It has been more than two months since Russia on 10 November brokered a ceasefire to bring to an end six weeks of intensive fighting between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. We assess the outlook for the conflict in 2021.

- The ceasefire – and Armenia’s limited military resources – are likely to maintain broad peace, preventing the resumption of large-scale hostilities or further significant changes to the territorial divisions.

- However, with the ceasefire providing no resolution of the fundamental territorial dispute and several long-term issues undecided or unclear, periodic tensions and military confrontations in the conflict zone are likely.

- Meanwhile, bitter opposition to the ceasefire terms in Armenia will continue to generate domestic instability, and snap elections with a highly uncertain outcome are likely in the first three months of 2021.

- In Azerbaijan, a broad sense of victory will preserve political stability. However, the threat of a more complex security environment beyond the conflict zone is growing, as Armenian informal groups may engage in insurgent-style attacks aimed at generating disruption.

A redrawing of the map

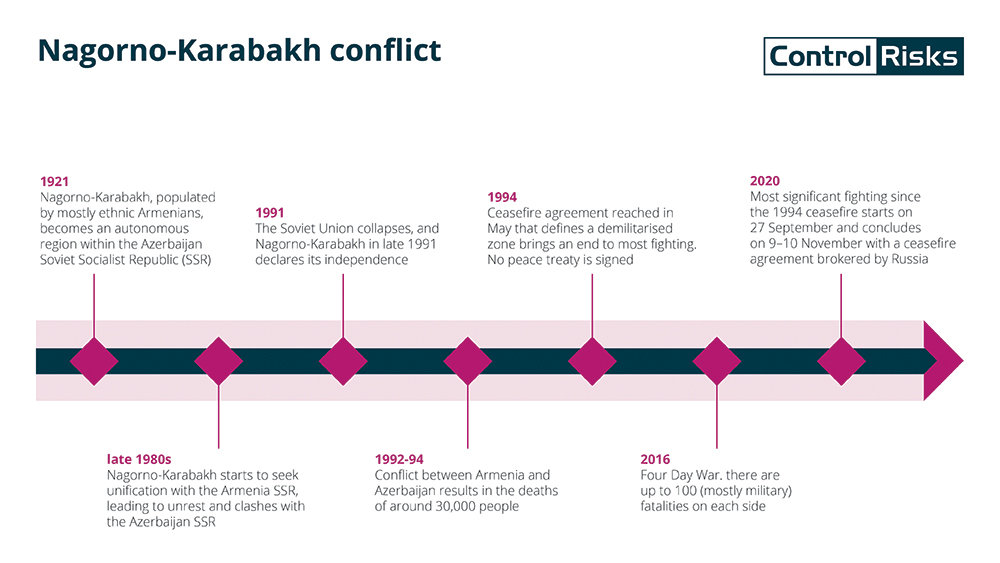

South Caucasus neighbours Armenia and Azerbaijan have remained in a state of war since 1994 over Nagorno-Karabakh, a territory that both nations consider of historical and cultural significance. A full-scale war over the territory took place between the two countries in 1988-94, at the end of which Armenia was in control of Nagorno-Karabakh, as well as seven territories adjacent to the disputed region. The international community has always recognised Nagorno-Karabakh as de jure in Azerbaijan.

