This article is based on content originally published on our partner platform Seerist, the augmented analytics solution for threat and risk intelligence professionals.

On 28 August, the UN Security Council (UNSC) passed resolution 2749. The resolution renews the mandate of the United Nations Interim Force for Lebanon (UNIFIL) – the UN’s peacekeeping force in southern Lebanon – until 31 August 2025.

What will be the impact of UNIFIL’s presence along the UN-demarcated de-facto border between Lebanon and Israel, known as the Blue Line, over the coming years?

- The mandate renewal will not impact ongoing cross-border fighting between the Lebanese Shia movement Hizbullah and the Israel Defence Forces (IDF), which has been characterised by near-daily exchanges of fire since October 2023.

- Although Israel and Lebanon could credibly begin negotiations through the US to resolve the border dispute over the coming year, it is unlikely that a conclusive demarcation deal will be reached as negotiating stances remain far apart.

- Businesses with operations in southern Lebanon and northern Israel will continue to be exposed to incidental security threats due to cross- border exchanges of fire over the coming year.

Mandate renewal

Although all 15 members of the UNSC voted in favour of renewing UNIFIL’s mandate under the framework of resolution 1701 – which served as a ceasefire agreement ending a 34-day war between Hizbullah and Israel in August 2006 – a few points in the mandate renewal encountered disagreement. The US representative to the UNSC, Robert Wood, expressed his disappointment that several members of the UNSC blocked attempts to openly condemn Hizbullah’s attacks on Israel. Meanwhile, Israel – which is not currently a member of the UNSC but party to the resolution – advocated for shortening the mandate of the peacekeeping force from one year to six months. France and other members of the council disagreed with Israel’s suggestion.

Referencing ongoing exchanges of cross-border fire between Hizbullah and Israel, the UNSC called on the parties to the resolution to de-escalate tension and restore security and stability. Members of the council, including France, South Korea and China, reiterated this point individually.

Under the framework of UNSC resolution 1701, UNIFIL’s main tasks include monitoring compliance with the provisions of the ceasefire between Lebanon and Israel, supporting the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) in its incremental deployment in southern Lebanon, and providing humanitarian support for civilians.

Limited impact

The extension of UNIFIL’s mandate will not impact the nature of Hizbullah and Israel’s current or future tit-for-tat exchanges of fire. Since 2006, both Israel and Hizbullah have violated the terms of UNSC resolution 1701 and neither party has been held accountable.

Over the past two decades, UNIFIL and the Office of the UN Special Coordinator for Lebanon (UNSCOL) have compiled 55 reports for the UN secretary general documenting violations of resolution 1701, including cross-border rocket fire by Hizbullah and Israeli airstrikes on Lebanon.

However, UNIFIL’s mandate falls under Chapter VI of the UN Charter, which largely restricts its use of force to self-defence. This means that UNIFIL cannot effectively enforce the provisions of resolution 1701, such as confronting the presence of armed groups, by using military force. Since 2006, some Western countries – primarily the US and Israel – motivated by concerns over Hizbullah’s growing influence and presence along the Blue Line, have lobbied to change UNIFIL mandate to Chapter VII. This change would allow the peacekeeping force to use military force to confront violations of 1701.

If the mandate remains under Chapter VI, UNIFIL’s effectiveness and impact will remain largely limited to monitoring and reporting violations, and occasionally acting as a quasi-mediator for de-escalating tensions between Lebanon and Israel.

