The transition to green energy is reducing the EU’s demand for conventional energy products. We examine how an expected decline in the EU’s energy import dependency and gains in EU energy security are likely to alter the EU’s relationships with its key suppliers.

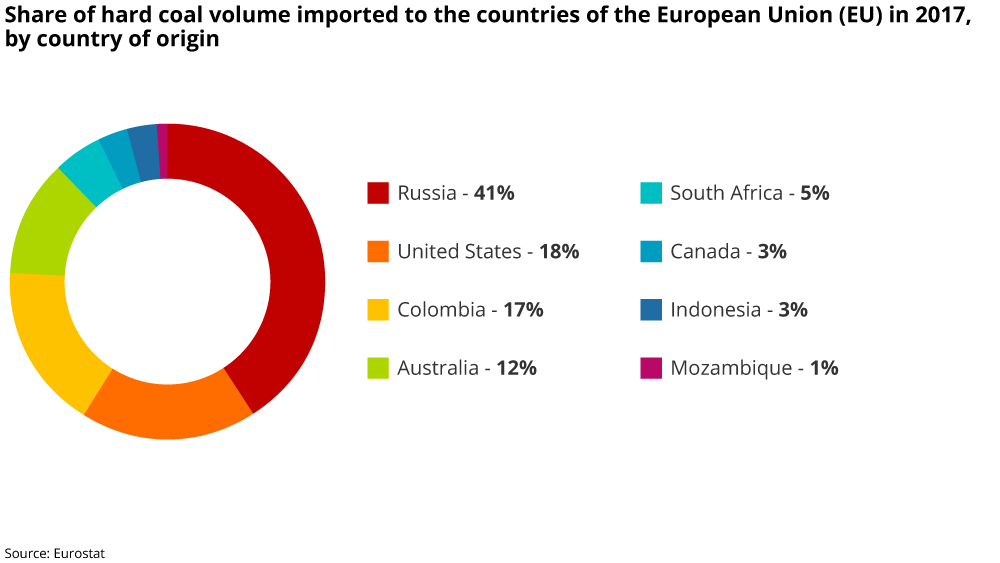

- The EU’s decarbonisation strategy – which relies on the electrification of many energy-intensive sectors – will drastically reduce oil and coal imports, while its gas imports will shift away from pipeline gas and LNG towards hydrogen and renewable methane.

- Progress in the shift towards renewables and a post-COVID green recovery strategy are likely to have moved the EU beyond the peak of its energy import dependency and to gradually strengthen the bloc’s energy security.

- The reduction over the next decade in the EU’s demand for coal, oil and eventually natural gas will have significant implications for the EU’s relations with its main energy suppliers and transit countries.

Green revolution

The EU’s Green Deal – presented by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in October 2019 – aims for the EU’s economy and society to become climate neutral by 2050. Even amid the disruption generated by the pandemic, investment in renewables across the EU has continued to increase to meet this goal. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), at 26GW the EU in 2020 is expected to generate the largest renewable electricity capacity additions after China and the US. The IEA projects that in 2021 the EU will generate 32GW of capacity additions, overtaking the US, which is forecast to remain at 29GW.

And the post-COVID outlook for the EU’s renewable energy sector looks bright. Member states have agreed to invest more than 35% of the bloc’s EUR 750bn NextGenerationEU pandemic recovery instrument into climate-related programmes, including clean energy technologies. According to the IEA’s estimates, around EUR 25bn of these recovery funds will be spent on creating new renewable electricity capacity and another EUR 3.4bn on biofuels.

EU’s peak energy import dependency

This decarbonisation strategy will not only benefit the environment but will also decrease the EU’s dependence on energy imports and strengthen its energy security.