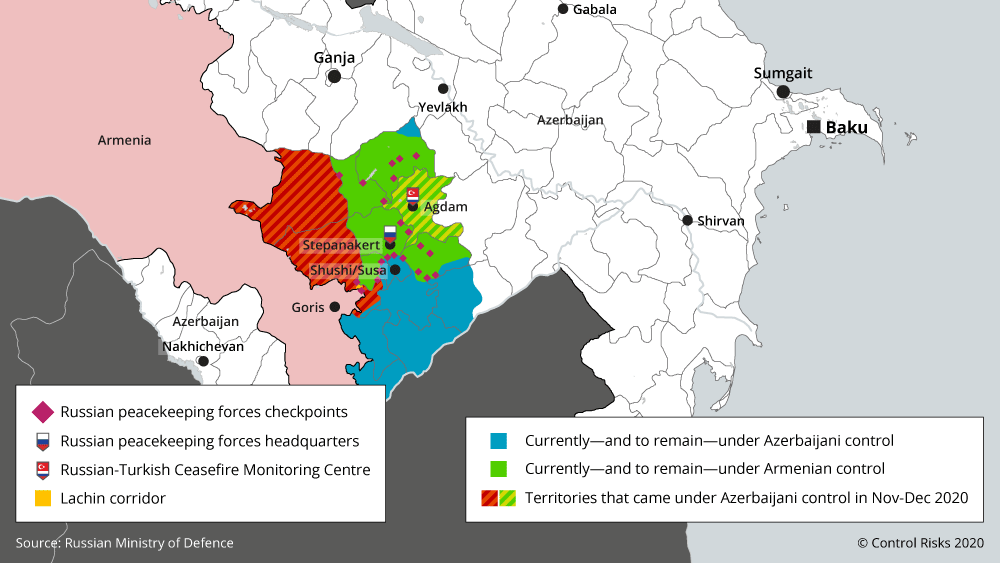

Following two decades of periodic skirmishes that saw no major change in the stagnant conflict, Azerbaijan in late September initiated an unprecedented offensive to regain control of the adjacent territories and parts of Nagorno-Karabakh itself. Neighbouring Turkey’s overt support for Azerbaijan emboldened Azerbaijan to push to make significant military advances that it previously would not have embarked on. By the time Russia brokered a ceasefire six weeks later on 9-10 November, Azerbaijan had redrawn the map, securing control of several of the adjacent territories as well as the strategic city of Shusha in Nagorno-Karabakh itself. Armenia, militarily overwhelmed and exhausted, was forced to accept these territorial losses, and to agree to hand over the three remaining adjacent territories under its control to Azerbaijan by early December.

Ceasefire to broadly hold

That handover has taken place without any major incident, and the likelihood of the re-emergence of heavy fighting is low. While Armenia feels humiliated, its armed forces are not capable of launching fresh offensives to retake control of the adjacent territories, let alone Shusha. The presence of more than 2,000 Russian peacekeepers is likely to keep broad adherence to the agreed territorial division in check, not least because Armenia remains highly economically dependent on Russia. Finally, Azerbaijan, while harbouring clear aims of taking control of all of Nagorno-Karabakh, is broadly content with the major gains it has made and will be preoccupied for much of 2021 with the expensive task of rebuilding the deserted and destroyed adjacent territories.

Many unknowns and room for tension

However, a lack of fighting is not the same as a lasting peace. The ceasefire does not resolve or settle the status of Nagorno-Karabakh, which both countries continue to claim. Whereas before this latest conflict both sides were in principle agreed that the region’s status should ultimately be decided by a referendum, an emboldened Azerbaijan no longer supports such an approach, and instead insists that it has to all intents and purposes won back the territory. This mismatch in assumptions sets back the already shaky grounds for peace talks even further.

With mutual trust between the two nations worse now than before the September-November war, the prospects of constructive dialogue are slim. The Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders met for talks in early January 2021, but this was a sign of a commitment to implementing the ceasefire rather than to pursuing a settlement. Russia, which under the ceasefire is to maintain a contingent of peacekeepers in the region for the next five years, is assuming a leading role in trying to mediate these talks, but there is now another major player at the table, Turkey. Turkey will act as Azerbaijan’s backer, rather than a neutral broker, and the prospect for tensions between Russia and Turkey is considerable.

Already in December indications of some of the more immediate thorny issues that lie ahead emerged. Ambiguity about the new borders and troop redeployments were behind both incidents. Armenian and Azerbaijani forces on 12-13 December in south-eastern Nagorno-Karabakh clashed for the first time since the ceasefire, likely owing to a lack of clarity of jurisdiction over two villages. Furthermore, since late December, considerable concern has emerged in Armenia’s southern Syunik region about the proximity of Azerbaijani forces to an Armenian road that passes along the international border between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The exact locations of Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Russian positions along this border road are yet to be confirmed.

The ceasefire also provides for the eventual creation of a land corridor between Azerbaijan and the Azeri exclave of Nakhichevan, which lies between Armenia’s western border and Turkey. This is fraught with uncertainty: Who will secure this area? Will the corridor be Azerbaijani or Armenian territory? And how will Armenians be able to cross into Armenian territory on either side? A tripartite working group representing Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia has been asking with preparing a roadmap for securing new transport links between the countries by the end of January 2021, but it is unlikely these complex issues will be easily resolved by then. Meanwhile, the issue of the return of prisoners of war is already proving highly contentious.

