With voters increasingly disillusioned with established parties, and amid growing public frustration over alleged high-level corruption, Bulgaria’s political landscape has become increasingly fragmented ahead of the 4 April elections. We look at how various election outcomes could impact political and business environments.

- No party looks set to take a majority. Six or seven parties – including newcomers – are likely to win seats in parliament, and an unstable multi-party coalition government is likely to be formed following drawn-out negotiations.

- A centre-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB)-led coalition government would likely face no-confidence votes in parliament and protests on the streets, leading it to pursue more populist policies and resulting in an occasionally unpredictable regulatory environment.

- A centre-left Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP)-led coalition government would likely be an unstable alliance comprising political newcomers, with an anti-corruption focus driving reputational risks for foreign businesses partnering with GERB-linked local companies.

- The new government – regardless of its constituent parties – will come under rising pressure to tackle corruption and implement institutional and judicial reforms or face further protests and instability.

Rejection of the centre

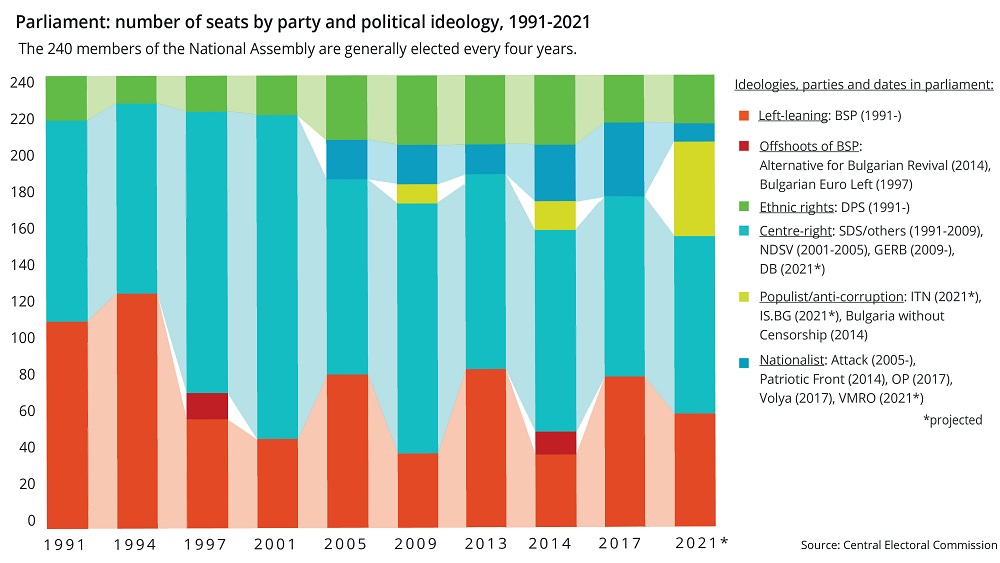

Bulgaria since mid-2020 has seen a wave of protests over allegations of government corruption. Despite some variation in polling numbers, a general trend is clear: since late 2019, GERB and the BSP – the two largest parties, both tarnished by corruption scandals – have been on the decline, while a significant number of voters back populist political newcomers that have an anti-graft focus.

The April parliamentary elections will likely see a much flatter vote distribution than previous polls, and as many as six or seven parties are likely to enter parliament as a result. In addition to GERB and the BSP, the significant contenders are:

- Populist anti-corruption party There Are Such People (ITN), formally founded in February 2020 by popular singer Slavi Trifonov – polling at around 15%.

- Longstanding ethnic minority-rights party Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS) understood to be GERB’s silent partner – polling at around 11%.

- Environmentalist, liberal and centre-right big tent party Democratic Bulgaria (DB) – polling at around 8%.

- Anti-corruption newcomer Stand Up Bulgaria (IS.BG), founded by the national anti-graft ombudsman – polling at around 5%.

