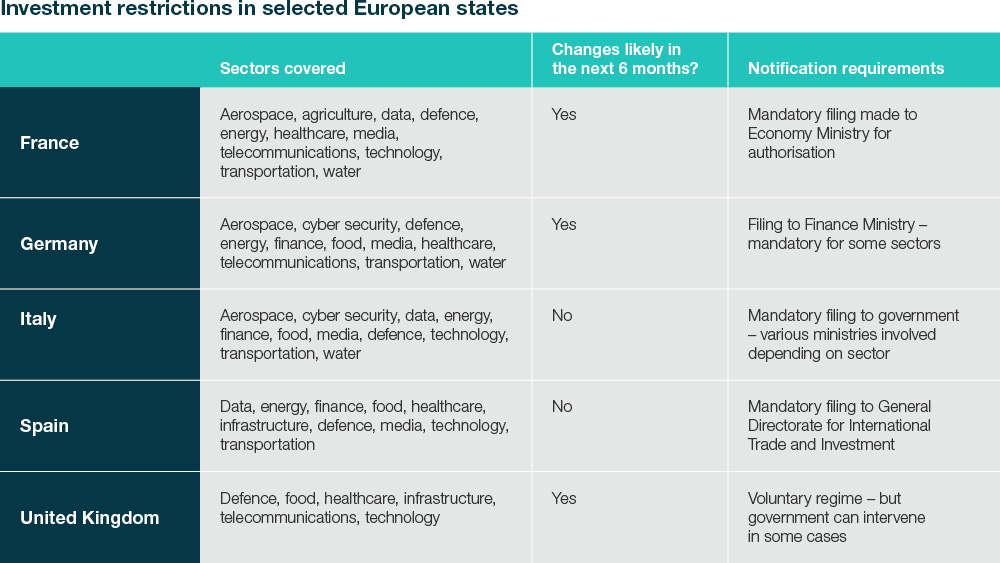

The European Commission in April urged member states to increase their vetting of foreign bids to acquire stakes in European companies, a move largely driven by a desire to avoid takeovers by Chinese entities. Mirroring these concerns, Italy in the same month announced the expansion of special powers, allowing its government to block or restrict foreign investment in strategic sectors and the German government approved draft amendments to the country’s foreign investment law, significantly broadening the scope for government intervention in planned investments. Spain, the UK and France have also brought in new measures to screen foreign investment. In some cases, like Italy and the UK, recent changes expand existing powers to intervene in takeovers of businesses in a wider variety of sectors now deemed key to national security as a direct result of the pandemic, such as healthcare and food. Although the tone and purpose of the regulation is often similar, individual governments will have different incentives and national security considerations when it comes to specific transactions.

Data and technology at the forefront

The focus on technology is evident, with governments viewing the sector as tied to national security and looking to prevent foreign governments from acquiring intellectual property and personal data. The UK government in June tabled plans for expanded powers to intervene in transactions in three areas of technological development: artificial intelligence, advanced materials and cryptographic authentication. Fifth generation (5G) mobile internet technology – and particularly the involvement of Chinese companies – is a political hot potato in Europe, with calls for policy co-ordination across Europe on how companies are selected to participate in 5G infrastructure. However, European governments are likely to pursue a range of approaches, with many already closely working with Chinese technology companies on 5G. EU-level restrictions on investment in 5G are unlikely given the diversity of opinion within the bloc, leaving governments to chart their own course.

Not just China in focus

Governments are not singling out individual countries deemed specific threats to limit the diplomatic fallout. Nevertheless, as geopolitical tensions increase between Western governments and Beijing, investment restrictions are likely to disproportionately affect Chinese companies. Bids by Chinese companies are likely to receive more attention given growing unease in many governments over Chinese state involvement in strategic industries and political pressure from Washington, DC to reduce access to new technologies and intelligence data. China is not the only power being viewed with increasing concern. With the transatlantic relationship deteriorating during US President Donald Trump’s term, Europe is keen to ensure that it has greater power to restrict US investment, particularly in areas like medical and pharmaceutical product development.

What can corporates and investors do?

Corporates and investors considering investments and acquisitions in Europe need to carefully plan their deal diligence and timelines to minimise the execution risk of a transaction. Although different countries’ regulations are clear about the conditions that should be met and when notifications need to be made to regulators, there are many political factors that will affect how screening regulation is enforced. Given this context, we think corporates and investors should be considering the following points as they approach transactions. This advice is based on our experience supporting clients engaging the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), the US agency with the most extensive precedent of any government for screening investment, and our knowledge of political risk dynamics and due diligence expectations in Europe.

1. Ensure that thorough due diligence has been conducted on the corporate structure of the parties to a transaction, their source of wealth, supply and distribution chains, and the locations of their assets and infrastructure. This can require you to go deeper than the information available to you in the data room, and to consider independently verifying the self-reported data and information. Armed with this additional diligence, investors and corporates should evaluate the extent to which these findings are likely to trigger reviews of one or more of the relevant European screening frameworks; most transactions will be multi-jurisdictional.

2. Consider whether the political dynamics around a transaction will encourage stakeholders outside the formal review process to raise security concerns about the deal. The potential for job losses and supply chain vulnerabilities could be raised by political parties, labour unions or trade bodies, either with legitimate concerns or to score political points. Investors should be mindful of important dates in the political calendars of countries affected by a transaction. Formal regulatory agencies will be key stakeholders, though corporates and investors need to flesh out a broader stakeholder map around a deal.

3. Deal teams should build alternative scenarios for responses to their deal and consider the consequences of each for execution risk and reputation management. These scenarios should consider the requirements or commitments that might be imposed by the agencies reviewing a transaction. This approach helps pre-empt regulators’ expectations, allowing proactive engaging with them; informs cost planning for possible mitigation options; and develops plans to deliver the requirements imposed by the agency. These can be informed by precedent, industry best practices and an understanding of relevant countries’ political systems.

Authors

Related article

Foreign Investment Screenings—What to Expect from European and U.S. Policies

Join us for a conversation with Pillsbury partners Nancy Fischer and Christopher Wall as they welcome Oksana Antonenko, Henry Smith and John Lash of Control Risks to discuss business implications surrounding foreign investments.