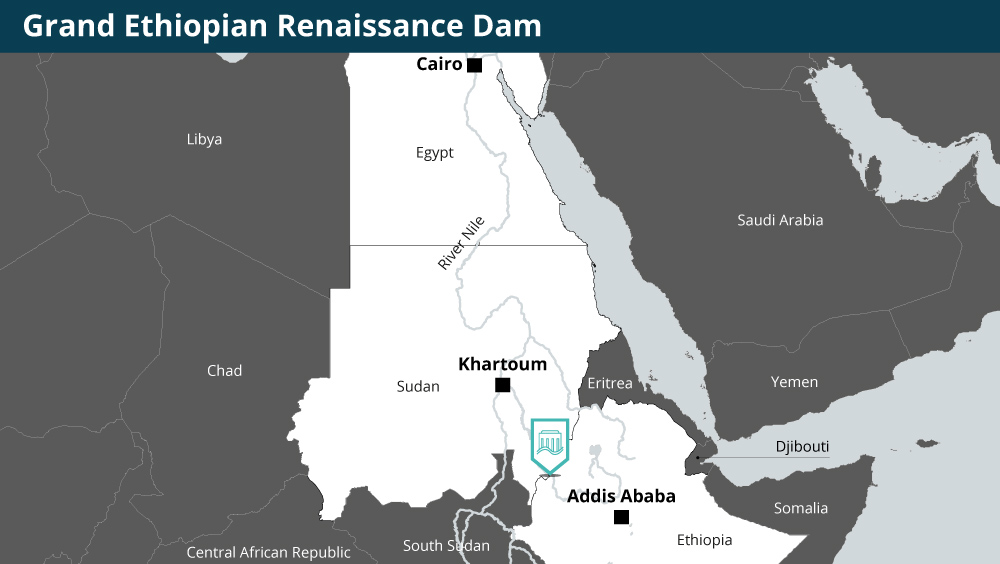

Trilateral negotiations between Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile are expected to continue in the coming month.

- Egypt will continue to strongly resist Ethiopian plans to fill the dam at its preferred speed, for a variety of political, economic and symbolic reasons.

- Meanwhile, Ethiopia will proceed with the filling of the GERD reservoir at its own pace, given the importance of the project to Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s government.

- The absence of a binding agreement guaranteeing Ethiopia will release a specified amount of water downstream to Sudan and Egypt will remain the main source of contention over the GERD.

- International and regional intervention will likely yield positive results only in the one-to-two-year outlook amid the current entrenched positions of Egypt and Ethiopia. However, direct conflict over the GERD remains unlikely.

Aquatic aggravations

Ethiopia on 18 July said it had already reached its target in the second phase of the filling of the GERD’s reservoir despite strong objections from Egypt and Sudan, which are concerned about the potential negative impact of the dam on the volume of water downstream. Egypt had successfully pushed for the issue to be discussed at the UN Security Council on 8 July. However, rather than the diplomatic victory claimed by Egypt, the UN meeting only reaffirmed that the African Union (AU) is the most appropriate mediator in the dispute. Western diplomatic actors including the US and EU have in the past offered their support to the process.

Egypt has been frustrated by the slow pace of the AU-led process. Agreement has remained elusive on key issues, namely the period over which the reservoir will be filled – with Egypt looking for longer than Ethiopia’s suggested five-to-seven years. Egypt and Sudan also want guarantees that Ethiopia will release a specific volume of water once the dam is complete, while Ethiopia does not want to be tied to an exact figure. Talks are likely to resume in the coming month.

Ethiopian escape valve

Fresh from his Prosperity Party (PP)’s election win, Abiy is unlikely to back down on his hardline stance on the GERD, perhaps the only issue on which the PP and opposition groups agree. Built with taxpayer revenues and diaspora contributions, the GERD is a symbol of national pride and self-reliance. For Abiy, this is particularly important at a time when Ethiopia is facing internal criticism and external funding freezes from Western diplomatic actors over the conflict in Tigray regional state. The GERD is a rare catalyst of Ethiopian nationalism in an otherwise fragmented political landscape in which calls for autonomy for ethnic groups often supersede Abiy’s push for a pan-Ethiopian identity. In this context, Ethiopia is unlikely to make significant concessions on the reservoir’s filling in the coming months.