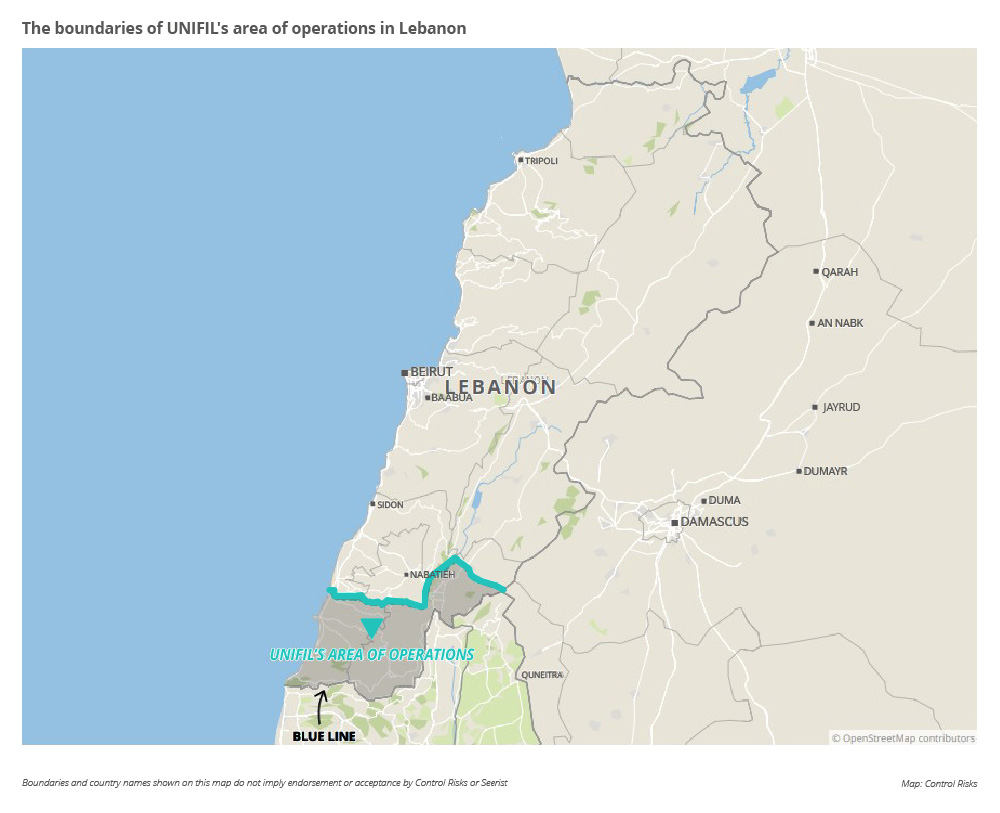

The boundaries of UNIFIL’s area of operations in Lebanon

A complex mandate to fulfill

UNIFIL’s ability to fulfill its, albeit limited, mandate has grown increasingly complex in recent years.

One of the force’s key concerns and justifications for why it has been unable to counter the presence of Hizbullah and help implement 1701 has been its increasingly limited ability to travel freely through its 1060 sq km area of operation between the Litani river and the Blue Line. UNIFIL must coordinate its routes and patrols with the LAF, which the LAF – driven mainly by politically-connected Hizbullah – has progressively limited. The LAF also tightly coordinates UNIFIL movements due to concerns within the government over the perceived violation of sovereignty that UNIFIL’s operations represent for some political figures.

To increase the effectiveness of UNIFIL operations, the language of its mandate (UNSC Resolution 2539) was modestly altered in 2020 under the administration of former US President Donald Trump. The resolution asked the Lebanese authorities to ensure that peacekeepers be granted access to locations to facilitate swift investigations of reported violations of 1701. These modifications proved largely cosmetic. UNIFIL’s continued inability to patrol freely was evident when residents in Shaqra village attacked one of the force’s vehicles in December 2021.

Volatility will persist

The security environment along the Blue Line will remain volatile over the coming year. The challenge of reaching a ceasefire between Hizbullah and the IDF is one among many. Others include: Hizbullah’s armed presence in southern Lebanon along the Blue Line, the absence of an officially demarcated border, the lack of agreement over disputed areas such as Shebaa farms and Israel’s continued violations of Lebanon’s airspace. All will remain critical issues, driving a heightened level of insecurity in northern Israel and southern Lebanon.

Western countries, particularly the US, have presented proposals aimed at addressing these points and brokering a ceasefire deal.Since January, senior US envoy Amos Hochstein has put forward proposals that could act as a ceasefire agreement and serve as an entry point to negotiating a demarcation of the land border. The terms of the proposals remain confidential; however, according to domestic and international reports, the proposals aim to establish a Hizbullah-free buffer zone along the Blue Line with the deployment of LAF soldiers. Meanwhile, the IDF would suspend its violations of Lebanon’s airspace. In October 2022, Hochstein brokered an agreement between Lebanon and Israel to demarcate the states’ maritime boundary following years of stalemate.

In June, Media agencies reported that Hizbullah had given its Shia political ally, the Amal Movement, the greenlight to kickstart negotiations with Israel through the US after a ceasefire is reached in Gaza. Although such discussions are likely to commence over the coming year, they are unlikely to conclude successfully, prolonging the threat of cross-border fighting between Hizbullah and Israel. Hizbullah is very unlikely to give up on its presence in southern Lebanon – south of the Litani river – and agree to disarm, two points laid out in UNSC resolution 1701 that Israel has continuously insisted should be part of any long-term ceasefire deal.

Outlook

Foreign entities and personnel operating in southern Lebanon and northern Israel will continue to face incidental security threats if located in the vicinity of attacks by either Hizbullah or the IDF. Organisations located in areas about 20km (12.4 miles) north and south of the Blue Line, such as Kfar Kila and Kfar Chouba in Lebanon, and Shtula and Margilot in Israel, will be the most exposed to attacks.

Additionally, entities present in Hizbullah strongholds, such as Bekaa governorate and close to Lebanon’s border with Syria, are likely to be exposed to incidental security threats from Israeli attacks. Both Hizbullah and the IDF will primarily focus on targeting military and critical assets to undermine each other’s capability.