Four key risk points:

1. Further well-attended rallies are likely to take place every Saturday in the run-up to the 8 September Moscow city council election.

2. These demonstrations are taking place amid a weakening in President Vladimir Putin’s popularity and an increase in the regularity of protest activity across the country, particularly focused on domestic economic and environmental issues.

3. Election-related protests are unlikely to reach the scale necessary to destabilise the central government or to generate bottom-up change in the political environment, as the cost of participating in unsanctioned rallies remains high.

4. Increasing protest activity is unlikely to prompt Putin in the next six months to unveil or accelerate plans for political arrangements following the end of his term in 2024.

Protests follow election commission decision

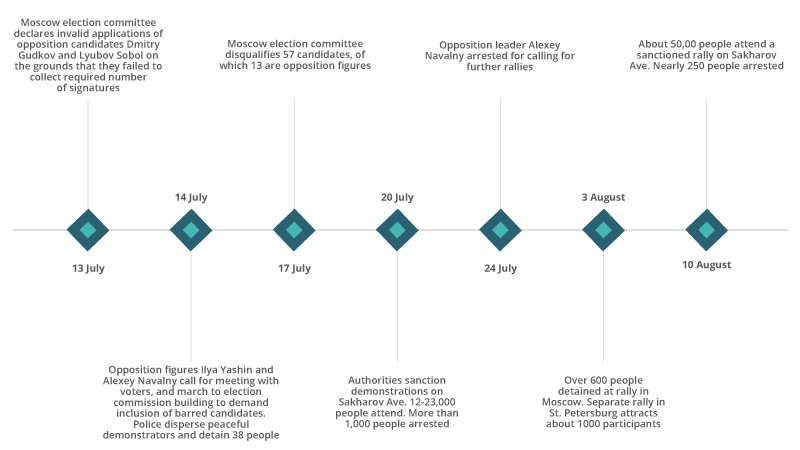

As many as 23,000 and 50,000 people protested in Moscow on 20 July and 10 August, respectively. The last time this many people took to streets was in 2011-12, when up to 50,000 people demonstrated against alleged electoral irregularities.

The recent protests were triggered by the Moscow city election commission’s refusal on 13 July to allow more than 13 opposition candidates to stand in the Moscow city council (Duma) elections scheduled for 8 September in which 45 seats are being contested. The election commission claimed that at least 10% of the signatures in support of the banned candidates were invalid.

Several popular independent opposition figures including Ilya Yashin, Lyubov Sobol, Dmitry Gudkov and Yulia Galyamina are among those barred. These candidates and their supporters allege that the signatures were rejected to increase the election chances of candidates supported by the governing United Russia party.

While the commission on 14 August allowed four lower-profile opposition candidates to register, we assess that this is a cosmetic measure, most likely designed to enable the city election commission to assert that it is not discriminating on a political basis. It remains highly unlikely to allow the registration of more popular candidates who are capable of mobilising mass support.

Timeline of protests ahead of Moscow city council elections

Crackdown

Authorities have responded with a harsh crackdown, warning that participation in unsanctioned rallies comes with a hefty penalty in the form of a jail sentence. In recent weeks, the police have blocked access to planned march routes, asked nearby businesses to close for the day, and blocked mobile internet connection in the vicinity. Police have hit peaceful protesters with batons and dragged hundreds of them into vans. Many of those detained have subsequently received short jail sentences and been fined. At least ten protesters are being investigated for inciting mass unrest, which carries a prison sentence of up to 15 years.

Meanwhile, most of the prominent opposition leaders have been jailed on short-term sentences of up to 30 days, preventing participation in the rallies. The independent Anti-Corruption Foundation led by key opposition leader Alexey Navalny is under investigation for alleged money-laundering, and Navalny was jailed in July for encouraging further rallies; he alleges he was poisoned in custody.