Turning the tap off

Egypt is inherently distrustful of Ethiopia’s claim that the dam will not affect Cairo’s water supply from the Nile. Moreover, water has both real and symbolic importance in Egypt, where the Nile feeds much of the country's agriculture industry and other sectors. A reduction in water from the Nile would therefore have very real consequences for political stability, and by extension President Abdul Fatah al-Sisi’s political position.

As in Ethiopia, nationalism is a key driver of Egypt’s stance in the negotiations. Even if a deal is agreed in which Ethiopia guarantees Egypt a sufficient supply of water, the public would take a dim view of the fact that Ethiopia has any form of direct or indirect control over Egypt’s water. The blame for this would rest squarely on Sisi’s shoulders. Having in recent years portrayed himself as a strongman in various regional initiatives, Sisi’s position in the GERD negotiations will be largely defined by the knowledge that his domestic and regional position will be undermined if Ethiopia does not acquiesce to his demands.

Dammed diplomacy?

The AU therefore faces a challenging task in trying to find common ground between Egypt and Ethiopia. As a regional body, the AU’s successful resolution of the GERD dispute would boost its credibility as the main arbiter in African affairs on a continent where non-African intervention has historically been more common. Nonetheless, several other actors will be important players in the process.

First, Sudan – caught in the middle physically and figuratively. Although it has most recently sided with Egypt amid tensions with Ethiopia over their shared border, Sudan has always quietly supported the GERD, given its potential impact in regulating seasonal flooding and boosting access to electricity in Sudan. Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok is also respected by international actors, Ethiopia and Egypt, and is likely to play a pivotal role in helping calm heads to prevail.

By contrast, the limits of Western intervention – by the UN, US, EU and even the World Bank – appear to have been reached. Abiy’s government deeply resents their criticism of the Tigray conflict and is unlikely to accept their involvement. The threat of more funding withdrawals by Western actors – which have already paused selected programmes over the conflict in Tigray – could further pressure Ethiopia. However, this would be likely to result in Ethiopia shifting its ideological support and appeals for funding towards China and Russia. Many Western governments would be keen to avoid such an outcome amid continued geopolitical tensions between Western actors and China and Russia.

The dark horse here is potentially the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which remains on friendly terms with all parties. The UAE was instrumental in brokering the landmark 2018 peace agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea, has been a key source of financing during Sudan’s turbulent transition, and in recent years has been a significant source of funding and investment in Egypt. Given its strong relationships with and financial leverage over all actors, the UAE could also play a positive role in mediation, as suggested by Sudan in March. This would be preferable to Egypt’s suggestion that the Arab League mediate, given that it has overtly sided with Egypt on the issue.

Water war?

Regardless of the choice of negotiators, talks on the GERD are likely to remain slow and piecemeal. Increasingly belligerent rhetoric is likely from both sides over the coming months as leaders attempt to project an image of strength to their domestic audiences.

Nonetheless, we maintain that a direct conflict is unlikely. In addition to the cost and logistical issues that such a confrontation would entail, international pressure on all parties to avoid such an outcome is too strong. Egypt – the most likely belligerent, and most bellicose in its rhetoric – is unlikely to launch a pre-emptive overt attack on the dam. Most of Egypt’s media campaigns and political statements on the issue are primarily designed to divert blame from Sisi for preventing the dam from being built and filled, and portray Ethiopia as the cause of Cairo’s future water-related issues. However, Egypt will retain an interest in undermining political stability in Ethiopia more generally, and will seek to do so through information campaigns and covert funding to opposition groups.

Nonetheless, ultimately Egypt and Sudan cannot escape the reality that the dam exists and will have a bearing on their water supply. As a result, some form of agreement is likely to be reached in the coming years, even if this is a bitter pill for Egypt to swallow.