Security threats in conflict zone and along border to persist

As a result, security threats in the conflict zone – Nagorno-Karabakh and the adjacent territories – as well as the official Armenia-Azerbaijan border, will be high in 2021. Exchanges of fire and military confrontation between Azerbaijani, Armenian, and Russian forces stationed in the area are likely to take place periodically. Threats along the entirety of the formal Armenia-Azerbaijan border are likely to pose a new challenge. Before the recent conflict, periodic fighting took place along the northern portions of the border proper. However, in the south of Armenia, there were no such problems, since the international border with Azerbaijan was not observed because Armenia also controlled territory in Azerbaijan on the other side of that border, and the line of contact between the two sides lay further inside Azerbaijan. With Azerbaijan now in control of its side of the international border, the potential for skirmishes and confrontations that indirectly affect operators located in the vicinity has increased.

Domestic turmoil in Armenia

Meanwhile, the war and the ceasefire have unleashed major political instability inside Armenia, where the ceasefire is highly unpopular and is viewed as a humiliating defeat. A group of 16 opposition parties since the ceasefire was agreed have held regular protests to call for the resignation of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, who signed the agreement. Church leaders, former presidents and the current president have all joined those calls. Activists have called for a general strike and carried out disruptive activities to put pressure on Pashinyan to stand down.

While it is unclear what alternative to the ceasefire any of those calling for Pashinyan’s resignation advocate, momentum behind the campaign for his removal is growing. Pashinyan, who came to power in 2018 thanks to mass peaceful protests in a so-called Velvet Revolution, is standing firm against these demands, and insisting that the ceasefire was necessary to avoid the loss of control of the entire territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. While parliamentary arithmetic has allowed him to resist a vote of no confidence so far, the swelling street protests are likely to see him agree to early parliamentary elections in 2021 as a way out of the impasse.

What kind of government would emerge out of those polls is unclear. Pashinyan would almost certainly not be re-elected, but his My Step bloc remains relatively popular, and many of those leading the current protests are associated with the previous government and deeply mistrusted by the population. Complicating the picture is the presence among the political opposition of a number of mostly underground violent political groups, often described locally as “romantic revolutionaries”. While none of these would be able to launch a serious offensive against Azerbaijan to regain lost territory, their involvement in any government would likely undermine full observance of the newly drawn borders, lessening further the prospects of a lasting peace. The domestic picture in Armenia in 2021 is therefore unstable.

Stability in Azerbaijan but new security threats may be on the horizon

By contrast, the military victories in Azerbaijan have only stabilised President Ilham Aliyev and his administration. A modest but notable increase in anti-government protests since 2019 had already been largely neutralised by COVID-19 restrictions in 2020, and the buoyant public mood that has emerged from the recent war has dented the prospect of these re-emerging in any serious form in 2021.

However, those operating in Azerbaijan may encounter a more complex security environment beyond the conflict zone in 2021. As the new territorial status quo sets in and with the prospect of any progress in peace talks very low, underground or militia-style groups in Armenia may seek to exercise resistance through more insurgent-style activities. They may disrupt or sabotage Azerbaijani infrastructure through improvised explosive device attacks or more unsophisticated tactics.

Such threats have yet to transpire and at this stage remain some way off. However, Azerbaijan’s State Security Services during the conflict in October warned that Armenian special services were planning terrorist attacks in Baku and other cities amid the fighting and called on its citizens to be vigilant. Both Armenia’s and Azerbaijan’s official statements in relation to the conflict are mired in misinformation and we cannot assess the veracity of such a claim (Armenia firmly denied any such plot). However, the US embassy in Baku also in October issued a security alert, saying it had received credible reports of potential terrorist attacks and kidnaps against US citizens and foreign nationals in the city, including against hotels. It advised US citizens to exercise caution. While the US embassy did not mention the conflict in relation to the alert, it is credible – and likely – that there is such a link.

Azerbaijan’s pipeline infrastructure would be an evident target for more insurgent forms of warfare. Azerbaijan has already claimed that it has thwarted several attempted attacks on its oil and gas pipelines since late September, all of which Armenia has firmly denied and none of which has been independently verified.