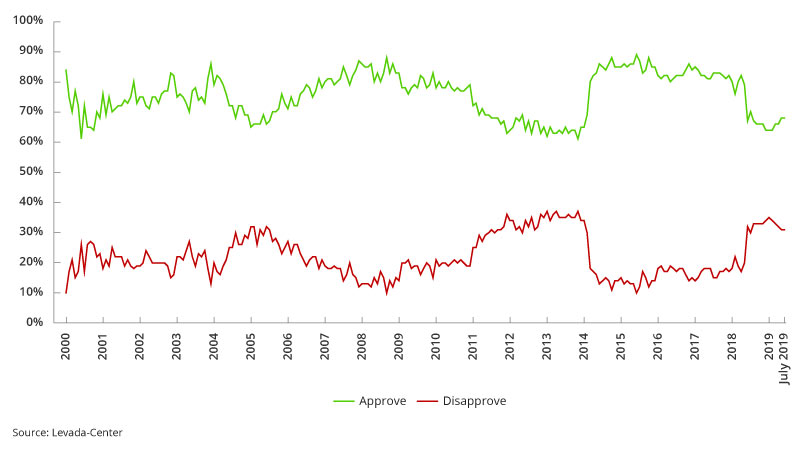

Putin’s declining popularity

At the same time, Putin’s popularity ratings have been in decline over the past year, according to polling by the Levada Center, a reputable independent polling agency. Putin was re-elected for a fourth presidential term in March 2018 with 76.6% of the vote. However, his approval rating in opinion polls since the election has fallen from 80% in March-April 2018 to 68% in July 2019. Furthermore, the number of Russians who do not want to see Putin as president after 2024 has increased by 11 points from 27% to 38% since mid-2018.

Vladimir Putin’s approval ratings from 2000 to 2019

Some key domestic problems lie behind Russians’ decreasing satisfaction with Putin. An increase to the retirement age in 2018 has contributed to the noticeable reduction, then, there is the issue of falling real incomes and stagnation in real disposable incomes over the past six years. According to official statistics, the number of people living below the poverty line has increased by 500,000 since 2018. An increase in the value-added tax (VAT) rate last year was also perceived negatively by many Russians.

Finally, Putin is no longer receiving a boost to his ratings from the so-called Crimea effect. Russians rallied around Putin as the country took control of Crimea in the first half of 2014. The polling from that time showed a near 25% increase in Putin’s approval ratings. The Crimea effect is waning, and many citizens would like the government to focus more on the domestic issues raised above.

Issue-specific protests also on the rise

There has been an increase in protests on environmental issues across the country in the past year and they are becoming a more regular feature of the broader political environment in Russia. There have recently been protests in the northern regions of Arkhangelsk and Komi, where about 3,000 people opposed plans to build a waste plant for refuse coming from Moscow. The authorities have been somewhat responsive to these demands. They paused the waste plant and promised to shut down a landfill site outside Moscow by 2020.

However, there is an important difference between these issue-specific protests in which the authorities have offered concessions, and those taking place on the streets of central Moscow. The government is unwilling to offer a compromise to the latter group because conceding on the electoral issue is equivalent to giving away power, which the authorities perceive as a threat to the political status quo.

Political stability probably assured

The recent wave of demonstrations remains unlikely to destabilise the government despite the increase in the number of protesters.

While Putin has certainly suffered a loss of popularity, he continues to have a relatively high net support base across the country. In the recent Levada Center polling at least 54% of Russians noted that they would like to see Putin remain president after 2024, and 43% do not see a viable alternative candidate for the presidency. This is a key problem for the opposition which has not yet found a candidate or party around which it could unite.

The crackdown on the Moscow protests and key opposition leaders is another reason why a major disruption of political stability is unlikely. The authorities have made it clear that they will not tolerate sharing power with the opposition and have denounced the protesters as illegal and violent mobs. The use of violence and pursuit of criminal charges against the protesters increase the cost of participation in the demonstrations for many people.

The number of people willing to take to streets remains marginal relative to the size of the population. The larger attendance figures at the rallies on 20 July and 10 August were most likely due to the fact that the rallies were authorised, thus decreasing the cost of participation. This contrasts with the unauthorised protests, which attracted a maximum of 3,000 people.

The protesters seen at the most recent rallies in Moscow (and at solidarity rallies in St Petersburg) are mostly young, urban citizens who are denouncing the authorities’ use of violence in reaction to the peaceful rallies. Nonetheless, many of them understand that further rallies will likely result in more clampdowns and no concessions from the Kremlin.

Finally, events in the main urban centres of Moscow and St Petersburg rarely act as a model for the rest of country. These cities and their cosmopolitan populations with higher incomes are seen as out of touch with the viewpoints and experiences of most other Russians and, as such, are unlikely to inspire copycat protests around the country.

The looming uncertainty of 2024

Nevertheless, uncertainty surrounding the end of Putin’s current presidential term in 2024 remains. The constitutional rule that Putin circumvented in 2008 to become prime minister for four years before his return to the presidency in 2012 now prevents him from seeking a third consecutive presidential term in 2024. We assess that Putin is unlikely to completely cede power in 2024, even if he does step down from the presidency. It remains unclear what kind of political arrangement will replace his presidency in 2024. What is certain is that any attempt to chip away at the Kremlin’s power, including in the Moscow Duma elections, will be suppressed. However, the current wave of electoral protests is unlikely to prompt the Kremlin to accelerate such succession plans or to unveil them before 2024.

Part of the Big Picture Series, taken from Seerist.

Author:

- Bota Iliyas, Researcher