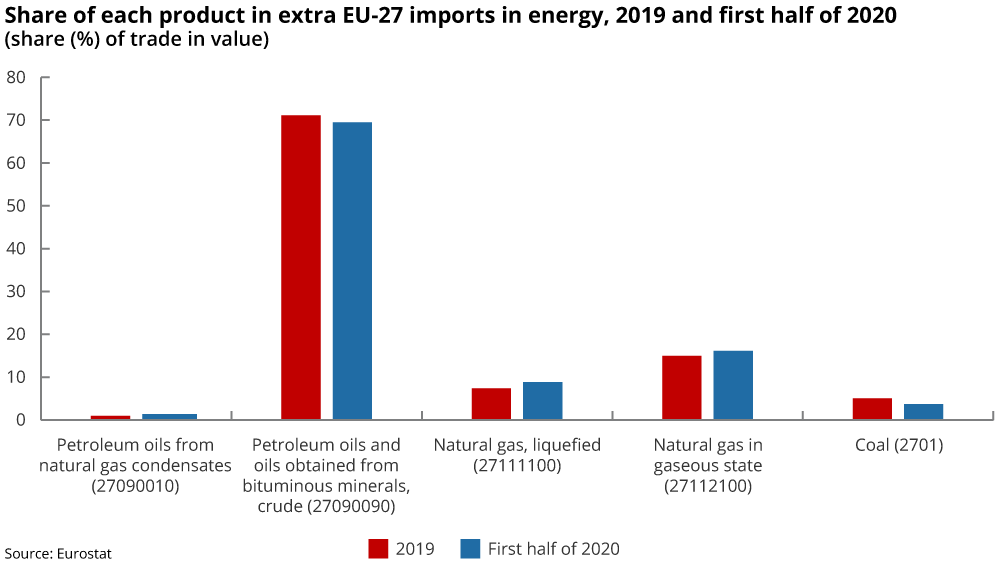

The EU became a net energy importer in 2013. By 2018 the EU’s dependency on net imports of energy products exceeded 58%. Even during the pandemic, Eurostat figures show that in the first half of 2020 the EU imported a record volume of energy products (77.9m tonnes), with crude oil and natural gas accounting for 69% and 16% of EU energy imports, respectively.

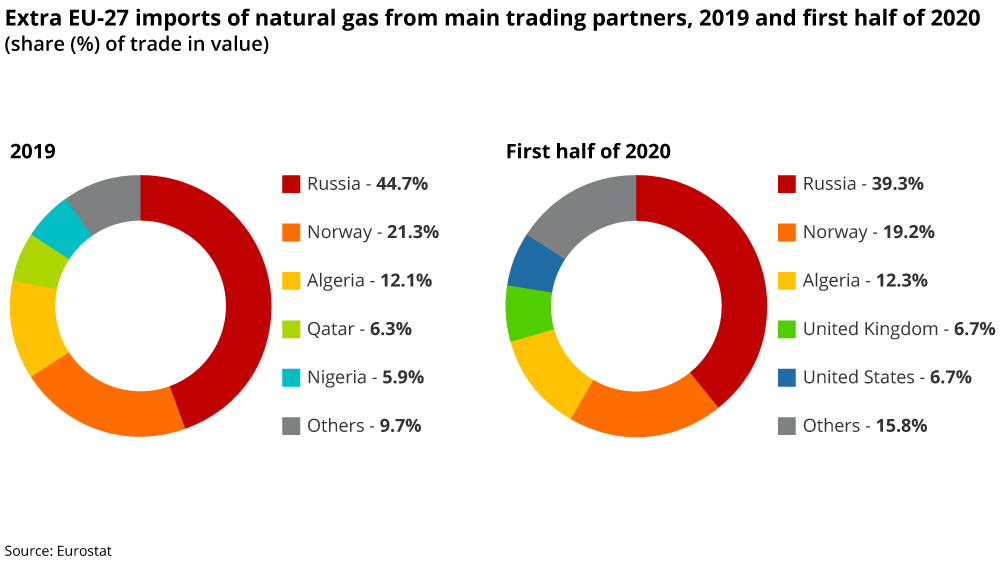

Russia has remained the dominant supplier of gas to the EU accounting for almost 40% in 2020. Russia has also continued to be the largest source of imported oil products but reduced its exports to Europe following the OPEC++ deal. While Russian production levels dropped and the price of its Urals crude soared, US shale producers rushed to claim some of Russia’s market share.