- Bulgarian National Movement (VMRO), polling at just below 4% (the threshold needed to enter parliament).

- Populist right-wing party Volya, which supports the current government under a confidence and supply arrangement – polling at around 2%, down from 12% in the 2017 elections.

Barring a major change in voting preferences before election day, GERB (which heads the current ruling coalition) is likely to receive less than 30% of the vote, and the BSP less than 25%. GERB since October 2020 has seen a modest increase in support, likely stemming from positive public perceptions of its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Voters may choose the incumbent over a political unknown at the last minute, but GERB will still struggle to claw back enough votes to reappoint its current coalition – let alone form a government by itself.

The new government is therefore likely to be an unstable coalition formed of three or four parties. Diverging interests, approaches and levels of political experience will result in slow policy implementation, hamper the administration’s ability to respond to emerging challenges, and leave it liable to collapse.

GERB-led government?

GERB as the largest party will have a first attempt at forming a government. It will struggle to find partners and negotiations will be drawn-out. The nationalist and populist parties that currently support GERB’s government – Volya and those that fell under the now-disbanded nationalist alliance United Patriots (OP), including VMRO – have seen their popularity significantly diminish. Current polling suggests that their support would not be enough to secure GERB a majority. The party has few other options. The animosity between GERB and the BSP runs deep, GERB voters would not accept a coalition with the DPS, and DB voters would likely not accept a partnership with GERB.

IS.BG might accept a coalition in exchange for significant judicial reforms. ITN might accept a coalition as a ticket to power. Both may offer a confidence and supply arrangement. Even this might not be enough, and if VMRO secures the 4% threshold to enter parliament, GERB may also need to incorporate the umbrella party in some form. GERB and ITN overlap on some key issues – namely social conservatism and pro-EU stances – but GERB would struggle with some of ITN’s flagship issues, in particular the direct election of the prosecutor general. In any case, any resulting coalition would be unstable, with partners regularly pressing GERB on its corruption record and ties to members of the DPS. GERB would likely drag its feet on the reforms called for by its partners, the BSP would likely mount regular no-confidence votes, and anti-government protests would likely intensify.

This pressure would exacerbate GERB’s growing populist tendencies, leading to an increasingly erratic and unpredictable regulatory approach. The current GERB-led government has demonstrated a tendency to float ideas for legislation in speeches, before rapidly changing course depending on public reaction. For example, in April 2020, it briefly introduced legislation requiring supermarkets to dedicate a portion of their display areas to locally sourced products, before backtracking following an industry and EU backlash.

A different formation

If GERB is unable to form a coalition, the party in second place in the poll – likely the BSP – will attempt to assemble its own. The BSP would not form a coalition with DPS or GERB. A coalition with nationalists would be tenuous, and in any case nationalist parties are unlikely to secure enough votes to play kingmaker. The BSP could attempt to form an anti-corruption coalition, bringing in ITN, IS.BG or potentially DB. However, despite heavily criticising GERB for corruption, the BSP has also been dogged by allegations of graft. The BSP, like GERB, would be likely slow to act on judicial reforms, and any BSP-led coalition would likely be unstable, troubled by inter-party disagreements and recriminations.

Should the BSP succeed in forming a coalition, the new government would need to demonstrate progress on tackling corruption. It would be likely to do so by targeting local businesses with ties to GERB politicians. This would likely come in the form of heightened scrutiny of issues such as environmentalism and contract awards, and potentially stricter regulatory enforcement. Foreign partners working with these local companies would face potential reputational challenges as a result.

Change is coming

Regardless of the exact make-up of the next government, corruption is set to remain a key issue. Growing public consensus that corruption can – and should – be tackled, frustration with the two main parties over their perceived failure to do so, and greater activism and scrutiny from local and international media will ensure the issue remains firmly in the public eye. However, political newcomers campaigning on a platform to eradicate corruption will need to live up to their promises. Should they fail, new challengers will likely be quick to replace them.