The frequency of strikes and other types of labour unrest rose in 2021 and remains elevated in 2022. Here is an outlook for labour activism over the next six months, and where it is likely to have the greatest impact.

- The COVID pandemic has driven a rise in labour activism since 2020.

- The cost-of-living crisis will continue to fuel labour activism into the remainder of 2022.

- Activism among employees will continue to disrupt travel, transport and logistics in the coming months.

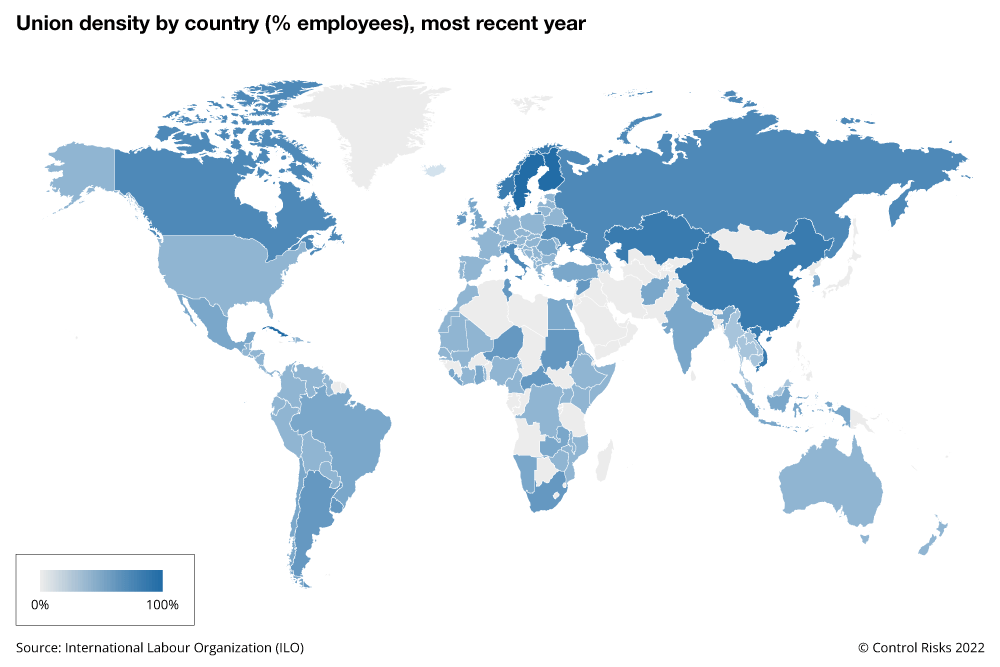

- Such activism is most likely to be elevated in countries and sectors with strong trade unions.

Pandemic impact

Control Risks’ data indicate that labour unrest increased during the pandemic. After several years of relative stability, the quarterly frequency of labour unrest incidents increased by more than 40% from Q4 2019 to Q4 2020 (after a lull during the immediate pandemic shock).

The increase in labour unrest reflected the impact of pandemic-related shutdowns on employment (especially in service sectors), work-related stress (particularly in the healthcare and education sectors), opposition to pandemic policies (such as vaccine mandates), and a broad shift in bargaining power to favour workers during the so-called “Great Reshuffle”.

Inflation now a main driver of labour unrest

Labour unrest reverted to average levels as economies reopened during 2021 but rose even more sharply towards the end of the year as inflation started to reduce real incomes. Our data indicates that the number of strikes and labour protests related to food and fuel price inflation tripled in the fourth quarter of 2021 (to around 6% of all labour activism) and has remained elevated in 2022.

Moreover, the countries with the most frequent labour unrest incidents in 2022 are not necessarily those with the highest rates of trade union membership, but rather those with the highest inflation rates. The US, for example, has recorded among the highest number of labour unrest incidents despite historically low trade union membership (around 10%) – but at a time of historically high inflation (around 8%). Germany has seen the sharpest rise in the frequency of labour unrest despite its relatively low unionisation rate (16%), corresponding to its disproportionate exposure to energy price hikes. High inflation is also a key driver of labour unrest in Peru despite declining unionisation.

Finding this article useful?

Transport and logistics highly exposed

Transport sectors are making headlines for disruptive work stoppages that are being amplified by general labour shortages in the shipping, aviation and road haulage sectors.

For example, labour action by truckers’ unions in South Korea in June caused several manufacturers and ports to suspend operations. Similarly, strikes in late June at major German ports stranded around 2% of world trade in the North Sea. In Argentina, truck drivers during the week of 27 June staged a strike and blocked major roads in Buenos Aires province. The UK in late June experienced its largest rail strike in decades. In the US, meanwhile, all eyes are on contract negotiations with dockworkers on the west coast, who handle 40% of US imports and whose contract expired on 1 July. (An eight-day strike in these ports in 2015 led to billions of dollars of losses for the US economy.)

Labour unrest – whether it involves organised unions or not – is likely to remain elevated as workers that are key to global supply chains demand pay rises to address the surging cost of living. Transport and logistics workers also have leverage due to persistent labour shortages in these sectors: the International Road Transport Union (IRTU), for example, reports driver shortages in more than 20 countries. Thousands of daily flights are being cancelled in Europe and North America because of pilot, cabin crew and ground staff shortages.

United they stand

Overall, the pandemic likely increased interest in and support for trade unions. Available data suggest that unionised workers had less exposure to pandemic-related furloughs in 2020. Indeed, the US unionisation rate rose in 2020 for the first time in years because more non-union employees were laid off (it returned to pre-pandemic levels in 2021). Unionisation rates also rose in 2020 in the UK, Canada, Ireland, Mexico, Philippines, and New Zealand, according to the ILO.

The pandemic also illuminated economic reliance on frontline, service and logistics workers – as well as these sectors’ often low wages and challenging working conditions. Anecdotal reporting and some survey data suggest that trade unions became more attractive to younger workers in advanced economies during the pandemic, and these workers have led a wave of trade union organisation. The pandemic also prompted workers to reconsider benefits and working conditions, particularly around emerging hybrid and remote work models.

However, the current global growth slowdown – potentially even a looming recession – could reverse this dynamic, tipping power back towards employers and seeing gains in wages and benefits evaporate with a prolonged period of elevated unemployment. The World Bank now expects inflation to peak in 2022, though high energy prices and supply chain disruptions are likely to keep it above the pre-COVID average in 2023.

Six-month outlook

The remaining months of 2022 could mark another peak in labour activism as workers leverage high inflation and tight labour markets. Organised labour is likely to be at the forefront of labour activism in countries and sectors where unions are traditionally strong, such as Europe and parts of Latin America, and the transport, aviation, shipping, oil and gas, and public administration sectors. However, companies should also keep an eye on sectors where labour is becoming more organised, including technology and logistics.