At a national level, the largest importers of energy products in absolute numbers are Germany, Italy, France, and Spain. However, demand for energy imports from these four countries is likely to drop in the next decade as these are precisely the countries that are leading the way in renewables and are likely to create a significant – and private sector-led – increase in domestic renewable power generation capacity by 2030. More than two-thirds of the EU’s COVID recovery funds for renewables are likely to be allocated to these four countries and Poland.

Energy transition will reduce demand

The energy transition will drive down the EU’s demand for coal, oil, petroleum products and conventional natural gas. The most immediate impacts will be in electricity generation, where the production of electricity from fossil fuels, especially from oil products, is slowly diminishing. Many of the existing oil-fired plants are kept only as a part of the power reserve margin, using mainly fuel oil and gas/diesel oil. Gas-fired power generation in the EU was down by 1.8% in the first quarter of 2020, compared with the same period of 2019. And in some EU member states, the decline was even greater – in Spain, Italy, and France it declined by more than 6% year-on-year.

Decarbonisation of the road transport sector will put a further dent in the EU’s conventional energy imports. According to Eurostat, road transport in 2019 accounted for 47.5% of the EU’s oil and petroleum products imports. Purchases of green vehicles (electric and hybrid) in Europe witnessed a significant increase in the first quarter of 2020, while sales fell in other segments of the automotive market. The IEA in its sustainable development scenario estimates that 57% of vehicles in the EU by 2030 would be electric vehicles (EVs), and that EVs’ share of the market would rise to 97% by 2050, which would eliminate half of the current EU oil demand.

Geopolitical outlook

The energy transition will have significant implications for the EU’s relations with its main energy suppliers and transit countries.

The reduction in EU imports of Russian oil, coal and gas will diminish economic interdependence between the EU and Russia. While this will eliminate the threat of Russia using energy as a geopolitical tool, particularly against some Central and South-East European countries that still receive more than 80% of their gas from Russia, this weakening economic interdependence will remove one of the key sources of tension in the EU’s relations with Russia.

The energy transition will reverse the growing volume of EU energy imports from the US, contributing to potential transatlantic trade frictions by further widening the trade imbalance in Europe’s favour. It will also leave some Central European states, which sought to strengthen their transatlantic bonds by investing in terminals and other infrastructure to import US LNG, with costly stranded assets on their hands.

By slashing its imports of oil and gas from the Gulf and North Africa, Europe will struggle to retain influence in the MENA region, while vulnerability among its key suppliers will increase. With some suppliers like Iraq or Libya unable to diversify their economies or to transition high value-added products – like plastics – Europe may face higher rates of irregular migration and new conflicts on its borders.

The EU’s energy transition will challenge Turkey’s ambitions of becoming a major hub for supplying gas to Europe, while diminishing the rationale for its claims and activities in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Ukraine’s role as the key gas transit route for Russian gas will be further weakened, after already being diminished by Russia’s bypass projects (Nord Stream and TurkStream pipelines). This will reduce its revenues.

With Europe and the US buying fewer resources from Russia, the Gulf and African countries, these energy producers will be even more focused on winning favour with Beijing, which is likely to continue importing conventional energy resources, while keeping a clear global leadership in renewable investments. In the growing geopolitical confrontation between China and the West, China will use its energy diplomacy increasingly with energy exporters, who find themselves squeezed by declining demand for fossil fuels, to advance its strategic interests in many parts of the world.

Outlook

While many of these outcomes will play out over the next decade and beyond, companies in Europe should be preparing to address opportunities and risks inherent in Europe’s transition away from its dependency on fossil fuels. As the EU reduces its dependency on coal, oil and eventually conventional natural gas imports, new areas of insecurity and economic crises on Europe’s periphery could emerge to impact trade, investment, and supply chains.